November 25, 2015 - 22:41

I saw this image on twitter and it stuck with me.

In The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander discusses the most recent iteration of the fundamentally racist system that exists in the United States: mass incarceration. Just like their ancestors, many black Americans cannot vote and are denied rights, only this time it is justified by their criminality. Their fathers were kept under control through fear and the guise of state’s rights. Their father’s fathers were controlled and dehumanized by slavery.

Today, someone can lose their job for saying something explicitly racist. A white girl and a black boy can kiss each other in the hallway of my high school and no one bats an eye. Public water fountains no longer say “white" or "black only." But racism today is still alive and well. It just goes by other names. Black people are disproportionately represented in prisons and underrepresented in higher education and government: they make up 13.2% of the general population ("USA QuickFacts") and close to 50% of the U.S. prison population, incarcerated at nearly six times the rate of white people ("Criminal Justice Fact Sheet."). The 113th U.S. congress contains 43 African American Representatives and one African American senator, in total 8.2% of congress (but only 1% of the U.S. Senate). Of the many faculty at Bryn Mawr College, only five are black.

And yet, racism is often understood as isolated events perpetrated by extremists. But the truth is racism is embedded in the systems in which we exist and in our understanding of the world. Racism is imbedded in our institutions and in microagressions and prejudices that we may not even be aware of. One white student describes her racist reactions when riding the subway:

"that gut sinking felt

when a tall black He

grabs the pole next to you on the

subway

late at night, going home

…

And you smile at him

All the while certain that

He knows

That he saw through that crinkled white wrapper

with the charcoal-smudged smile

and the eyes

that for some reason or another

can’t quite meet anyone else’s” (Butterfly Wings).

Her fear, however slight, was based on a racist implicit bias. As she writes on, her thoughts explode, she is sorry: ‘"IT’S NOT YOUR FAULT,”’ she shouts in her mind. Is it her fault, either? This racist beast envelopes us all. We may not all be guilty, but we are all responsible (Abraham Joshua Heschel). Rather than pretend we are immune from racism, we must confront it, we must change the system.

So now what? How do we move forward? It will be hard to change people’s minds, but maybe if we start with the structures, the institutions that perpetuate these injustices, we can create a better future. We must simultaneously address the symptoms and attack the disease. I wonder what we can learn from education in prison in understanding these issues of racism and mass incarceration. How can we both work with incarcerated individuals to somehow address the effects of these oppressive structures and at the same time seek to prevent incarceration and dismantle oppression? My thoughts turn to primary education, to the “school-to-prison pipeline.” Perhaps some reflections on education in prison can shed some light on education before prison.

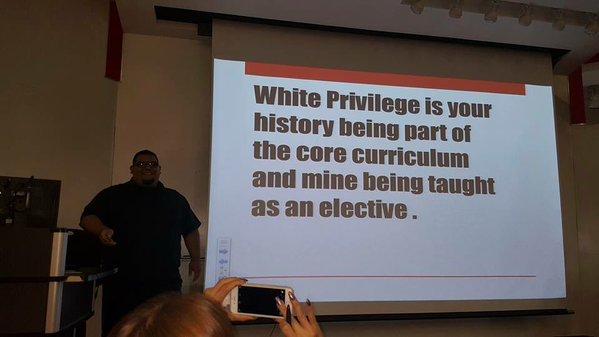

White Privilege is your history being part of the core curriculum and mine being taught as an elective.

Knowledge is power, yes, and knowledge of one’s self and one’s past is especially empowering. Nathaniel Moore seeks to empower black men by teaching African history in San Quentin State Prison. Moore’s course selection is inspired by the African principle of Sankofa: "Translated from Twi, it literally means 'go back and get it,' or 'return and get it.' Figuratively, it symbolizes the importance of knowing one’s past to build a successful future” (Moore 57). By studying African history, those incarcerated individuals with African descent (a large percentage) are able to better know themselves and their past, making them more confident. One student reflects on the course: "The understanding I received of myself and the self-worth, of knowing that I came from a rich tradition gave me a lot of self-worth and pride” (Moore 57). As the students began to understand and value their past more—and non-black students also learned to appreciate African history—they became more empowered “to develop their own identities and communities” (Moore 65).

