April 18, 2021 - 04:59

Being the stereotype, when it comes to neurodivergence, has its privileges. There is, in some sense, an immediate validation; for example, there is more recognition and more understanding. In reality, though, most people are not the stereotype and whether one experiences a visible disability or an invisible disability, is the stereotype or is not, nearly all neurodivergent individuals experience intolerance, inaccessibility, and negative attributes associated with the identity. Neurodiversity exists on a spectrum. The current system, however, prefers categories, neat understandings of human existence. So what happens to people who do not fit into society’s categories?

Current understandings of what is considered neurodivergent are limited and everchanging. This is especially true when talking about presentations in women, non-binary or transgender individuals. Diagnosis of a neurodivergence in cis women is far less likely than it is in cis men, but very minimal has been formally discovered into why this may occur. There is also higher prevalence of neurodiversity in those that identify as non-binary, but still only hypotheses have speculated into the reasons. Why are there these discrepancies and how did they come to be? Are they truly because of biological differences? Differences in societal norms between genders? Or, is it something else? Further, how do current and past understandings of neufrodivergence affect current perceptions of it?

I hope to explore these questions further through this resource. The content will discuss why diagnosis is important, the history of diagnosis of some neurodevelopmental differences and how they have contributed to discrepancies in diagnosis between genders, as well as some ways gender is thought to interact with neurodivergence.

The category name “neurodevelopmental disorder” under the DSM is problematic because it implies that people who fall under its diagnosis have a problem that needs to be fixed. Thus, I will use the term “neurodevelopmental differences.”

This resource uses both “academic” resources and anecdotes from neurodivergent individuals (including students from Haverford College). Some neurodivergent individuals have even created educational resources through media like YouTube, Instagram, Blogs, and TikTok. For most of the history of disability, people first listened to the advice of scientists and healthcare professionals. However, it is clear that they have failed disabled people and have caused insurmountable harm and trauma. Disabled people are able to advocate what is least harmful for themselves, and other people do not need to dictate what is in their best interest. Therefore, it is necessary to amplify disabled voices, hear their stories of how they experience disability, and provide resources created by disabled people.

Most psychology studies use WEIRD populations, or Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic populations. In fact, about 80% of psychology studies use these types of populations, but make up only 12% of the world population (Azar). Despite this striking fact, little has been changed since the paper about WEIRD populations came out in 2010. This sampling bias implies current understandings of psychology are almost certainly not applicable to most individuals.

An upsurge of studies understanding the role of genetics and development of safer neuroimaging revealed that many neurodevelopmental differences have a genetic basis and that there are truly differences in the brain in between genders. However, these differences do not fully encapsulate the incidence versus true prevalence of neurodevelopmental differences between genders. Further, innate biological differences do not necessarily lead to development of a neurodevelopmental disorder, rather experiences of the individual can have influence as well.

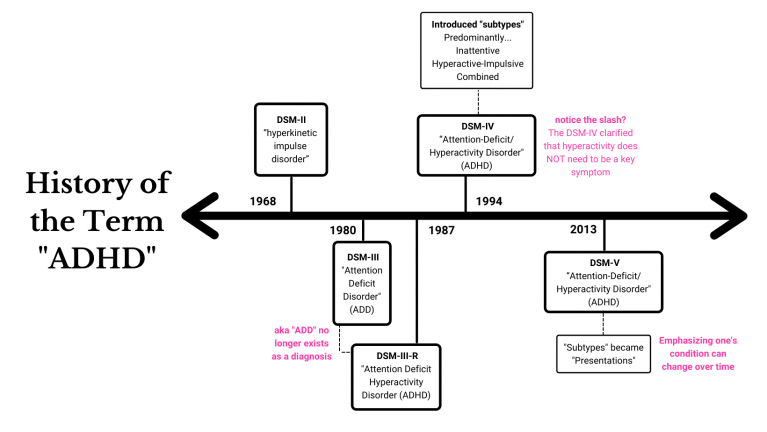

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is diagnosed in 5.4% of males, but 3.2% in females; however, the overall prevalence of ADHD is thought to be about equal in reality (“Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder”) . That said, it is believed that ¾ of women with ADHD are not diagnosed. ADHD was primarily studied in young boys who were hyperactive, which is likely to match with the current DSM criteria for predominantly hyperactive-impulsive ADHD. Furthermore, when creating diagnostic criteria and testing materials, clinicians based these tests off of this particular presentation in men. Additionally, clinicians are still unaware of changes to diagnostic criteria or have inaccurate beliefs about what different neurodevelopmental differences can actually look like in the population.

