December 19, 2014 - 11:14

Katie Hinchey

Identity Matters 360

Dalke, Lindgren, and Nath

December 19th 2014

#AllBlackLivesMatter: The Creation of an Intersectional Movement

Introduction

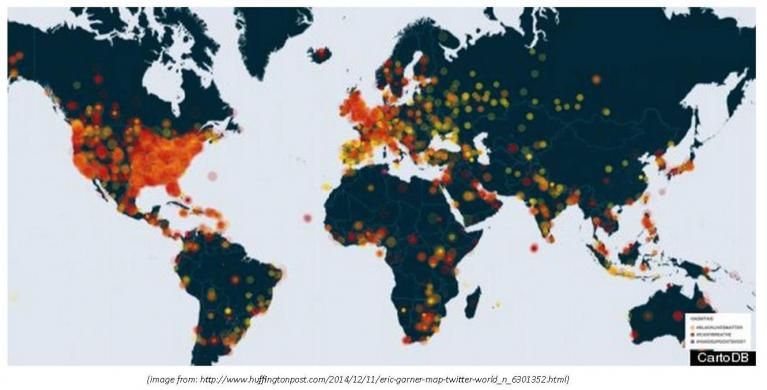

Racism continues to permeate American society, most recently police brutality and specifically the high rate of police murders of Black men is at the center of public debate. “Every 28 Hours”, a chant referencing the harrowing statistic that every 28 hours a black man is murdered by the police or a vigilante is being heard in marches in hundred of American cities. Though a black man is killed by the police almost everyday, the murders of Mike Brown, Eric Garner, and the failure of their respective Grand Jury’s to indict the officers catapulted this long standing systemic issue to international public discourse. The map below is a visual representation of the rapid spread on Twitter of the hashtags #ICantBreathe (yellow) and #ICantBreathe (red) on December 3rd and 4th-the days following the announcement of Garner’s murderer walking free.

In this paper I intend to explore the strengths and weaknesses of the emerging, newly invigorated movement towards racial equality. Through a analysis of emerging Black female leaders all across the country I will argue that the other leaders of the movement could benefit greatly from a more complex lens through which to view interactions within these new movements.

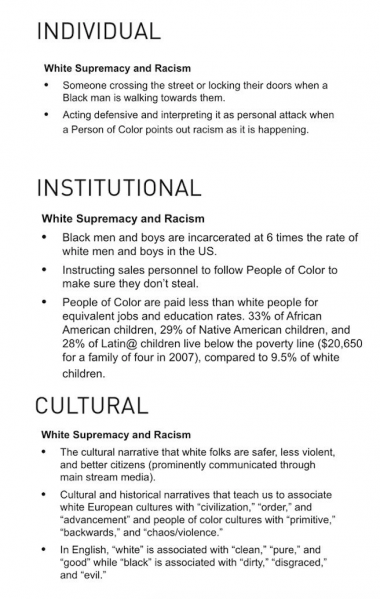

The issues affecting Black Americans certainly do not begin or end at police brutality. The legal system is built to be stacked against people of color. There are currently more incarcerated Black Americans than there were enslaved Black Americans in 1850. (Muhammad) Black Women are also the highest growing prison population. Disparities in the amount of arrests, prosecutions, and sentencings effect every Black American who comes into contact with the legal system. It should go without saying the racism does not only effect the justice system. The Anti-Oppression Training and Resources Alliance (AORTA) publishes quarterly anti-oppression resources that provides clear, accessible imagery of how different oppressions like racism are experienced in different levels. I have created the visual below to give a small example of the resources they have gathered:

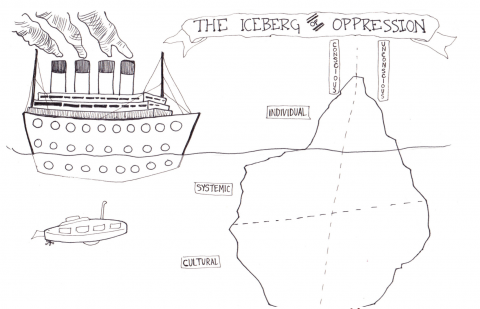

Another problem is the narrative that oppression only happens through the individual level. Many American’s have subscribed to this false notion. This erases the larger systemic problems in the justice system. AORTA uses the metaphor of an “Iceberg of Oppression” to explain how the pieces comprising these systems of oppression are much deeper than individual actions. In the figure above, the peak of the exposed iceberg represents the individual actions and experiences of everyday racism. Underneath sea-level the iceberg is much larger representing the institutional and cultural reinforcements of racism. The approaching boat can be a metaphor for groups coming into contact with oppression. Those at the top of the boat really struggle to see the much larger systems hidden under the waterline.

