3/16/04:

Turning from Trees to Hamadryads to Humans

Reading....

A Very Short Introduction to Literary Theory

Where we left off...

Beginning with

Observations:

Then Adjusting the Focus:

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field

| And (on the other end of the scale....)

there's a tree that is more than fractal

| |

|

..which turns out to have a MUCH more interesting quality than "simple"

magnification:

Bethany's idea that thoughts/observations... are in an expanded form in our

heads. In order to transmit these thoughts ...to someone else, we have to ...contract our

ideas into ...words, and then speak them, they find their way into the ear of whomever

we are talking to, where they expand again, perhaps in the configuration in which they

were expanded in our heads, perhaps not....(expanded)IDEA >> (contracted)

LANGUAGE >> (expanded) IDEA [maybe same, maybe not]

let's look @ expansion/contraction/re-expansion into something DIFFERENT--

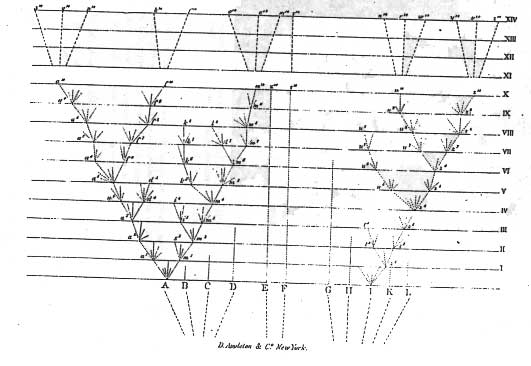

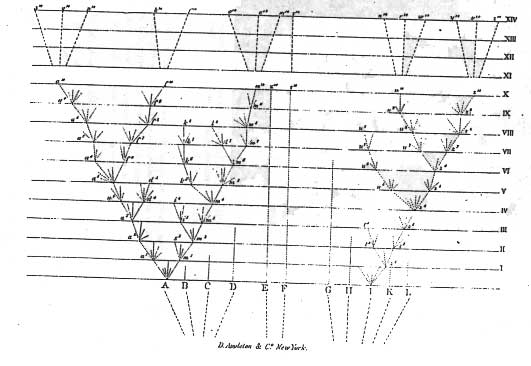

On/one of these branches (of Darwin's Tree)

are human beings:

From the Bryn

Mawr Alumnae Bulletin: Hilarie Johnston '76, Exhibitions Coordinator at

Haverford's Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, gave a September 19 gallery talk on her

paintings and bronze sculptures of hamadryads--mythological wood nymphs who

live their entire lives in trees--as a memorial to Cantor Fitzgerald employees who

died at the World Trade Center...."we're taking care of our dead insofar as we honor

the human figure in painting and sculpture....in our tradition ... the history of our human

ancestors is more important to us than a future paradise."

And yet, in each of these humans, there are culture-making capacities

which can--we're postulating, following the model of biological evolutionary theory--draw on what we've known and experienced to take us beyond what we have known

and experienced: to generate something new.

Turns out...we've got some good company

in using the concept of biological

evolution as a way of thinking about cultural evolution....

"Niles Eldredge:

Bursts of Cornets and Evolution, " New York Times (March 9, 2004) :

[With Stephen Jay Gould, Eldredge proposed] the theory of punctuated

equilibrium...that evolution occurs not as a gradual process but with long periods of

inactivity punctuated by short, sharp bursts of change.

...he hopes that by studying cornets he can find "a meta-theoretical, structural

framework for a general theory of material cultural evolution...." Generally, biologists

view evolution in strictly physical terms: how does a wing or a jaw change over time?

But ...Dr. Eldredge ...started thinking about evolution "as the transmission of patterns of

information."

Biologists classify organisms according to specific sets of characteristics or "vectors":

the shape of a wing, the length of a femur and so on. Dr. Eldredge has chosen 17

vectors that capture the essential anatomical features of the cornet. He has been

measuring his specimens and adding the information to his own database...using the

data to explore the way new ideas and designs spread through an instrument

population.

..the cornet, long a mainstay of any band, almost went extinct when Louis Armstrong

switched to a B-flat trumpet in the mid-20's. This pattern ..."strongly reminds one of the

situation between mammals and dinosaurs".... preliminary analysis of cornet evolution

suggests that material culture is also characterized by periods of relative inactivity

punctuated by intense bursts of change.

For Dr. Eldredge, one reason to study the evolution of cultural artifacts is to improve the

understanding of the interaction between what he calls genealogical and economic

hierarchies.... in material culture..."the marketplace is the ecosystem." In culture, as in

nature...the economic environment inevitably serves as an unpredictable force, driving

some species to extinction. Yet death is also the engine of innovation. As one group

dies, it is replaced by new forms.

This may actually prove to be a very generative way of thinking about the

classification of literary texts into genres....

but I want to start a little further back, and turn from the evolution of cornets

to the

(evolutionary?) practice of reading....