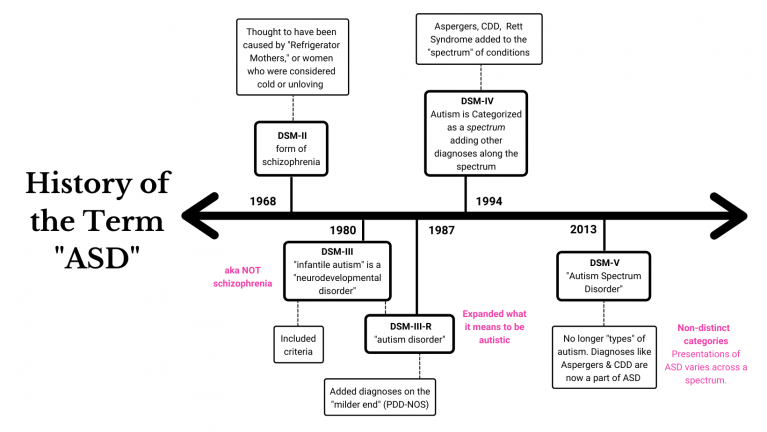

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Currently, ASD is diagnosed in 3 men for every 1 woman, though it is likely that this statistic may be still an overestimate of the true ratio (Zeliadt). Diagnostic criteria was created due to studying cis men with behaviors consistent with the current stereotype. Though symptoms for an individual might be the same between genders, like hyperfixations, the questions asked for diagnosis can be inherently gendered. For example, the question, “does your kid really focus on just playing with the wheels of a truck?” is inherently a masculine question and is not as likely to apply to non-male individuals (Layle). Similar to issues in diagnosis of ADHD, many clinicians still do not understand or know about alternative presentations of ASD and will deny diagnosis simply because of this.

Even When We Start to Get it Right, We Still Manage to Get it Wrong

Between these neurodevelopmental differences, the major commonality is that the history of these diagnoses is riddled with stigma, with validation for some, invalidation for others, and some populations will be more profoundly affected by these histories than others. Regardless of changes to diagnostic criteria, semantics, and theories, many inaccuracies of the past still manifest in the present to the point where even professionals get it wrong. It is also shown that even if women present in the stereotypically male way, they are still less likely than men to get diagnosed (“ADHD in Girls: How to Recognize the Symptoms“). Furthermore, women must have more significant behavioral issues than their male counterparts to get a diagnosis (Mowlem et al 765-773). This suggests that there is also a clinical bias preventing non-cis men from getting diagnosed and it is not merely a matter of awareness of the general population, but that it is ingrained throught throughout the system (Quinn and Madhoo).

Said by a Haverford Student with ADHD

Caption: "If me with the best opportunities and best help at a young age went under the radar for sixteen years, how is any other girl, trans or non-binary individual supposed to get diagnosed?"

Why is diagnosis important?

Diagnosis is helpful for treatment purposes-it’s an easy and fast way for clinicians to understand how best to help a person with a given problem. Misdiagnosis or not diagnosing at all has ranging consequences from ones that may be overall inconsequential to ones that are fatal. Those who are undiagnosed with a neurodivergence such as ADHD, for example, can experience severe depression, develop mood disorders or substance use disorder, get fired from a job, underperform, partake in risky activities, and other consequential problems (Hallowell).

For many, diagnosis often is a validating experience for many individuals. It gives an explanation for their behaviors and their struggles and also allows them to understand themselves better. Prior to diagnosis, many individuals experience self esteem issues, since the alternative is often some concoction of negative attributes to the individual such as laziness, carelessness, or coldness. It can also provide a sense of belonging, especially as many neurodivergent people share bonding experience as a part of a community.

Said by a Haverford Student with ADHD

Caption: "I absolutely resonate with the narrative that female socialization obscured the problem for many years-I wasn't hyiperactive but forgetful, had a rich internal world, would easily be distracted...I don't think being a woman affected my actual experience getting diagnosed, although I wonder if it contributed to my getting tested after high school rather than during, where the signs/symptoms were very present but I was functioning okay."

Comorbidities

Women commonly have comorbidities with mental illnesses or other types of neurodivergence. For example, ADHD is often comorbid with Dyslexia, Anxiety, or Depression in women. Additionally, women are often misdiagnosed with something else like depression or OCD before getting the correct one. Because studying neurodivergence presentations as a spectrum or across different genders is relatively new, clinicians have more trouble differentiating whether an issue is due to one diagnosis or another.

