April 5, 2016 - 00:09

“The capacity to do research, in this broad sense, is also tied to what I have recently called ‘the capacity to aspire’ [. . .], the social and cultural capacity to plan, hope, desire, and achieve socially valuable goals. The uneven distribution of this capacity is both a symptom and a measure of poverty, and it is a form of maldistribution that can be changed by policy and politics” (Appadurai 176-77)

Often, when people become parents of children with intellectual or developmental disabilities, they feel that their dreams—what they have always wanted for their child—have been crushed. Surely their children can have no future—and because people with intellectual disabilities face infantilization throughout their lives, many live in perpetual states of futurelessness. After high school, education ends for most adults with intellectual disabilities. Expanding the horizons of their knowledge is simply not considered valuable, and many are considered “unteachable.”

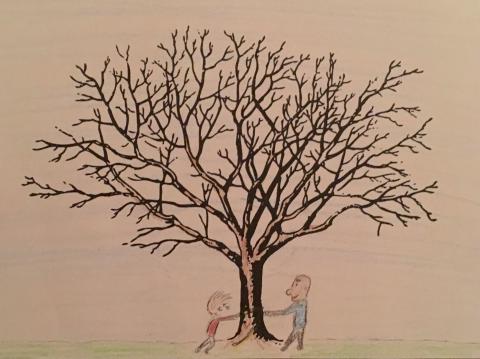

Last week, we traveled to Haverford’s campus with artists from the center to do some research. Since we were using white oak wood to build our boxes, we decided to learn more about the white oak trees that are so common on the campus. We measured them to determine their age and height, and drew them while seeing them in person. In my field notes, I expressed the strong feelings of connection that I felt in this moment. The center was creating a space where adults could constantly exercise their right to aspire—by offering them the chance to learn through and about an engaging artistic project.