December 13, 2015 - 14:44

As soon as I decided to focus my creative project on the transgender incarcerated community, I knew that I wanted to utilize the physical form of the DSM in some way. I first began to think about the book and its impact as a freshman, in the introductory Gender & Sexuality Studies course. I had a personal connection to the lawyer working to support Michelle Kosilek (an incarcerated transgender woman) in her court battle for gender affirmation surgery covered by prison healthcare, and I wrote my final paper for the course on the use of diagnosis and the DSM-V in her case; I argued that although the employment of the book in its authority and official nature was inarguably helpful for her particular case, its existence and the resulting pathologization of the transgender identity was ultimately detrimental to the transgender community. My thinking on this subject was only complicated when I participated in the Identity Matters 360, using the combination of courses in Critical Feminist Studies and Disability Studies to unpack the intersections between transgender and disabled identities. What I discovered through reading such activists and theorists as Eli Clare (someone who identifies as both transgender and disabled) was that there is something implicitly ableist in the claim that transgender people should push away all diagnosis in the fight for medical care. In doing so, one insists that having a mental illness is inherently a bad thing—and while the DSM-IV’s diagnosis of Gender Identity Disorder is inarguably problematic (as it pathologizes the transgender identity itself), the DSM-V’s transition into the diagnosis of Gender Dysphoria (naming the distress caused by a gender and physical sex that do not align) can at least serve as a useful tool in the path toward hormone treatment or affirmation surgery. “Diagnosis” is a complicated idea within the disabled community as well, because despite its usefulness, it must generalize and categorize human beings whose “conditions” exist on a complex spectrum. However, it is inarguably essential as far as medical treatment goes, at least as the health care system currently stands.

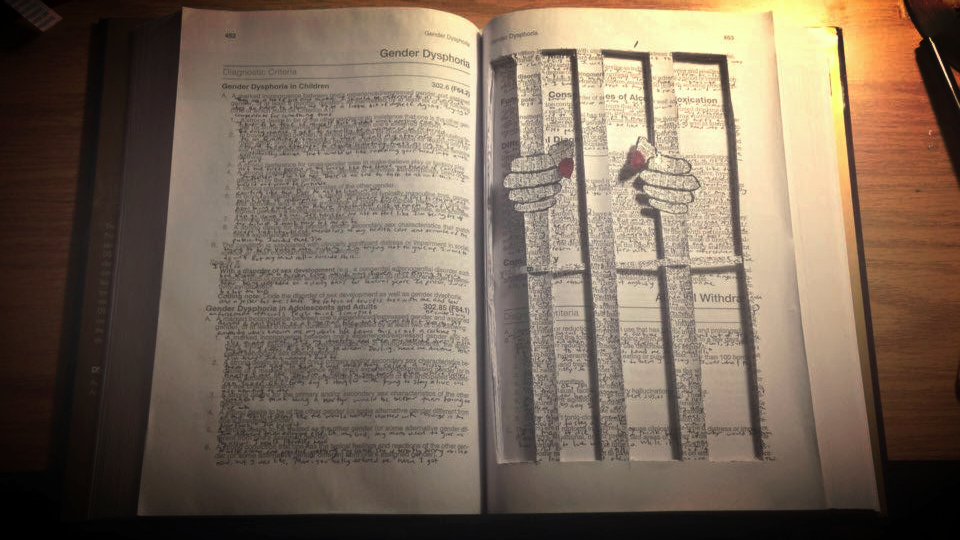

As I looked into more cases of transgender incarcerated people who were going to court and seeking coverage for treatment through the prison healthcare system, the use of the DSM was a constant—frequently, the only thing working in their favor was the diagnosis by a mental health professional who was an expert and authority figure trusted by the court. I wanted to highlight the complexity of the DSM in my artistic presentation—to show that while it and the concept of diagnosis can both be imprisoning, the book itself is also a tool and is unarguably useful. I also noted the very impersonal nature of the text, which does not serve to present the real lived experiences of people who fit the criteria for Gender Dysphoria. To combat this, I collected the words of transgender incarcerated people from news stories and blog posts, writing them between the lines of the book to interfere in its presumed authority. As I went through these news stories, I noticed many trends in terms of exactly what words were included. The words of these incarcerated transgender people seeking treatment were overwhelmingly negative (absolutely reasonable, based on the inhuman conditions they were facing, though I did find some positive/hopeful remarks that seemed to indicate there was much of the story being left out by these sensationalizing media sources), and when they spoke to anything beyond their need for surgery itself, it was to apologize deeply for the “criminal acts” that they regretted more than anything. It was interesting to me that the media found it necessary to present these statements—as if the only way to rally public support for the human right of proper health care was to de-criminalize them (“human” and “criminal” were too identities that the public could simply not simultaneously hold for someone they did not personally know).

Because I already had considerable background knowledge about the DSM and its use in providing treatment for transgender people (incarcerated and otherwise), most of what I gained from this project came from the reading of individual stories, and from analyzing how they were presented by mainstream media. I was left with many questions, two of which I presented on my placard:

What could the world look like if our right to medical care was determined by our humanity, rather than our lack of criminality? Why must we first forgive in order to grant dignity?