Masking

Women tend to camouflage their symptoms to seem more neurotypical by behaving in ways similar to their peers, something that men often have harder time doing. This is also known as masking. Masking can also include hiding symptoms by overcompensating. Women mask four times more frequently than men. While this may seem beneficial, it is a cognitively tiring process that can also be stressful or lead to more frequent meltdowns (Egeskov). Also, masking is developed as a learned trauma response from repetition of being rejected by their peers for being their authentic self (Cavanaugh). Additionally, identity formation can be more difficult as the true person underneath these masks can seem undifferentiable from the masks themselves (“Is Autistic Masking A Bad Thing?”).

Socially Acceptable Symptoms

The presentation of neurodivergence in cis men may be more apparent because their symptoms seem less socially acceptable. Paige Lytle, an autistic woman, also says that women’s symptoms can be completely opposite to men, describing how she acts overly social and engages in excessive eye contact, unlike what was originally thought to be characteristic of autistic individuals: lack of eye contact and difficulty or inability to be social (Layle). Further, some symptoms may be considered more unusual in males than they are in females, even if the symptoms are the same. For example, being more emotional or having meltdowns may be seen as more normal in women since women are seen as being emotional, whereas this behavior would stand out more in men since they are typically less emotional.

Said by a Haverford Student with ADHD

Caption: "For some reason, there's a fixation on how [neurodivergence] affects everyone else and not the actual person. Like 'high functioning' versus 'low functioning' is basically the degree to which a neurodivergent person makes NT people uncomfortable. But a 'high functioning' person might struggle as much or more than a 'low functioning' person."

Subtle Symptoms, Equally Hard

In cis men, it is far more common to have more disruptive symptoms. For example, neurodivergent boys are more likely to act out in school or interrupt class if they are struggling, whereas girls are more likely to behave well in class. The condition is the same, but its manifestation in how each individual presents themselves and their symptoms is different because gender is performative in nature. Some examples may be fidgeting or doodling instead of rocking or running around the classroom. Further, the presentation of neurodivergence in women may not be as obvious. Since characterizing a "disorder" is based on how much it affects the person's life, it makes it easier for a child who is actively disruptive or distressing to those around them to get referred for diagnosis first. However, women more commonly have internalizing symptoms like anxiety, depression, or emotional dysregulation (Quinn and Madhoo). Therefore, presentation does not indicate the severity or impact of neurodivergence on the individual.

Said by a Haverford Student with ADHD

Caption: "I think my queerness and the process of questioning my relationship to a strictly female gender has helped me embrace my neurodivergence. As a young girl, I was expected to be more composed, responsible, mature, high achieving, etc. than my male counterparts, and I wish[ed] my creative, wacky qualities had been more celebrated."

Neurodivergence is not limited to a few diagnoses. The most commonly talked about ones, however, are autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). This resource serves primarily to demonstrate the lack of knowledge both in the general population and in clinical settings, while also spreading awareness that gender interacts with how one presents their neurodivergence. Psychology is behind in many respects due to its emphasis on empirical research instead of considering the practicality and generalizability of the results. Of course, there are far more examples and intricacies of differences between genders in other neurodevelopmental differences, but there is so much we do not know about the effects of this aspect of identity. We are only really starting to understand this fact and even so, a lot of what is known is simply that differences exist but not precisely how or why. Despite changes made in the diagnostic process, the stereotypes and history of the past still exist and affect people today. Further, we need to move away from expecting that neurodivergence must look a certain way when humans are inherently complex with interactions of identities and experiences. As we become more aware of how science has failed so many individuals and start to change our priorities in how we attain knowledge, we can begin to truly understand our world and who lives in it.

References

“ADHD in Girls: How to Recognize the Symptoms.” YouTube, uploaded by How to ADHD, 13 April 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dmeE3qTJRUw&t=168s.

“Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder” National Institute of Mental Health ,https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd.shtml#:~:text=Prevalence%20of%20ADHD%20Among%20Adults,-Based%20on%20diagnostic&text=The%20overall%20prevalence%20of%20current,all%20other%20race%2Fethnicity%20groups.

Azar, B. “Are your findings ‘WEIRD’” American Psychological Association, vol.41, no. 5, 2010, http://www.apa.org/monitor/2010/05/weird.

Cavanaugh, Tiffany. “Both masking and unmasking is hard.” TikTok, uploaded by tiffanycavanaugh, 20 March 2021, https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMeHWafSd/.