AORTA’s close reading of the experience of those who are trapped in the hull and why we must trust in their lived experiences how drowning underwater affects them connects with the experience of Black Americans. This narrative argues that if those with the privilege (seated above the water) ignore the knowledge of those trapped below, the entire ship will come crashing down.

Intersectionality and Coalition Building

When Kimberle Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” in 1989 she changed the discipline of women’s studies forever. Crenshaw, in a 2004 interview with Perspectives magazine summed up the creation of this theory:

“It grew out of trying to conceptualize the way the law responded to issues where both race and gender discrimination were involved. What happened was like an accident, a collision. Intersectionality simply came from the idea that if you’re standing in the path of multiple forms of exclusion, you are likely to get hit by both. These women are injured, but when the race ambulance and the gender ambulance arrive at the scene, they see these women of color lying in the intersection and they say, “Well, we can’t figure out if this was just race or just sex discrimination. And unless they can show us which one it was, we can’t help them” (Thomas 2).

This analysis is particularly applicable to the #BlackLivesMatter movement. Applying intersectionality to the work to eradicate these issues more comprehensively captures the complex nature of the human experience. Intersectionality brings the perspectives of previously ignored subordinated identities into larger awareness by highlighting the how the system is cracked in almost endless and interwoven ways. Crenshaw argues, “Recognizing the ways in which the intersectional experiences of women of color are marginalized in prevailing conceptions of identity politics does not require that we give up attempts to organize as communities of color. Rather, intersectionality provides a basis for reconceptualizing race as a coalition between men and women of color” (Crenshaw).

As the grassroots movement towards racial equality expands at a rapid pace we can apply both intersectionality and the iceberg to coalition building. Intersectionality is not only an important personal lens to bring into activist movements but the coalitions we are building must take on this identity. If we argue that we bring our intersecting identities to movements we are involved in should they not be read as intersectional as well? Why do we focus so intensely on the importance intersectionality plays out in our own lives and not how the groups we find ourselves in identifying with do not always apply intersectionality to building coalition? In order to build successful social justice movements, I argue that we must eradicated the homogeny of these groups and encourage reciprocal support.

So often we spend our time building coalitions that focus on the celebration of the realization of our intersectional identities instead of using our new found understanding to move forward together in a group that both constructively critiques and celebrates how our differences affect our group dynamics and how to move forward. This stunted application of intersectionality is causing pain and suffering for those who are being left out of advocacy work or silenced when they finally receive their seats at the table.

Who’s Lives Matter?

This problem is happening both inside and outside communities of color. Stories of the many different types of people facing discrimination are not being picked up in larger Post-Ferguson discourse. Most of the media coverage and public debate has focused on the violence against Black cismen. Black men are not the only ones in danger. The rates of police violence against black ciswomen and black Trans*women are staggeringly high. What is causing this erasure of experience in a movement that claims to rally itself around the mantra #BlackLivesMatter?

One argument put forward to explain the invisibility of violence against women is that it is based in the larger patriarchal narrative. Kristin West Savali claims,

“Without qualification or deflection, we must address the very real fact that perpetuation of White supremacist capitalist patriarchy depends on the state-sanctioned murder, mass incarceration, and vilification of Black men. Power and dominance is typically contextualized within the construct of cisgender masculinity, leaving the brutalization of Black women, even when it mirrors that of Black men, as an afterthought… Very seldom is the violence inflicted upon Black, female bodies by law enforcement positioned as pivotal to justice movements; rather our lived experiences as victims of the state tend to be peripheral and anecdotal” (Savali).

Groups working towards racial equality and resistance to violence often presume that the victim is a black male. This makes violence against women the exception to the rule instead of addressing the cases of violence as symptoms of a continuous problem. (Savali) If groups continuing working towards racial equality operate under the assumption that all who face discrimination for one part of their identity will experience it the same way. This would mean that new coalitions like #BlackLivesMatter and #ICantBreathe would not have survived. Thank god for the Black women who have been fighting endlessly for their seat at the table.

