September 28, 2014 - 23:59

Three weeks ago, two Bryn Mawr students hung a Confederate flag in the hallway outside their room. The incident caused major uproar on campus; students felt hurt by the display of racism, unheard when their complaints were made to the students, and unsupported by administrators at the outset of the incident. After the flag was removed from the hallway and re-hung in one of the students’ rooms, some interesting pictures began to circulate. Hanging outside of the building from one of the student’s room was a Pride flag, and hanging visibly within the window of the other room was the Confederate flag.

(photo credit to khinchey)

I was not the only one to express surprise and confusion surrounding this pairing. It seemed incongruous for the pride flag to hang next to the Confederate flag for several reasons. First, it seemed wrong because of the history of the Confederate flag’s use by the KKK against the LGBTQ community. Second, it was confusing because of my assumption that progressive ideology in one sphere (LGBTQ pride, for example) translated to progressive ideology in others. This picture proved that is not the case.

These students aren’t the only or the first people to hold equality and justice for one group in the same hand as oppression of another; white feminists oppressing women of color, and the state of Israel oppressing asylum seekers are just two examples. As Anne Dalke has said, “There is a non-transferability of [understandings of] marginalization.” I was left with the question: Why are there marginalized people who are not accepting of or who act in oppressive ways towards other marginalized identities? What allows someone to fight against oppression in one realm and not see it in another? In trying to understand this phenomenon I dig into the past to and look to M. Carey Thomas.

I. M. Carey Thomas: Feminist, White Supremacist

M. Carey Thomas was Bryn Mawr’s third president and one of the most influential voices in the founding and early development of the college (Horowitz, 1984 and Horowitz, 1994). Since youth, she felt strongly that women should have equal access to education. At 14 years old, she wrote in her journal:

“How unjust-how a narrow-minded-how utterly uncomprehensible [sic] to deny that women ought to be educated and worse than all to deny that they have equal powers of mind. If I ever live and grow up my one aim and consentrated [sic] purpose shall be and is to show that a woman can learn can reason can compete with men…” (1871).

And indeed she did grow up to work towards that purpose. In 1877, she entered Cornell and “thrived” (Horowitz, 1984). After graduation, she struggled to obtain a graduate degree, but succeeded and then gained a professorship and deanship at Bryn Mawr College under the James Rhoads’ presidency. She took on the task of informing Bryn Mawr’s practices based on study of several other women’s colleges. In 1894, Thomas took on the presidency (1984). At the turn of the century, Thomas published on the topic of women’s education, arguing staunchly that education and post-college opportunities should be equal for men and women. She wrote: “we cannot think that men students of law or medicine or architecture, for example, should be college-bred, while women students of law, medicine, or architecture should not” (1901).

In spite of this progressive stance, Thomas was also incredibly racist and classist. This wasn’t a learned attitude from her family, but instead a self-developed belief. In discussing how Thomas differed from her mother, biographer Helen Horowitz writes,

“Although daughter was impelled by some of the same enthusiasm, energy, and sense of the world’s wrongs that drew her mother to reform, in critical ways she diverged. As she dedicated her career to offering [educational opportunities] to women […] Carey Thomas did not mean all women.” (1994)

And in fact, Horowitz writes that as a young adult, Thomas was ashamed that her mother opened their family home to “inferiors” (1994). In the 1910s as Thomas travelled increasingly, she also calcified her racist views – looking down on people of color whom she encountered around the world. In 1915, she visited Japan and met with women who had graduated from Bryn Mawr. In spite of her reportedly respectful attitude during the trip, she wrote home that the Japanese people were, “orientals and savages and that in spite of their wonderfully intelligent government they can never compete with us. They are radically unintelligent, I feel sure,” (in Horowitz, 1994). That she could say this in spite of the knowledge that these women were Bryn Mawr graduates highlights how deeply ingrained her sense of racial superiority was. In 1916, she gave her first public address sharing these views. In her address she says, “The pure Negroes of Africa, the Indians, the Eskimo, the South Seas Islanders, the Turks [… had] never yet in the history of the world manifested any continuous mental activity nor even any continuous power of organized government” (in Horowitz, 1994). Ironically, this was nearly the same thing men had said about women in their argument against the equal education of men and women, and yet Thomas was able to hold in the same hand her racist and feminist views.

