October 9, 2014 - 03:12

Beverly McIver is a woman whose life has taken her on a non-normative path. She is an artist who was “thrust” into the role of taking care of her sister who has developmental disabilities. We can see the journey that she has taken with her sister, Renee, and how they have coped with it through Beverly’s portraits. Beverly invites the viewer to peek into her life, and shows them how a ‘non-normative’ life can be fulfilling.

Part I: Queering Time

The idea of queering time comes from the desire to challenge what we see as ‘normative.’ In a normative life path, one might go to college, get a job, get married, and have kids. We start this progression at a young age. We want our kids to do well in elementary school so that they can do well in middle school, and then high school. It is essential to do well in high school in order to get into a ‘good’ college, whether that means a college with a good name or education. Because only with your diploma from college can you get a good, stable job. And with the money that you get from your job you will use to provide financial stability for your spouse and children, so that when you retire in your 60s or 70s your family will be secure. Ideally you would accomplish all of this without too much help from others. Along with financial security, finding independence is key. Receiving a substantial amount of help from others is a sign of failure (Halberstam 1).

'Calendar Girl'

It is assumed by many that people with developmental disabilities will not follow this path. It is uncommon for people with developmental disabilities to go away to college because it is thought that they cannot be independent. The highest level of education achieved might be a life skills class, where they learn how to pay bills and go grocery shopping (Green). Does this cause some self-doubt or self-conscienceless? In ‘Calendar Girl’ we see Renee with a backdrop of many calendar months. It seems like all those months, possibly years, have passed. In this portrait Renee looks disgruntled. She is looking down and to the side. Her mouth is frowning, and the shading on her forehead slightly resembles the furrowing of eyebrows. Despite the cheery disposition of her yellow top, Renee is unmistakably upset. Is it because of all the things she didn’t do but ‘should’ have done?

'Renee Sleeping at Macys'

Beverly has had her path altered through Renee. Not many people are expected to ‘raise,’ or take care of an older sibling after their parent dies. That step is not on the normative life path because it is not the same as supporting a spouse and kids. If they are not your own offspring you are not expected to take care of them. Beverly loses some sort of ‘independence’ by taking over the care of Renee (Green). We can see in “Renee Sleeping at Macys’s” how disruptive Renee’s presence might be. Renee’s face is distorted in a way that shows she did not fall asleep peacefully. She was probably very exhausted, and Beverly was probably exhausted too. I could imagine the frustration felt by Beverly before and after the point of time of this portrait. Beverly looks very tired in her self-portraits. In her self portraits ‘Portrait for Horace’ and ‘Web Size Turning 50’ Beverly is looking down with her eyes closed. These gazes invoke feelings of contemplation. What is she thinking about? She could be thinking about time, or her relationship with her sister, or just resting. In ‘Portrait for Horace’ we again see a calendar as a background, which very much reflects time passing. However, we also see a circled date. What was supposed to happen on the 25th? The date has already passed, as suggested by the crossed off dates after it. Did an event that was going to happen on that day not happen? Is Beverly still waiting for that event to occur?

'Portrait for Horace'

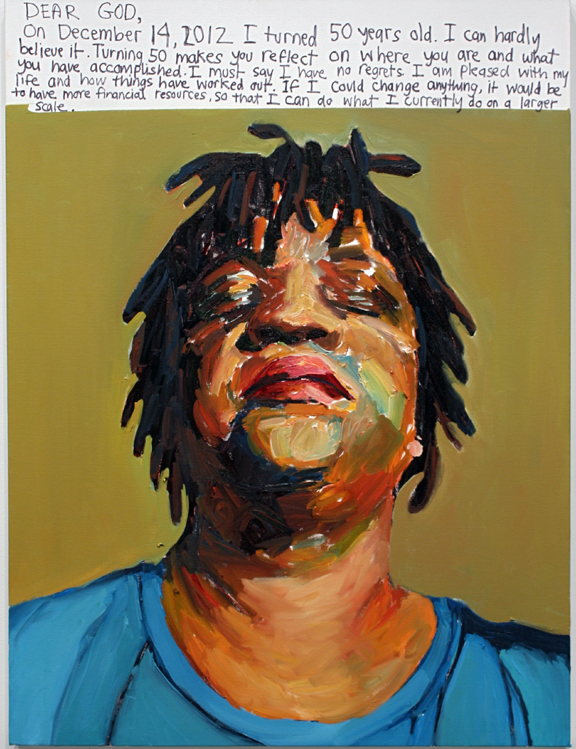

'Web Size Turning 50'