Trans*women of color are not new to fending for themselves against violence and discrimination-often within communities with other people of color. Their experience with law enforcement officers are more often negative than not and include discriminatory and traumatic procedures. Stories of police brutality against transfolks can be found here and here. #BlackLivesMatter co-founder Patrisse Cullors theorizes that,

“transphobic acts of violence are often rooted in maintaining a hetero-normative and binary notions of gender. These same notions of gender describe Black men as criminal, aggressive and deserving of excessive force. Therefore it is not possible to challenge one without taking on the other and it is time for cisgender Black people to be proactive about defending the rights of Black transgender women as an investment in all Black Lives. It is time that we have courageous conversations in our communities that acknowledges the complicity and lack of action and response for Black trans lives," says Hunter. "This year, 12 trans women of color were brutally murdered in a 6 month span in this country with no national outrage. For our collective liberation, it is imperative that we acknowledge how structural violence manifests in all our lives” (Cullors).

Fortunately activists like Cullors are part of a growing number of intersectionality focused leaders. In the next section I will do a close reading of intersectionality’s influence on the Post-Ferguson movement through the leadership of black women. These narratives of activism by women of color are influenced by their own lived experiences as people who are “multiburdened”. These Black female activist's experiences cannot adequately be represented by just one or two of their identities and who therefore have chosen to do their work through the lens of intersectionality.

Intersectional Leaders

In the first few days after Mike Brown’s murder the people of Ferguson began to organize and protest in the streets. One of the grassroots organizations that has catapulted to the forefront of the movement, Millenial Activists United is run primarily by women. These women came together to provide food, emergency medical aid, and to lead the rallying cry for justice. In an October interview with TheFeministWire the leaders of the group spoke out about the police violence against protestors, sexism within the movement, and their fight for a larger platform with which to tell their stories and move towards social justice for all. In this interview, the MAU founders are direct about their intention to keep the movement moving towards complete intersectionality.

The women of MAU are in very good company. The organization #BlackLivesMatter was also founded by three women; women who on their first project worked with two queer black leaders to organize a nationwide influx of community leaders to Ferguson (Giorgis). Despite the void of mainstream attention being paid to violence against black cisgendered women, black trans women, black gender-non conforming and black these activists are not deterred from speaking out and pushing to make spaces. Just this week, one of the founders of #BlackLivesMatter published an op-ed on Ebony calling for the decentralization of the violence against cis- men and women. In the article “From Ferguson to New York, women are leading protests because all #BlackLivesMatter” Hannah Giorgis writes,

“The most recent dynamic leadership of black women on the front lines in Ferguson and cities across the US reflects what black women understand intuitively by virtue of our own experiences: the radical power of black women-led activism lies not in token representation for the sake of optics, but in deep, meaningful attention to intersecting oppressions and the solutions that emerge from understanding them. It maintains that we are all affected differently by injustice and must address its multiple iterations simultaneously– that “nobody’s free until everybody’s free."

Though the pressure and discouragement Black women encounter adding their intersectional voices to the debate can be a rewarding experience. Synead Nichols came home from protesting the evening Darren Willson was not indicted fired up and wanting to make change. “So I decided to make the Facebook event in the hope that a few people would come together in solidarity. Then I reached out to Umaara, and before she even agreed to hop on board I made her a host of the event page. And we just kind of took it over from there.” (Fleming) The facebook event took off and over 500,000 people were invited to the march. 50,000 of those people showed up on the afternoon of December 13th to show their support and process police brutality together. This march, while one of many in the past 14 weeks was certainly one of the largest.

