September 28, 2014 - 22:50

Motivated by the recent events on campus regarding the confederate flag, and reflecting on my experiences in Africa, I was motivated to express my opinions about social change, both domestically and abroad in this piece titled, "Sustaining the Intersectional Perspective."

I have included some media that illustrate the concepts described within.

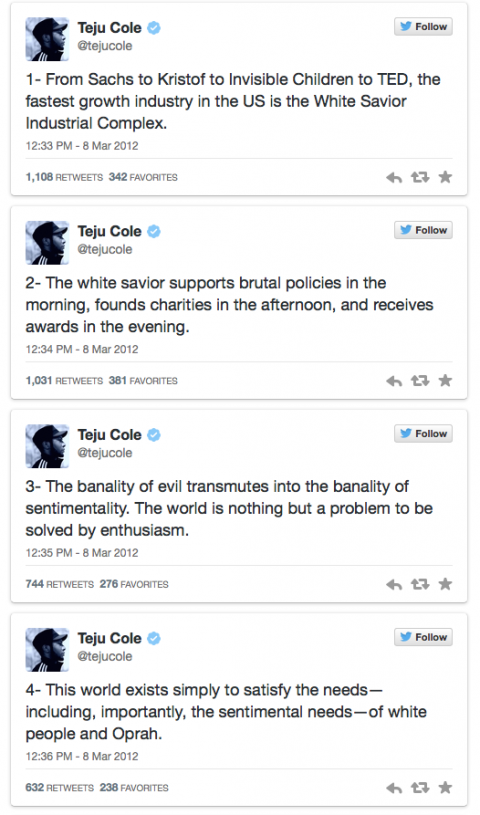

Teju Cole's "White-Savior Industrial Complex"

I took this photo at the end of the demonstration on September 19 at Bryn Mawr College. Over 550 students, faculty, and staff gathered in solidarity against opressive racial climates at Bryn Mawr and other elite colleges.

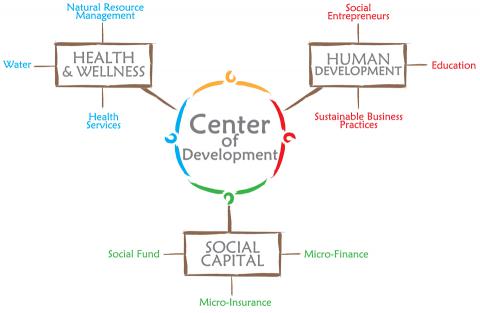

I am currently working for a nonprofit called Profugo through the Civic Engagement Office. This organization endeavors to enact sustainable development in India through implementing this model.

I could feel the current of strength and motivation at this demonstration, which I tried to capture in this photograph. Holding hands with my peers made me feel empowered, active, and aware.

Rebecca Cook

Sustaining the Intersectional Perspective

Intersectionality is contrary to the human experience of compartmentalization for understanding. These safe compartments contribute to a diffusion of responsibility in the world and reinforce the status quo. On one hand, when a white man travels to Africa for a service project, he can call himself a leader making a difference. That same white man can witness racist micro aggressions, uses of language, and thoughts that justify the marginalization of black people in America, but excuse himself as a participant and a reformer from that context because it’s not his problem. As a white person, he doesn’t need to have an opinion about how a black person is treated. As a person, his life is “morally neutral, normative, and average, and also ideal, so that when [he] works to benefit others, this is seen as work that will allow them to be more like us” (“White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack”). White people begin their lives with privileges they fail to notice others lack, and assume any contribution they themselves provide is accessible and productive. On the other hand, what is to stop a black man from continuing with his life instead of explaining to this white man how his actions affect others? Will this white man understand or even listen, based on his privilege? Also, why is it the black man’s responsibility to explain to the white man his own misdoings? While these divisive conflicts stand in the way of improvement, social justice actors can embody more personal and sustainable methods for change by recognizing instersectionality in domestic and international settings.

Peggy McIntosh offers one explanation for the passive attitudes that perpetuate this system:

Although systemic change takes many decades, there are pressing questions for me and, I imagine, for some [other white people] like me if we raise our daily consciousness on the prerequisites of being light-skinned. What will we do with such knowledge? As we know from watching men, it is an open question whether we will choose to use unearned advantage to weaken hidden system of advantage, and whether we will use any of our arbitrarily awarded power to try to reconstruct power systems on a broader base. (“White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack”)

From McIntosh’s perspective, it doesn’t just take an open-minded perspective to act upon injustices, but instead, change requires that one use one’s resources to fight oppression in every context. This motivation could manifest in correcting detrimental language that furthers the system of oppression, or making an effort to change some aspect of society that marginalizes others.