Rembrant, Old Woman Reading

(in Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam;

reproduced

@

Tigertail Virtual Museum ) |

from The Real-Estate Host |

So: what are these women up to? What's going on in these pictures?

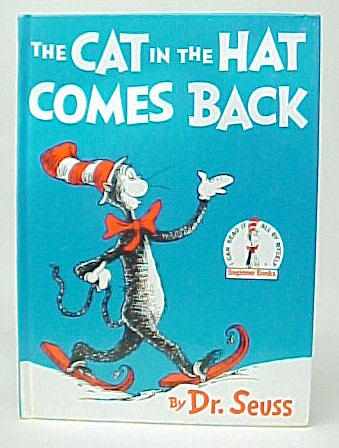

Let's give it a try: reading

- What is the meaning of this story?

- Why does the cat in the hat come back?

- What motivates his entrance into the text?

- What is his function in the text?

- What sense do you make of the pink stain? Of its eradication?

- Why will the cat in the hat be happy to come here again?

- What else is peculiar? striking? interesting to you in this story?

- (Have you read it/had it read to you before?

What are your memories of your earlier experiences?)

- What is the role of the alphabet in this tale?

- What is the role of the absent mother and father? (of their clothes, of their bed...?)

Possible Contexts for reading The Cat in the Hat Comes Back:

William Spaulding, director of the education division at Houghton Mifflin...asked Geisel

to write a story that used only a limited number of similar words, words recognizable by

a first grader....The success of "The Cat in the Hat" persuaded [Random House's

publisher, Bennett] Cerf to start a division...called Beginner Books....

The cat's improvisations with the objets trouves in the home he has invaded are

obviously an allegory for his creator's performance with the two hundred and twenty

arbitrary words he has been assigned by his publisher. The cat is a bricoleur. He has

no system--or, rather, his system is to have no system. He is compelled to make

meaning from whatever is there. He fails, the bricolage topples, the fish ends up in a

teapot; and this hint of semantic instability is expanded on in Dr. Seuss's most difficult

work (No. 26 all-time), "The Cat in the Hat Comes Back," published in 1958.

"The Cat in the Hat Comes Back" is the "Grammatology" of Dr. Seuss. It is a book about

language and structure, those Cold War obsessions....

These semiotic felines do exactly what a deconstructionist would predict: rather than

containing the stain, they disseminate it. Everything turns pink. The chain of

signification is interminable and, being interminable, indeterminate. The semantic

hygiene fetishized by the children is rudely violated; the "system" they imagined is

revealed to have no inside and no outside. It is revealed to be, in fact, just another

bricolage. The only way to end the spreading stain of semiosis is to unleash what,

since it cannot be named, must be termed "that which is not a sign." This is the Voom,

the final agent in the cat's arsenal. The Voom eradicates the pink queerness of a

textuality without boundaries; whiteness is back, though it is now the purity of absence--one wants to say (and, at this point, why not?) of abstinence. The association with

nuclear holocaust and its sterilizing fallout, wiping the planet clean of pinkness and

pinkos, is impossible to ignore. It is a strange story for teaching people how to read.

Why do our readings differ?

Where do those differences come from?

What is the range of allowable interpretation? How are its boundaries decided?

Is this an essentialist or a population-thinking-sort-of question?

Here's how Culler (in Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction ) describes

what we did:

Chapter 2: What is Literature?

(Well: What is Important for our Purposes):

- Literature is a paradoxical institution because to create literature is to write

according to existing formulas....but it is also to flout those conventions, to go beyond

them...an institution that lives by exposing and criticizing its own limits (41)

- Literature...is "cultural capital"...But literature cannot be reduced to this

conservative social function...literature is the noise of culture as well as its information.

It is an entropic force... (41)

- note above all the complexity and diversity of literature...the possibility of fictionally

exceeding what has previously been thought and written (40)

- a special structure of exemplarity...[that] simultaneously declines to define the

range or scope of that exemplarity (37)

4: Language, Meaning and Interpretation

- literature involves both properties of language and a special kind of attention

to language (55)

- Language is...both...the categories in which speakers are authorized to think--and

the site of its questioning or undoing (60)

- "reader-response criticism"...claims that the meaning of the text is the experience

of the reader...an interpretation of the work can be a story of that encounter...but the

story...depends upon...the reader's "horizon of expectations"...interpreting is a social

practice (63)

- Meaning is both what we understand and what in the text we try to understand...is

undecided, always to be decided, subject to decisions which are never irrevocable

(67)

- Meaning is context-bound....context is boundless; there is no determining in

advance what might count as relevant (67)

6: Narrative

- Essentially...a plot requires a transformation. There must be an initial situation,

a change ...and a resolution that marks the change as significant....there must be an

end relating back to the beginning...that indicates what has happened to the desire

that led to the events the story narrates (85)

- Plot is a way of shaping events to make them into a genuine story (86)

- narratives police...But narratives also provide a mode of social criticism (93)

7: Performative Language

The literary utterance...creates the state of affairs to which it refers... brings to

centre stage..an active,world-making use of language....acts of language that transform

the world, bringing into being the things that they name (97-98)

8: Identity, Identification, and the Subject

what drives theory...is the desire to see how far an idea...can go....Theory does not give

rise to harmonious solutions...but the prospect of further thought...theory is...an

ongoing project of thinking which does not end (122)

1: What is Theory?