Egeskov, Charlotte. “The Art of Masking: Autistic Women who Mask.” Tiimo, https://www.tiimoapp.com/blog/art-of-masking-women-with-autism/.

Hallowell, Edward. “The Downside of Undiagnosed Adult ADHD.” ADDitude, 12 January 2021, https://www.additudemag.com/undiagnosed-adult-adhd-diagnosis-symptoms/.

“Is Autistic Masking A Bad Thing?” YouTube, uploaded by Purple Ella, 23 October 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Ob_F6OwFVU.

Layle, Paige. “Autism in Girls Pt. 6.” TikTok, uploaded by paigelayle, 12 February 2021. https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMeHrbpDy/.

---”Autism in Girls Pt. 3.” TikTok, uploaded by paigelayle, 5 March 2021. https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMeHh94Kd/.

Mowlem, Florence, et al.”Do different factors influence whether girls versus boys meet ADHD diagnostic criteria? Sex differences among children with high ADHD symptoms“ vol. 272, 265-773, 2019 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6401208/.

Quinn, Patricia O. and Madhoo, Manisha. “A Review of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Women and Girls: Uncovering This Hidden Diagnosis” vol. 16 no. 3, 2014, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4195638/.

Zeliadt, Nicholette. “Autism’s sex ratio, explained.” Spectrum, 13 June 2018. https://www.spectrumnews.org/news/autisms-sex-ratio-explained/.

Comments

Social Media Content on Neurodivergence

Submitted by jcoletti on April 27, 2021 - 19:27 Permalink

Hey Lauren! I thought this was a great project and I really appreciated the ways you exemplified how neurodivergence presents and impacts different people differently and thought the way you incorporated peer interviews into your research was really great. I have also seen a lot of similar posts on TikTok and other social media about late and misdiagnoses for Autism and ADHD in afab people and BIPOC. For awhile I was also getting a lot of content about self-diagnosis, which from what I understand tends to be pretty widely accepted within neurodivergent communities-- which is important given all of the barriers to getting a diagnosis, and all of the miconception/misdiagnoses that you mention in your paper..... but I was also seeing some content that would go like: "If you do x thing, then you're probably autistic" or "if you do x thing you have ADHD" which might sometimes be relatable but was often really over-generalized. I suppose that's not really a coherent thought, but I was thinking about the balance between avoiding gatekeeping and also whether generalized/misinformation which could circulate on sites like TikTok could be harmful/invalidating (or if its just a relatively harmless symptom of mass content).

I definitely think it's a bit

Submitted by LaurenH on April 28, 2021 - 08:54 Permalink

I definitely think it's a bit of both! The gatekeeping is a huge issue especially as services are not given unless you have a formal diagnosis. Even with a formal diagnosis, some people will not believe the person. Of course, just because you experience symptoms of something doesn't mean you have it. However, it seems a lot of people seem to "know" they are neurodivergent and hence why they end up seeking diagnosis. Self-diagnosis can be iffy but probably a lot of the time it's correct. Being neurodivergent isn't exactly catchy or trendy and it has a lot of stigma, so if someone self-diagnoses themselves, they probably put a lot of time and research into it. Sometimes tiktok has some great information and sometimes it doesn't, like all things on the internet. The way I go about it is if the information is widely accepted by the neurodivergent community and/or clinicians have agreed that such thing does exist (ie have I seen a large amount of people talk about a similar thing or is it something that's just click-bait?). Sometimes, tiktok is looking for catchy things just like any other platform but I do think that there are people who are putting out good content that is widely supported.

I definitely think it's a bit

Submitted by LaurenH on April 28, 2021 - 08:54 Permalink

I definitely think it's a bit of both! The gatekeeping is a huge issue especially as services are not given unless you have a formal diagnosis. Even with a formal diagnosis, some people will not believe the person. Of course, just because you experience symptoms of something doesn't mean you have it. However, it seems a lot of people seem to "know" they are neurodivergent and hence why they end up seeking diagnosis. Self-diagnosis can be iffy but probably a lot of the time it's correct. Being neurodivergent isn't exactly catchy or trendy and it has a lot of stigma, so if someone self-diagnoses themselves, they probably put a lot of time and research into it. Sometimes tiktok has some great information and sometimes it doesn't, like all things on the internet. The way I go about it is if the information is widely accepted by the neurodivergent community and/or clinicians have agreed that such thing does exist (ie have I seen a large amount of people talk about a similar thing or is it something that's just click-bait?). Sometimes, tiktok is looking for catchy things just like any other platform but I do think that there are people who are putting out good content that is widely supported.