Mary Louise Pratt suggests a method -- based on critical conversation -- for recognizing discrimination and privilege in places called contact zones, which bring together people of different origins and different experiences to experiment, struggle, and approach working together in a way that challenges power in the status quo (34). These zones encourage the uninformed to see the intersectionality in each critical conversation, mainly the inclusion of all identities and the interpretation of a problem from multiple perspectives. Ideally, these critical conversations would take place in colleges or universities that encourage thoughtful discussion and boast diversity as one of their core values, but systemic prejudice prevents many with important opinions from gaining entry to these spaces. Alternately, those who can access these spaces might consider those spaces differently, maintaining the same inherently passive opinions as the black man and the white man mentioned before. Though students frequently read in class about oppression in the world and efforts to improve it, many maintain a different relationship to those opinions in the social context of the school. This status quo is also maintained by the bureaucratic nature of the college itself. In order to keep up an image of order and equality (in this business, the customer isn’t always right) the administration must act as one body that appreciates easily achieved suggestions for improvement but overall, supports the institution and all of its actions as a whole.

In order to encourage a renewed, more intersectional perspective, institutions may enable students to travel abroad in order to collect diverse opinions and improve the social environment of the school. These students might, through this experience, operate under the notion of the “White-Savior Industrial Complex,” a preoccupation articulated by Teju Cole. This identity arises from the guilt experiencing extreme poverty:

The White-Savior Industrial Complex is not about justice. It is about having a big emotional experience that validates privilege…There is much more to doing good work than ‘making a difference.’ There is the principle of first do no harm. There is the idea that those who are being helped ought to be consulted over the matters that concern them. (“The White-Savior Industrial Complex”)

I spent two months in northern Ghana the summer after my sophomore year, and one week in another region this past summer. As a white person with these experiences, I have solidified my opinions about racism abroad, and have gained new perspectives on racism within the United States. My first experience in Ghana had structural problems that rendered the program unsustainable. Further, this program intended to move towards a model of students developing their own projects before going abroad, assisted by their mentors. Given my experience, I would imagine students with privilege who might join the program would have difficulty in developing projects that are sustainable and address the needs of the community in which they will work. Without experiencing just how life works differently in the community -- in other words, experiencing that contact zone -- and without a way of collaborating on a personal basis with their mentors, students could easily slip into the mindset of the White-Savior Industrial Complex. Based on these experiences, I intend to approach any international work I do with the political science perspective of constructivism and the motivation to promote sustainability abroad, both of which utilize Teju Cole’s call to work for and with, not on behalf of, individuals abroad on projects that are of real concern to them.

The theory of Constructivism encourages actors to focus on the socially constructed nature of international relations. Mainly it recognizes that the Realist perspective (all nations only acting to maintain their own security and power) is a limited one that stifles critical conversations and action. Similarly, sustainable action considers every motivation in the context of what it will require to maintain a new system. Both of these perspectives encourage people abroad to have critical conversations about the on-the-ground needs of people in poverty about what needs must be met, and how they can be met in a way maintained by the people. From my experience I will remember most about Africa the conversations and contact zones I experienced with people I met there: Ibrahim’s description of his experiences in the corrupt school system, Sumaila’s frustration with his inability to go to college because he doesn’t have the financial resources or any political connections. I will also remember the serendipitous moments that showed me new ways of connecting with others: I once had a translated conversation with an old man at the bus stop who asked if I had lighter skin because “my people came first.” I was initially uncomfortable with the question, but then enjoyed explaining that actually, all humans came from Africa originally, and then moved to Europe and lost melanin in their skin through procreating in a different climate (a very simplistic explanation, I admit). At that same bus stop, I remember struggling to explain to a man that I couldn’t marry him because most people in America are monogamous, probably for financial and social reasons. Through these experiences and initially uncomfortable conversations, I feel empowered to use a more holistic perspective. I will consider the intersectionality of my identities and how they relate to the identities of the people I will collaborate with abroad. My experiences in contact zones will certainly inform how I use the money and skills I have been awarded through my privilege to try to better distribute privilege and means. Unfortunately, the White-Savior Industrial Complex kept many aspects of my international experience afloat, rendering it unsustainable and harmful to the community, and that makes me angry: angry to ask critical questions, to challenge unsustainable actions, and to contribute positively to a world with so much destructive, offensive international action.

Considering the globe abstractly, one might find it easy to characterize problems abroad, including poverty, infrastructure, racism, and corrupt governments. Honing in on a domestic level, America could never be conceived as having these same problems because so many white people live under the guise that they are comfortable, so everyone must be. The current state of American social affairs with regard to marginalization mimics Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.’s short story, “Harrison Bergeron.” This piece recounts a society in which people are forced to take on physical disabilities, including jarring sounds being played in their ears when they try to think, in order to ensure that everyone is equal. In the context of America, our privilege is our disability; we fail to see the problematic systems that don’t directly affect us, and the status quo proceeds, untouched, with the same marginalization. We get caught up in the current moment of receiving the most likes or keeping our email inboxes clean with no regard to our past, trajectory, or actions wielded with privilege.

