December 13, 2015 - 19:42

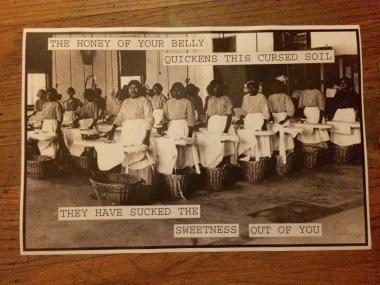

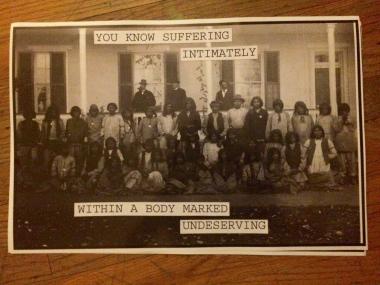

I began this project believing that I would do a concrete, and very explicit representation of the connections between Native American boarding schools and prison. There were many similarities between the two that I could find, especially after conducting deeper research. I planned on showing these connections through an easily understood guide, a complex visual that would trace these connections through time. At one point I thought I would expand it into a timeline. But then I ended up changing everything in the last two weeks of working on the project, doing a complete 180, deciding to focus on the “art” part of the Arts of Resistance. For my project, I decided to choose three photographs of the Carlile Boarding School that I felt showcased the underlying nature of the cruelty that happened in these schools. The photographs were clearly posed, and there is no true photographic evidence of the emotional and physical violence inflicted. In my project, I displayed poetry alongside (or on top of) the photographs in an effort to expose the events that transpired more secretly, poetry that also could be applied to, and reflected on, the prison industrial complex today.

I knew that I was toeing a thin line with this project. I did not want to give impose a damage-based narrative onto those who had their agency taken away from them. But at the same time, I wanted to make people feel something from looking at my piece, to begin to understand the trauma that comes from forced assimilation and how this could be compared to the current prison system. For this reason, I decided to use my own words for the juxtaposition; I did not say that this was poetry written by me, mainly so that the viewer could freely reinterpret it. In my caption I stated: “…I have placed photographs of the Indian Schools, which were a violent assimilatory tactic by the American government, alongside poetry about the contemporary incarceration system, which is grounded in racial control.” I hoped that it would be evident from the caption that I mean to show that prisons, themselves, are also a “violent assimilatory tactic”.

I think I did accomplish something in that direction. A lot of folks came to me later to learn more about the project, or to tell me that my questions had made them think about the emotional toll of the PIC. I believe that people a basis in envisioning history helps them understand the emotionality of the present. A lot of times, I chose not to answer people’s questions, saying that these were highly complex and require a level of self-reflection that each person must come to on their own; they are things that I, even after this whole semester of reflection, have not been able to fully answer.

I learned about the complex experiences of Indians in these schools, as well as Indians in prison today. Just as some Indians actually benefited from learning trades in these schools and were able to be taught by Indian educators at the Carlile Boarding school, some Indians today are given opportunities to keep in touch with their culture and religion through programs run in prisons in Nebraska and South Dakota. But while experiences were and remain complex, the vast majority of them were traumatizing and negative, which is what I hoped to show.

I also learned so much about my own abilities. It has been a long time since I have delved into the creative within academia, and this project opened the door to that. Writing that poetry was such an experience; I did it when I was alone and found myself deeply influenced by the works two of my favorite poetesses of color, Warsan Shire and Rupi Kaur. I was more proud of that poetry than I could have been of a ten-page paper, because it required stretching myself in a way that I have not done before. I feel like I can do so much more in that direction, and it has inspired me to want to take poetry and creative writing courses while I can.