What is the consequence of deviating from the normative path? Theoretically unhappiness and un-fulfillment. However, Renee and Beverly show no signs of that. While there are portraits of them that show them at more unhappy light, there are also portraits of them with looks of bliss. As with all lives, there are ups and downs. In ‘Renee Diptych’ we see a lovely portrait of Renee smiling. She is wearing purple, one of her favorite colors. She is looking straight at the viewer, her gaze unwavering. She looks very friendly, and it looks like she is meeting us for the first time, ready to say “hi.” In ‘Turning 50’ we see Beverly with a serene look on her face. She is wearing a birthday hat, an unusual accessory for a 50th birthday, which almost reverts her back to childhood. She certainly looks younger than the other portrait of her “turning 50.” With youth comes less stress. Perhaps she is imagining herself at a stage in her life before she had to take care of her sister. In ‘Web Size turning 50’ Beverly included a letter written to God about her birthday. I am assuming Beverly wrote it from what I know about her age during an interview she did in 2012. The letter addresses the reflection that Beverly has done on her life thus far. In this letter Beverly wrote that after reflecting everything that went on in her life, she has no regrets. Despite leading a non-normative life, Beverly and Renee are still happy.

'Turning 50'

'Renee Diptych'

Part II: Gaze

In our western, American culture, it is considered rude to stare. Depending on which part of the US you are in you might not even be expected to look at someone when you are walking down the street. Otherwise, there might be a certain amount of seconds that is considered polite before you have to move your gaze. But in art, the gaze of the viewer is required. Rosemarie Garland-Thomson wrote, “Photos are made to be looked at” (Garland-Thomson 58). The same goes for other types of visual media, such as painted portraits.

Beverly invites people to stare at her portraits. I was captivated when I had my first look. The colors and the way they are arranged on the canvas make me want to look at them again and again. I imagine with the way that Beverly uses the oil paint the effect is so much stronger in person. The thick brush strokes draws the eyes to the face, the most prominent part of the portrait. In Beverly’s portraits the face holds the most emotion. Each brush stroke contorts the face in a way that a realistic portrait couldn’t. Therefore we can see ‘more’ of the subject than you would be able to when getting a polite glance at them in person.

'Eyes Wide Open'

Beverly’s tendency to have the subject have closed eyes or an off-centered gaze also invites the viewer to stare. It is so much easier to look at the portraits when you are not looking directly into the eyes of the subject. Without a direct gaze there is further removal from the viewer and the subject. In ‘Eyes Wide Open’ we can see the difference clearly. On the left pane Beverly’s eyes are closed, and it appears as if she is sleeping. We can easily look at her face and try to figure out what she is thinking. On the other hand, her face on the right pane is more challenging to look at. Unlike the other portraits that Beverly has done, I have the urge to look away. My eyes always drift to the left pane. If all of her portraits were done with such intent stares I would not want to look at them as closely as I so with indirect stares. And I wouldn’t be able to focus on all the other things that are going on in the photo. I would miss all the emotion in the face that was highlighted by the colors in the skin. If I am not looking into the eyes of the subject, I do not have to worry about what she is thinking of me. Is she judging me for staring? Am I seeing what she wants me to see? All these things I don’t have to consider when their eyes are closed.

It is so important that we are able to stare at Beverly’s portraits. She gives us the opportunity to see people with developmental disabilities. And instead of trying to show how she and Renee are ‘just like everybody else,’ Beverly highlights the differences in her and Renee’s life. She does so in a way that makes it clear that even with differences her life is okay. This creates visibility for people with disabilities that hasn’t around before. People look at art. If they don’t see a story told through painting, they might never know that story. Beverly shows Renee’s life and personality through her portraits, recognizing that Renee, though intellectually disabled, has a life and a personality. And this story will be documented permanently. Long after Renee and Beverly pass there will be a legacy of them that will be alive in the world. People will be able to get to know them and their story. A path will have been made for the Renees and Beverlys in the future, who might feel self-conscious of the non-normative path that they took in life.

Works Cited

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. "The Politics of Staring: Visual Rhetorics of Disability in Popular Photography." Disability Studies: Enabling the Humanities. New York: Modern Language Association of America, 2002. N. pag. Print.

Green, Penelope. "Painting on a New Canvas." The New York Times. The New York Times, 08 Feb. 2012. Web. 09 Oct. 2014.

Halberstam, Judith. In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. New York: New York UP, 2005. Print.

McIver, Beverly. Calendar Girl. Beverly McIver. Web. 9 October 2014.

McIver, Beverly. Eyes Wide Open. Beverly McIver. Web. 9 October 2014.

McIver, Beverly. Portrait for Horace. Beverly McIver. Web. 9 October 2014.

McIver, Beverly. Renee Asleep at Macys. Beverly McIver. Web. 9 October 2014.

McIver, Beverly. Renee Diptych. Beverly McIver. Web. 9 October 2014.

McIver, Beverly. Turning 50. Beverly McIver. Web. 9 October 2014.

McIver, Beverly. Web Size Turning 50. Beverly McIver. Web. 9 October 2014.