I believe that Thomas developed a rhetoric and belief in elitism as a way of protecting her personal gains. Thomas was a white and upper class woman who was raised with enormous additional privilege – parents supporting her education and independence (Horowitz, 1984). Though she had several very close and long-term relations with women, there is no evidence that Thomas faced outward discrimination based on her sexuality (Horowitz, 1994). Thomas’ struggle for equity in education was one of her only major identity struggles, and a successful one at that. She hierarchized identities placing her own at the forefront. In protecting her own social position, she oppressed others.

II. Minnie Bruce Pratt: an Intersectional Social Justice Lens

Minnie Bruce Pratt is a white lesbian feminist and activist who came from a relatively similar background to M. Carey Thomas – both were upper/upper-middle class, both were white, both were highly educated, both were non-heterosexual (Rapp, 2004 and Horowitz, 1994).

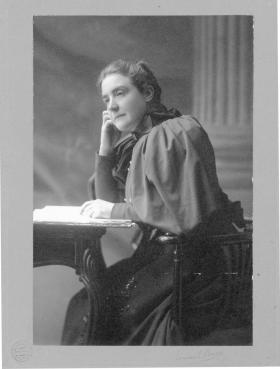

(Picture of Pratt) (Picture of Thomas)

Unlike Thomas, however, Pratt has spent her life working on intersectional social justice combining anti-racist activism with feminism, the fight for lgbtq rights, and more (Rapp, 2004). Pratt provides a lens from which we may understand Thomas’ seemingly incongruous views. She questions where her own drive to make change comes from, “if we are women who, by skin color, ethnicity, birth culture, are in a position of material advantage where we gain at the expense of others, of other women? […]” (1984). What drives someone to push past the force of stasis? What challenges us to step outside of our comfort zones? In thinking about understanding her own privilege, Pratt writes:

“I didn’t understand how much I was still inside the restrictions of my culture in my vision of how the world could be…

…Yet, if we are women who have gained privilege by our white skin or our Christian culture, but who are trying to free ourselves as women in a more complex way, we can experience this change as loss. […] Our fear of the losses can keep us from changing.” (1984).

This idea – that coming to terms with one’s privilege involves a sense of loss or is experienced as loss is a vulnerable-making idea and a vulnerable-making process and one I would argue Thomas was not willing to even approach after her hard won victories in education.

III. Thresholds and Transferability

That sense of loss and vulnerability is one I thought deeply about when considering my own process of understanding my privilege. I didn’t call it loss in that writing; I called it a threshold concept. In thinking about thresholds with Professor Carola Hein, she and I decided “Thresholds are transformative moments of learning that are irreversible, integrative, and discursive; they are moments when deep and often difficult learning occurs.” (Hein and Abbot, 2013) Perhaps for Thomas, coming to terms with her privilege was a threshold she was unable to cross. It takes a certain amount of guiding and mentorship to move past denial of this new information (the existence of privilege, for example) and into the sense of loss that comes with acceptance. And it is important to note that Thomas was most loudly expressing her racism at the same time she was working to protect her inheritance from her deceased friend and lover (Horowitz 1994). I would argue she couldn’t come close to experiencing the sense of loss that come from understanding privilege if she was working to avoid a sense of loss in other spheres of her life.

Let’s return to the present and to the students who were responsible for the pairing of the Confederate and Gay pride flags. The students’ progressive stance on one topic cannot be assumed to transfer to progressive understandings in other spaces. While students including myself were shocked and frustrated by the racism of the action itself as well as their defensive response, we can – perhaps – understand their slowness in apologizing and their seeming disregard for the hurt they caused other students by remembering that understanding privilege is a threshold for learning. It requires a level of loss and vulnerability, and needs guiding and support to go past that.

Works Cited:

Abbot, S. (2013, June 15). Understanding Privilege. Retrieved September 28, 2014, from http://teachingandlearningtogether.blogs.brynmawr.edu/archived-issues/ninth-issue-sprin-2013/understanding-privilege

Hein, C., & Abbot, S. (2013, June 15). Facilitating Threshold Moments in Innovative 360º Course Clusters. Retrieved September 28, 2014, from http://teachingandlearningtogether.blogs.brynmawr.edu/archived-issues/ninth-issue-sprin-2013/facilitating-threshold-moments-in-innovative-360-course-clusters

Horowitz, H. L. (1984). A Certain style of "Quaker lady" dress. In Alma mater: Design and experience in the women's colleges from their nineteenth-century beginnings to the 1930s (pp. 105-116). New York: Knopf.

