The Message of a Museum: Continuing to Silence Stories of Violence in the Colonial Past

When was the last time you visited a natural history museum? Can you recall what you learned about culture, other people, and maybe yourself? In our presentation, we ask you to question the ways you read a museum exhibit with a view to the ways “cultures meet and clash, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical power relations, such as colonialism or its aftermath” and your knowledge of the contact zone (Pratt). We will ask you to be conscious of the many ways that the museum experience is tailored to the viewer and inherently neglectful of full human experiences. I, Creighton, and my partner Maryam have found that museums have used-and continue to use-silence as a tool to distance the viewer from the contexts of artifacts that should be included in order to acknowledge the injustices suffered in the colonial tradition of exploitation.

The museum is a way for the public to encounter cultures and hear stories they wouldn’t be able to on their own. They have succeeded in centralizing and distributing knowledge in a way that is accessible and comprehensible, but museums have also failed to attribute credit where credit is due, among other things. Natural history museums in particular, or museums that contain records of living organisms, have struggled in the past to create exhibits that engage the cultures from which artifacts are extracted from, obtain them in an ethical way, and present them in a way that does not perpetuate colonial ideas. In short, they have had to navigate “putting [culture] on display without the input of people involved”.

To understand the always problematic and sometimes disastrous effects that museum exhibits can have, think about a few examples we came across in our research:

“The Smithsonian had a display up until the ‘80s of human racial ‘types.’ They had a man there who was a eugenicist, and those old racial types on display” (Scott).

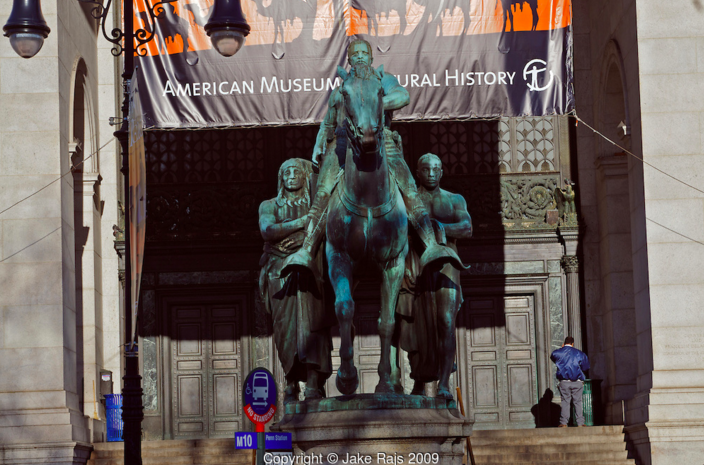

At the American Museum of Natural History, a “statue of Teddy Roosevelt on horseback was flanked by a Native American and African American.” It has been protested in the form of “graffiti on the side of the statue” for its racist undertones (Scott).

Bryn Mawr’s African Art Collection, consisting of some objects that do not attribute credit to the original artists.

In our interview, we learned that natural history museums have a troubled past of appropriation and erasure. Originally, museums were intended to “civilize” the general public by putting other cultures on display. The etymology of the word “curio,” (cabinets housing curios were precursors to the museum) reveals that it initially referred to a “piece of bric-a-brac from the Far East” (Etymology Online). The word points towards a precedent of collecting non-Western objects for display, which is a practice that has worked to misrepresent, exoticize, and colonize societies since its inception.

The museum exhibit is a highly manipulable medium of discovery, a pre-prepared way of learning that is influenced first by curators and later by viewers. Within it, history is never unedited and always abridged. In our six-week project, we combed through blog posts and articles about controversies in museums related to the presentation of non-Western cultures. The main problem we encountered in museums is the tradition of silencing other cultures.

I (Creighton) was inspired to research this topic because of a previous exhibit on display at Bryn Mawr College, called Backtalk: Exposures, Erasures, and Elisions of the Bryn Mawr College African Art Collection. We were lead to a blog post written as a reaction to this exhibit by Grace Pusey (who is also helped create the Black at Bryn Mawr tour). Her post summarized many of the uncomfortable practices that are normal in museums, particularly the erasure of the original artists, writing that “most of the items in the Collection do not have an artist’s name listed and are instead credited to Neufeld and Plass, their collectors, or to the country or ethnic group from whence the object originated. (For example, multiple items have “Uganda” listed as both ‘artist’ and ‘place of origin.’) It seems unlikely that Neufeld and Plass did not have access to artists’ names; rather, both collectors deemed such information unimportant” (Engaging “Backtalk”: Decolonizing Bryn Mawr’s African Art Collection).