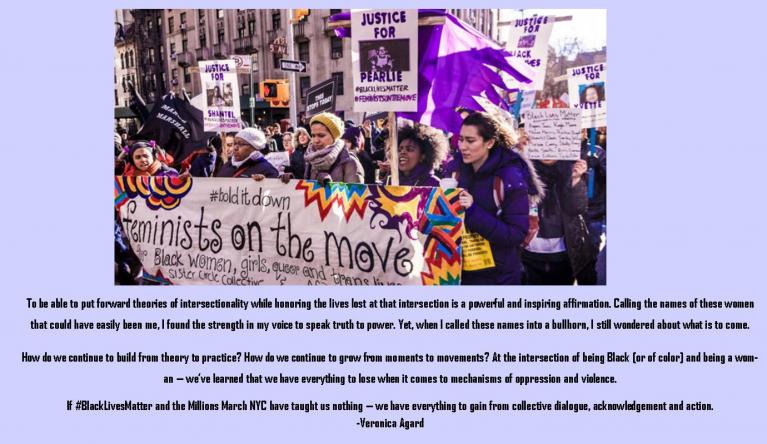

The model of intersectional justice also permeated the march itself. Two feminist groups the Sister Circle Collective and AF3IRM NYC combined to work on raising awareness of violence against black cis- and trans- women under the name ‘Feminists On The Move’. Although the group had anxiety about how they would be received they were “met with an overwhelming amount of support-including that of the creator of the term intersectionality itself, Professor Kimberle Williams Crenshaw.” (Agard)

Crenshaw’s theory of intersectionality benefits those doing this work immeasurably. If more activists follow the lead of #BlackLivesMatter and #ICantBreathe by moving towards the complex lense of intersectionality we will start to see movements steer away from icebergs of oppression. More activists leaders must take a minute to look underwater at the larger oppression Black women are facing while they put their lives on the line to do this work. By validating the experience of and learning from the black women who are doing this amazing work, activists fighting against oppression for their subordinated identities can also make important changes and truly create the safe spaces that they are so often fighting for themselves.

Works Cited

Agard, Veronica. "Black Women's Lives Matter Too: The Forgotten Victims of Police Killings." TheGrio. N.p., 14 Dec. 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. <http://thegrio.com/2014/12/14/black-women-lives-matter/>.

Anti-Oppression Training and Resources Alliance (AORTA). “The Iceberg.” Resource Zine (Spring 2014). <http://aortacollective.org/sites/default/files/2014_resource-zine_final.pdf/>

Braswell, Kristin. "#FergusonFridays: Not All of the Black Freedom Fighters Are Men: An Interview with Black Women on the Front Line in Ferguson - The Feminist Wire." The Feminist Wire. N.p., 03 Oct. 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. <http://thefeministwire.com/2014/10/fergusonfridays-black-freedom-fighters-men-interview-black-women-front-line-ferguson/>.

Cullors, Patrisse. "ALL Black Lives Matter." EBONY. N.p., 18 Dec. 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. <http://www.ebony.com/news-views/all-black-lives-matter-504#axzz3MLfdA4gp>.

Fleming, Olivia. "#BlackLivesMatter: These Two Young Women Rallied 50,000 to Protest Police Brutality in NYC." Elle. Elle Magazine, 18 Dec. 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. <http://www.elle.com/news/culture/unmaara-elliot-synead-nichols-millions-march-interview>.

Giorgis, Hannah. "From Ferguson to New York, Women Are Leading Protests Because All #BlackLivesMatter." Comment Is Free. The Guardian, 15 Dec. 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. <http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/dec/15/ferguson-new-york-women-protests-all-black-lives-matter>.

Korn, Gabrielle. "This Is What It's like to Be a Youth Activist in Ferguson." NYLON. N.p., 2 Dec. 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. <http://www.nylon.com/articles/brittany-ferrell-interview>.

Muhammad, David. "Black Lives Matter: It’s More than Police Killings." New American Media. N.p., 15 Dec. 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. <http://newamericamedia.org/2014/12/black-lives-matter---its-more-than-police-killings.php>.

Rodriguez, Princess Harmony. "Whose Lives Matter?: Trans Women of Color and Police Violence -." Black Girl Dangerous. N.p., 09 Dec. 2014. Web. 15 Dec. 2014. <http://www.blackgirldangerous.org/2014/12/whose-lives-matter-trans-women-color-police-violence/>.

Savali, Kirsten W. "Black Women Are Killed by Police, Too." DAME. Salon, 8 Aug. 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. <http://www.salon.com/2014/08/24/black_women_are_killed_by_police_too_partner/>.

Thomas, Shelia. "Intersectionality: The Double Bind of Race and Gender." Perspectives Magazine (2004): n. pag. American Bar Association, Spring 2004. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. <http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publishing/perspectives_magazine/women_perspectives_Spring2004CrenshawPSP.authcheckdam.pdf>.