In tandem with efforts abroad, domestic social change actors must recognize their privilege. They must speak out when they witness discrimination, and not be afraid to be criticized for things they do that might hurt others. They must consider both the trajectories and pasts of marginalized populations, not in a way that holds grudges, but with the motivation for changing what factors marginalized people yesterday. Further, they must track improvement for the sake of sustainability. These actions call for personal conversations, discomfort, and a kind of loudness that will agitate the status quo in a way that makes necessary improvements. As a sociologist, I am inspired by the notion of collective consciousness, a term Emile Durkheim coined, describing shared beliefs and the power that comes from a group united in beliefs. I’ve seen this feeling manifest in situations of intersectionality: two people connecting in the shared experience of losing a parent, or gathering at a march for breast cancer awareness, motivated by witnessing someone crumble at the hands of the disease. These experiences transcend differences of race and class and motivate people to enact change that lasts and is meaningful. The demonstration on September 19 allowed students, faculty, and staff to show solidarity in changing the on-campus racial climate that allowed a confederate flag to be displayed on campus as a symbol of pride. The demonstration showed me a collective consciousness I have never felt before, full of support and solidarity. I felt present in a way that opened my eyes to the power of the people around me and the future we hope to achieve and sustain, both at Bryn Mawr and at other elite colleges. This experience empowered me to feel that I am here, I am current, I am intersectional, and I am angry.

Bibliography

Cole, Teju. “The White-Savior Industrial Complex.” The Atlantic online. March 21, 2012. <http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/03/the-white-savior-industrial-complex/254843/> Accessed 9/28/14.

McIntosh, Peggy. “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” Independent School, Winter 1990. <http://ted.coe.wayne.edu/ele3600/mcintosh.html> Accessed 9/28/14.

Pratt, Mary Louise. "Arts of the Contact Zone." Profession (1991): 33-40. PDF.

Comments

constructivism

Submitted by Anne Dalke on October 4, 2014 - 16:52 Permalink

rebeccamec--

I’ll start with my curiosity about a couple of “displacements” here: why you posted your paper as an attached document, rather than as a web event (I’d prefer the latter, as more accessible), and why you delay talking about your own experience until almost p. 4, discussing instead the (fictional? imagined? generalized?) experiences of “a white man traveling to Africa for a service project,” rather that what you yourself know experientially…

Your project is an ambitious one, wide-ranging from white privilege in this country (including the current controversy on campus), to service projects abroad; you gesture in so many different directions that there’s much more I want to know-and-discuss. You begin by juxtaposing intersectionality with compartmentalization—and describe the latter as a state of “diffused responsibility.” So, for starters, I want to understand that claim better: how “diffuse,” if “compartmentalized”? McIntosh’s classic essay is very useful to you here, but I’m puzzled about how you are using Pratt. You place intersectionality in the contact zone, but I think (did we talk about this in class?) that one of the problems with her piece is that it really doesn’t acknowledge intersectionality, but rather advocates the possibility of critical conversation among self-identical, coherent actors, assumed representatives of their cultures, rather than among people who are themselves ‘contact zones’ within, whose identities are intersectional, who are uneasy, unsure, not fully self-knowing (I think here of Minnie Bruce Pratt’s complexly and long-unfolding story of privilege that was disability, and only very slowly uncovered…)

Another term new-to-this-conversation is “sustainability,” which I know from my work in environmental studies, and which is also a complicated one for me--and I think could prove quite a complicating factor in our analysis of both identity matters and community making. I myself haven’t yet figured out the relationship between accountability and sustainability. If we want our relationships not to be scripted (not, as Eli Clare says, “transactions designed to set us against each other”), but rather open to serendipity and surprising engagement (like those several you describe @ the bus stop in Ghana), then how to make sustainable that which is not repeatable? How make sustainable the unique and unrepeatable acts of true teaching and learning? How to acknowledge what we don't/can't know, the unpredictability and surprise of our educating ourselves and others?

These questions are directly related to another of your (sub) topics, how “the bureaucratic nature of the college” maintains the status quo, and also to your pursuit of the theory of “constructivism,” a focus on the socially constructed nature of international relations”—as well as those @ home. So, if we refuse the “realist” presumptions that each-and-all act only to “maintain their own security and power,” with what presumptions do we replace them? What are agents (individual, collegial, national) working to “maintain,” to “sustain”? How to do—and how to critique-- that sustaining work? And how to keep that labor both subtle and differentiated, especially if you are committed to the emergence of a “collective consciousness,” to forming “a group united in beliefs”? What happens, in such solidarity and transcendence, to the differences that a theory of intersectionality keeps alive?