I took African Religion at Haverford last semester and experienced a huge turn-around in my understanding of traditional African religions. On one of our first days of class, we did a word association activity with “African Religion,” “black magic,” and “Voo Doo.” I didn’t know much about the first two, but came up with many pop-culture references to Voo Doo involving creepy controlling dolls (the TV show Parks and Recreation and the movie Meangirls, are just two examples). Throughout the course, I often reacted with skepticism to ideas such as manifestation, herbal rituals, and animal sacrifices, dismissing them as crazy and superstitious. The more I learned, though, and the more I tried to reject my prejudices (and remind myself of the weird things we do in my religion), the more I appreciated the spirit and beauty of these religions. I still hold a lot of these biases, but many fewer than before I took the course. But why did it take until college for me to even know that these African religions exist? In the brief unit we did in 7th grade world history on religions of the world, we did not learn about any African Religions. Even in the discipline of Religion, there often are not seats at the table for scholars of African Religion. It is not seen as legitimate: this is another way to be racist without calling it racism. There were only four students in the course. I don’t think taking this class put much of a dent in today’s system of racism.

Moore warns that teaching African history in prison is not the answer or the solution to mass incarceration, which has done “incredible damage to Black, Brown, and poor communities across the United States” (64).

To take Moore’s insights to the next level, to a possible solution, I suggest we incorporate the idea of Sankofa into primary education. I believe the same histories that empower incarcerated people can empower young people and help to cut off the school-to-prison pipeline.

White Privilege is your history being part of the core curriculum and mine being taught as an elective.

Last Thanksgiving, my sister, who was in kindergarten at the time, wore a costume she made at school: an “Indian” headdress and vest. When I was her age, I lived in Massachusetts where I was taught the proud history of the Mayflower and the joy of Thanksgiving. We celebrated Christopher Columbus Day with skits about the Nina the Pinta and the Santa Maria and other activities. I don’t remember how old I was when I learned about the destruction of Native peoples. When did I start to resent Christopher Columbus Day as a day of colonialism, oppression, destruction and loss? Maybe seventh grade? Not early enough. History should not be about pride; it should be about truth. I told my mom I disapproved of my sister’s costume.

It is imperative that we study and value those cultures that are marginalized in the world. Our education has political implications. The personal is political; the educational is political.

And we need to bring ourselves into our spaces of learning. We need to know where we are coming from to be able to move forward (Moore 57). We need to weave together the personal and the academic. And yet, there are limitations and challenges in actualizing this ideal. Asking students to bring their personal experiences into the space can put enormous pressure on oppressed people to break powerful silences. Before we can bring ourselves into the space, we must create safe spaces. We should work together and lift ourselves up together. Education should be collective, not competitive. It is in the interest of us all to learn, to grow, to inherit the world as it is and transform it into the world we wish for it to be (Alinsky 3).

Works Cited

Comments

"bringing ourselves into spaces of learning" - which selves?

Submitted by jccohen on December 5, 2015 - 10:55 Permalink

Shirah,

Your cataloguing of contemporary racism early in this essay is effective, as you move back and forth across time and space, landing close to us with the words of Butterfly about race and fear.

Then you take us to the notion of education as a possible space to intervene in these deeply embedded ways of being and behaving that are themselves etched into structures… And it seems to me that here you would do very well to actually look at schools, and particularly at Irizarry and Raible’s analysis of “epidermalization” as a way to ground your examination of Moore’s course based on the concept of Sankofa. Great idea about incorporating Sankofa into early education.

Here’s a conceptual question that I think your essay implicitly raises and could really delve into: Moore and also Gaskew argue for education in prison that is specifically tailored to the population of students; that is, the call is for “marginalized groups” to learn their own history. Your own experience taking the African religion course at Haverford is in some sense more like the article we read earlier in the semester about learning about the Holocaust; the focus here is on learning about the history of “marginalized” others. How should we think these about the value and perhaps the relationship between these different approaches to the issues you raise here re: education as a way to address profound power inequities?

re: which selves?

Submitted by Shirah Kraus on December 6, 2015 - 09:42 Permalink

Thank you for your comments. I think there was this part of me that was avoiding my own experiences learning about my own culture and history (Judaism). When it comes to the articles we read, Sankofa and African history was learning about the self and the Holocaust was learning about the "other." For me, it is the opposite. I didn't have the best experience at my Jewish day school, but I wonder how learning about my Jewish past and self has shaped and motivated me--and how does this connect to and illuminate the theoretical texts.