Horowitz, H. L. (1994). The power and passion of M. Carey Thomas. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Margalit, R. (2014, January 8). Israel’s African Asylum Seekers Go on Strike - The New Yorker. Retrieved September 28, 2014, from http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/israels-african-asylum-seekers-go-on-strike

Pratt, M. B. (1984). Identity: Skin, Blood, Heart. In E. Bulkin & B. Smith (Authors), Yours in struggle: Three feminist perspectives on anti-Semitism and racism. Brooklyn, NY: Long Haul Press.

Rapp, L. (2004). GLBTQ Literature: Pratt, Minnie Bruce. Retrieved September 28, 2014, from http://www.glbtq.com/literature/pratt_mb.html

Thomas, M. C. (1871). Excerpt from M. Carey Thomas journal, February 26, 1871. Retrieved September 28, 2014, from http://greenfield.brynmawr.edu/items/show/1486

Thomas, M. C. (1901). Should the higher education of women differ from that of men. Educational Review, XXI, 1-20.

Young, C. (2014, January 10). This Is What I Mean When I Say "White Feminism" Retrieved September 28, 2014, from http://battymamzelle.blogspot.com/2014/01/This-Is-What-I-Mean-When-I-Say-White-Feminism.html#.VCjXUygfn5x

Comments

Reading your triptych

Submitted by Anne Dalke on October 4, 2014 - 16:49 Permalink

Hummingbird--

how had I missed, before, that piece you published about “understanding privilege” in the Teaching and Learning Together site? Taken together with this essay, and your more recent plea to our current group to grant one another more space, you’ve now put together a triptych. This centerpiece pairs the experiences of Thomas and Pratt, while the two outer “panels” look more explicitly and extensively @ your own: the first @ your coming to shocked awareness of the “knapsack of privilege” you bring with you into the classroom; the last @ our sometimes-unaware performance of passion, that silences (=dis-privileges) others who would speak. This is quite a line-up, and I thank you for seeing the need, and being willing to work and re-work this rich mine.

The core question you worry, in this paper, is your own presumption that progressive ideology in one sphere should? (must? why wouldn’t it? ) translate to progressive ideology in others. You take some time to demonstrate how M. Carey Thomas’s life exemplified precisely that “non-transferability.” I thought I knew Thomas’s story very well, but you’ve filled in a few details for me; I did not know of her shame when her mother opened their family home to “inferiors,” nor that her racist views were “increasingly calcified” by travel and exposure to Japanese culture.

You then do a very nice job of drawing on Minnie Bruce Pratt’s analysis of her own slow coming to awareness of intersectional oppression, in order to hypothesize about what might have been happening with Thomas—as well as in our current campus crisis. This section of the paper (that protecting her inheritance was possibly tied up with Thomas’s need to protect her sense of racial superiority) is of course speculative, but your hypothesis makes sense to me: that someone who is herself both giddy about and unsure of a newly solidified position (as a 19th c. woman with an education, as a 21st lesbian on the BMC campus) might well be unlikely to extend her privilege to others unlike herself, but move rather to protect her own vulnerability. There’s a psychologic logic to what you propose, and I find these very generous readings. I also think that they are acute and hopeful ones; they suggest that, with time, an awareness of oppression and vulnerability might well be transferable.

I hope that we’ll be able to apply these insights now to our own current class dynamics. In the earliest piece of your triptych, you describe your experience of recognizing that your class contributions were valued because you shared them “in the right way”: you came to college with “a knowledge and understanding of ‘socially acceptable’ or ‘socially encouraged’” forms of communication. I am wondering, as we talk on Tuesday about how we talk together, whether we will/can/should agree on a “right way,” whether the way you pose “passion” against “space,” “energy” against “openness,” “interruption” against “silence” are individually or culturally inflected pairings, which lay out not only competing desires to talk, but also different norms for respect and engagement. How much space can we, as a group, grant to such variability?

I’m very glad that you are keeping such questions on the table for us all.