(Well: What Is Important for our Purposes):

it is endless...an unbounded corpus of writing which is always being augmented...a

resource for constant upstagings....unmasterable...open ended...the condition of life

itself...the questioning of presumed results and the assumptions on which they are

based. The nature of theory is to undo...what you thought you knew, so the effects of

theory are not predictable (15-17).

SO: the production of literature (and the interpretations of its meanings--the results

of the encounter between text and reader, code and de-coder--which we call literary

theory) generate new accounts, new stories....

But how? What's the source of the new?

Here's how--in response to Anne's talk on The Relation between Numbers and

Narrative--Michael Tratner (BMC English Department Chair) described the ways

in which the seeking and identification of new patterns by literary scholars is

generative of new stories:

the outlier, in literary history, that matters is the one that somehow generates a

whole series of object similar to itself....a text that stands as simply 'different' from all the

others around it (in a period, in a genre...) is not very important unless it somehow

provides a pattern for repeated variants....for a surprising text to be readable to many

different minds, it must have some regularity, and for it to generate the desire to be

read by many persons, it has to provide something 'unusual' that is at the same time

repeatable...for a text to be both surprising and regular/original and influential it has to

interact not only with the norms for texts, but with the questions being debated about

texts at that moment: the surprise that is also regular or predictive....

A particularly useful version of this process, on the level of words, is traced by

Jonathan Culler in his introductory essay in On Puns: The Foundation of Letters (1987, pp. 1-16):

in both etymologies and puns...two similar sounding but distinct signifiers are

brought together, and the surface relationship between them invested with meaning

through the inventiveness and rhetorical skill of the writers....as in punning, the

interest of etymologies lies in the surprising coupling of different meanings....

Etymologies...give us respectable puns, endowing pun-like effects with the authority

of science....Etymologies show us what puns might be if taken seriously: illustrations

of the inherent instability of language and the power of uncodified linguistic relations

to produce meaning....etymologies, like puns,. ..are instances of speakers intervening

in language, articulating relations....intently or playfully working to reveal the

structures of language, motivating linguistic signs, allowing signifiers to affect

meaning by generating new connections....Puns present the disquieting spectacle

of a functioning of language where boundaries--between sounds, between sound

and letter, between meanings--count for less than one might imagine ....The relations

perceived by speakers affect meanings and thus the linguistic systems, which must

be taken to include the constant remotivation produced by impressions of connection

or similarity....

Not surprisingly, in both the realm of puns--relations between signs in a language at a

particular moment--and the realm of etymology--relations between signs from

different periods--there is no dearth of people anxious to control relations, to enforce

a distinction between real and false connections. Puns are an exemplary product of

language or mind....the exploration of formal resemblance to establish connections

of meaning seems the basic activity of literature; but this foundation...depends on

relations...is a function of practices of reading, forms of attention, and social

convention....

Punning frequently seems...a structural, connecting device...to offer the mind a

sense and an experience of an order that it does not master or comprehend....we are

urged to conceive an order.....Insofar as this is the goal or achievement of art, the pun

seems an exemplary agent....

In Ferdinand de Saussure's account, the linguistic system consists of ...signs

defined by their relations with one another. Emphasis on new punning relationships

disrupts the system.....If, as Saussure writes, the most precise characteristic of a

linguistic unit is to be what the others are not, what happens when it seems to be

another sign also?...we should ask whether in fact the language one speaks or writes

is not always exposed to the contamination of arbitrary signs by punning links....

Some examples from my section:

What do you get when you drop a piano down a mine shaft?

What do you get when you drop a piano onto a military base?

Why couldn't the pony talk?

What did the string say when the barman refused to serve him

(and he returned, a second time, all frazzled and frayed)?

Proposal: literary analysis is the making of new stories out of the stories

we have preserved; the most useful of those are continuously generative of what is

new. New stories are generated as we seek to identify a pattern that has a purpose, is

motivated....

Which is to say: we end where we began, with a tree that is more than

fractal:

expansive experience, contracted into a story, which is expanded

(by reading, by interpretation, by theory) into something new....

OR, as Samuel Beckett's Murphy (1952) says, "In the beginning was the pun."

SO: turning to Melville's Moby-Dick (and its many puns....)

let's see how this works:

From a Tribute Page @ Swarthmore College |

- Where did this story come from?

- Why does it take the shape it does?

- What meanings do we make of it?

- How do we make those meanings?

- Wherefrom do they arise?

- What motivates them?

- How context-bound are they?

- How do you determine what counts as relevant context?

- Of what further stories are this story and its meanings productive?

|

Return to Course

Homepage