We discussed the long, complicated past of the natural history museum, in America and elsewhere in an interview with the Director of Museum Studies at Bryn Mawr College, who had done work on natural history museums in Africa as well as England. We were interested in the way that African natural history museums displayed their own cultures, especially in an institution whose history is tied to colonialism and appropriation. The interviewee told us that they “found that Africans were not presenting African culture. [They] found that the black Kenyan visitor-the visitors of African descent- saw the museum as something not created for them. There was a very palpable sense there of exclusion”. This was alarming to us, and we did some research on the National Museums of Kenya, which include the museum she conducted her studies at. We found that the Museums were founded by Richard Leakey, son of Louis Leakey (Kenya Museum Society). Louis Leakey was a paleoanthropologist and archaeologist who excavated the Olduvai Gorge in Africa, establishing a distinctly white, intellectual presence in the area (Biography.com). His family is recognized for its contributions to natural sciences. However, we found the fact that the National Museums of Kenya were founded on this basis of colonial history was problematic. That “sense of exclusion” that we heard about in our interview was indicative of deep underlying issues, which manifested themselves in the “segregated” space described in Kenya’s museums.

It was eye-opening to discover that the success or failure of museum exhibits to “recognize that culture is fluid and dynamic” and that “objects are alive in many ways” was a responsibility of the curator as well as the viewer. In our interview, we realized that viewers of exhibits were bringing their own prejudices and baggage to the exhibit, which works to reinforce misconceptions and internalized partialities. The viewer is therefore partially responsible for the experience they have at a museum, and their responsibility is not to rid themselves of all preconceived notions (which is impossible to do), but to “know the history of the where artifacts came from”.

Our interview also pointed towards hope for the future. We were reassured that museums were still relevant and useful, even as we are forced to question their practices. In order to reform museums, specifically natural history museums that are still organized to resurrect ideas from a Victorian era, “we can’t authoritatively present these cultures the way we have been” (Scott). To begin modifying museums that “conventionally didn’t take into account the audience,” the museum has to become more responsive to protests and voices outside of itself. The authority of the curator and their bias has to be countered with the inclusion of members of the culture being displayed. We learned that some museums have made efforts to engage the public by holding discussions and creating outreach programs for individuals to attend and contribute to. Museums that incorporate their audiences into the creation of exhibits can move towards a more progressive kind of institution, where contexts are included and visible to viewers. A museum exhibit is a “powerful” way to “see culture,” but “ideally, it’s from the perspective of the culture” that the exhibit is about. Nevertheless, museums are “a way to learn about the world” that have the ability to inform the public and celebrate culture. The key to improving the museum exhibit is to create “exhibits that are willing to raise more questions than offer answers...exhibits that question the visitor. Then you know you’re not walking into authoritative space. You’re given some agency and you can resist”.

Silence: The ever-present and multifaceted phenomenon

It is inevitable that someone’s voice will always be silenced - it is a matter of deciding whose is heard, and whose is not. In a society where some types of knowledge take authority over others the intellectual expert has been the intermediary from which the audience is fed. There have been many instances of stories being made to be spectacles, deprived of historical context as processed through the filter of the white anthropologist-- and yet, the outdated colonial ideologies continue to pervade. It is in this sense that silence is most virulently experienced. The latter is that of the sensory experience. Silence permeates most museum spaces in its anatomy, as a sterile space-- removed from its multidimensional aspects. We must not see art as objects-- art is alive. Experienced along with artwork, this view of silence has contributed to the static perception of art -- detached from the concept of culture as fluid and dynamic, changing in meaning over time. The literal sense of a lack of noise has given for a particular view of art, as music would change the perception of a piece. There is also the reflective aspect of silence, which promotes and spurs the contact zone with oneself, allowing for a space of self-confrontation and growth. Within ‘the space between’ verbal communication, one pauses to reflect and process more deeply what has occurred. In this way, museums act as venues for the discovery of oneself, and the world in which we live.

"Online Etymology Dictionary." Online Etymology Dictionary. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Dec. 2015.

"About Us." Kenya Museum Society. Kenya Museum Society, 28 Aug. 2011. Web. 07 Dec. 2015.

"Biography - Louis Leakey." Bio.com. A&E Networks Television, n.d. Web. 07 Dec. 2015.

Pusey, Grace. "Engaging "Backtalk": Decolonizing Bryn Mawr's African Art Collection." Web log post. Black at Bryn Mawr. N.p., 25 Feb. 2015. Web.

"Interview with Director of Museum Studies at Bryn Mawr College." Personal interview. 12 Nov. 2015.

Pratt, Mary Louise. "Arts of the Contact Zone." Profession (1991): 33-40.