September 30, 2014 - 20:51

World War I was one of the most horrifying wars the world has ever seen--trench warfare has been described as hellish muck, among other things. Unfortunately, one of the surprisingly common outcomes of trench warfare was injury to the face. A soldier would stick their head out of the trench, and lo--a shell explodes, and your face is gone, if you're lucky enough to survive. Those men that did survive were horribly disfigured. To help the healing process, many armies sponsored artists to create "portrait masks" for the afflicted veterans, a form of facial prosthetic, so they could regain some sense of a normal life.

The work of Anna Coleman Ladd, as profiled by NPR in this recent story, is one of the most remarkable examples of portrait masks. She had an incredibly detailed process to creating these masks in her studio, much like the process Riva Lehrer discussed in painting a portrait. She wouldn't just seek to create a "normal" face for the veterans, but instead seek to get to know them, their families, their personal preferences, and not just use photos of how they looked before the war. These masks of copper, plaster, and paint, fitted custom to each person's face, were truly wearable portraits, at the same time they were prosthetic devices.

However, these masks were not "functional" prosthetics--they couldn't move or be used to eat, for instance. They would always be set in one expression, one skin tone, and could not move. When we think of a prosthetic, we usually think of something functional, something moveable. We think of hands, of legs, of even implanted eyes. Faces, though, are not moveable appendages like limbs. Faces are the sensory and intake centers of the body, but more than that, they are highly evolved methods of social communications. Thus, these masks are not so much "functional" prosthetics as social prosthetics.

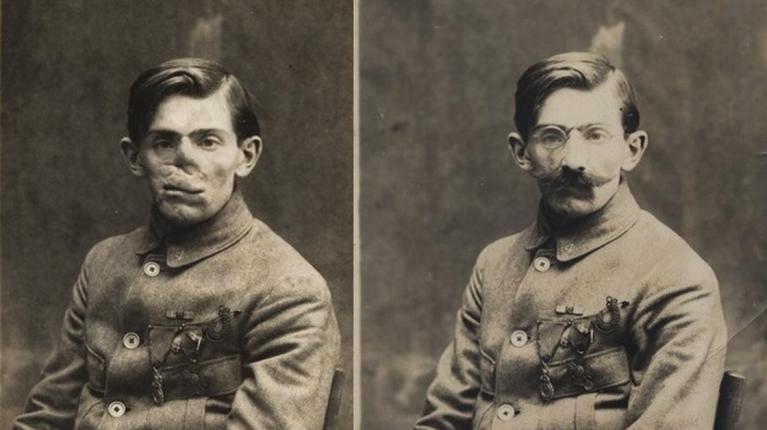

Though they might be tricks of the light, and appear very similar at first glance, these two portraits of a patient of Ladd's actually have remarkable differences other than the obvious (that is, the mask). Common to both portraits is the haircut, the major positioning of the body, and the outfit. Even the background and the chair are the same. The haircut is a typical style of the time-period, waxed into place with hair cream, a standard man’s haircut. The subject wears his uniform, though I’m not sure whether it’s his duty or his dress uniform (likely dress), with all of his medals pinned in full view, front and centered. The general pose is a typical portrait bust pose, meant to show off and accentuate the natural shape of the shoulders. It was also typical, as in many portraits today, for the subject to be looking straight at the viewer. His gaze is strong and steady, almost confrontational in its directness, as if he were trying to look through the picture and into your eyes (or, in the case of the photographer, through the lens and to the cameraman’s eyes). Clearly, these two portraits must have been taken minutes apart—virtually every hair is in the same place.

Other than the obvious change of no mask to mask on, the fine details are where you can find many social cues. In the left-hand portrait, the man is slightly slouched, showing how conscious he is of the deformity of his face. Even though he looks straight at the viewer, his chin is slightly turned away off the typical 45 degree angle of this portrait pose. The little area of his face that he is able to show expression in, his eyes, are steady and almost challenging, even as they have a concealed mournfulness to them. He is proud of his service and sacrifice at the same time he knows the effect on others of his tragic deformity. By contrast, in the right-hand picture, the man sits straighter up, shoulders squared in pride, the entire picture brighter in tone. He stares at you much straighter-on—the semblance of normalcy, of not being so starkly ugly, has given him back enough confidence to take more pride in the medals on his chest.

His unmasked face is what society even now considers the stuff of horrors. He lacks much of his nose, his mouth has been misshapen, and he likely lacks much of the zygomatic (cheek) bone on the right side of his face—flesh is missing all around it. And this is after reconstructive surgery! Misshaping and deforming of this type will often bring to mind visions of mortality for the viewer, as well as a sheerly visceral sense of horror at something so uncanny. These such injuries bring remiscences of the horrors of war, a reminder for both the person, daily, of the horrors they suffered in the trenches, and for their loved ones. Even for people on the street, when they did indeed venture out, were a sight of horror. These masks, made as portraits of who the wearer wanted to be seen as, as best as was able with the technology of the World War I era, were prosthetics which allowed men to lead more normalized lives, to be seen as something more than their wartime injuries.

(This video also sums up the process of mask creation quite nicely)