Story of Evolution/Evolution of Stories

Bryn Mawr College

April 18, 2005

Entering the Parlor, Putting Your Oar Into A....

Discussion Interminable

| Where does the drama get its materials? From the "unending conversation" that is going on at the point in history when we are born. Imagine that you enter a parlor. You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before. You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him; another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you, to either the embarrassment or gratification of your opponent, depending upon the quality of your ally's assistance. However, the discussion is interminable. The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress.

Kenneth Burke, The Philosophy of Literary Form (110-110) From The Virtual Burkeian Parlor |  |

When last left off, the conversation in both the upstairs parlor and downstairs ballroom in English House was about whether or not Orlando was a text with "intention" (to satirize, for instance, the history of English literary forms). Is it a conscious parody, or a representation of the (unintending) unconscious @ play? Can it be both? Simultaneously? Or in quick alternation?

In an adjacent "room of her own" (her diary), Virginia Woolf herself said, I have written this book quicker than any: & it is all a joke; & yet gay & quick reading I think; a writers holiday....Orlando was the outcome of a perfectly definite, indeed overmastering impulse. I want fun. I want fantasy. I want (& this was serious) to give things their caricature value....The truth is I expect I began it as a joke and went on with it seriously. Hence it lacks some unity.... My notion is that there are offices to be discharged by talent for the relief of genius: meaning that one has the play side; the gift when it is mere gift, unapplied gift; & the gift when it is serious, going to business. And one relieves the other....

What amuses/pleases/intrigues me most about Woolf's novel is its refusal to choose between intent and lack thereof, its insistent "loopiness"

- between the serious and the playful,

- between meaning-making and meaning-refusing,

- between the singular and the multiple,

- between the shaped and the formless,

- between the metaphoric and the metonymic (in short!),

- between consciousness and the unconscious.

The constant shifts between these two poles in Orlando puts me in mind of what Sigmund Freud said to Salvador Dali in 1938 (ten years after Orlando was published): In the paintings of the old masters, one immediately looks for the unconscious whereas, when one looks at a surrealist painting, one immediately looks for the conscious.

[Metonymic interlude: What Dali was Doing]

"Just because I don't know what my paintings mean while I'm painting them," he contended, "doesn't mean that they're meaningless."

[Two metonymic asides to the metonymic aside]

Cf. my more associative/metonymic lectures w/ Paul's more directive/metaphoric ones?

Cf. public readings of humanists (preserving the beautiful surface, the careful metaphoric crafting of a text?),

vs. public performances of scientists (demonstrating a metonymic knowledge deep enough that it need not be read?)

Dali, "My Wife, Nude, Contemplating her Own Flesh Becoming Stairs, Three Vertebrae of a Column, Sky and Architecture" (1945)

Dali added, When I was five years old, I saw an insect that had been eaten by ants and of which nothing remaining but except the shell. Through the holes in its anatomy one could see the sky. Every time I wish to attain purity, I look at the sky through the flesh.

Dali would often pare a realistic representation...

Jean-François Millet, Angelus (1857-1859)

down to its "archeological" or "architectural" (=psychological/erotic) underpinings:

Dali, Archaeological Reminiscences of Millet's Angelus, 1933-35 |

Dali, Millet's Architectural Angelus, 1933 |

Although he also came, in time, to describe his shift from the iconography of the interior world surrealism represented to the iconography of the exterior world of physics:

Dali, The Station at Perpignan, 1965

All Dali paintings from Salvador Dali Biography Oil Painting Reproductions Art

Dali's paintings are unending revisions of one another.

Following his lead/inspiration, I want to make my last presentation in this course

less a meditation on what Orlando the text does, qua text,

than an invitation to us all to think about what comes next...

to think, in particular, about the evolution of literary forms into pictorial ones....

which means asking, more generally (again, following Dali),

Can Stories Evolve Through the Sharing of Pictures?

Annie: how remarkably pictorial this book is...pictures and photographs embedded within the text..turns fiction into fact....

Nada: I agree that the book is very pictorial...almost painfully descriptive....

How Necessary Is Language to the Evolution of Story?

To help us get at the answer to that question,

I want to pick up that "unending conversation" about the bipartite brain

...a little earlier, @ a moment last summer when Paul wrote a dead friend of his,

Descartes, to say

the elaborate architecture that makes thinking possible provides...the ability to reflect on and bring about changes in who we are.... So, here's the change I would like to make in "I think, therefore I am". I suggest we reword it as "I am, and I can think, therefore I can change who I am".....

Paul invited a wide range of his living friends to join him in Descartes' parlor, including one who emphasized the inherent and insistent social nature of thinking: "We Are, and We Can Talk, Therefore... " the self... within itself, porous and multiple...constantly takes others within itself...in that uncertain space where the outcome of the interchange is not predictable--and where we can together facilitate the revision of the world in which we all live.

Visitors to the parlor also included a watercolorist who, questioning this emphasis on revision, did a pair of paintings juxtaposing her visions of "Being vs. Becoming:

I ...acknowledge that thinking has a role in ...'becoming'....;

for me 'being' is more an 'in the moment kind of thing.'

The absence of any on-line response to these images led the painter to

ask,

are images somehow less conducive to interaction?.... and

Paul to

respond,

Are there differences between words and pictures as ways of thinking? Individually? Collectively? As ways of story sharing? Individually? Collectively?...Pictures are in general, I think, better than words at conveying feelings, intuitions, and .... things that can't (yet?) be put into words. And they are, in general, better at eliciting feelings/intuitions/etc in others....But they are less good for "comparing"....Words are an effort (imperfect as it often is) to express feelings/intuitions/etc...in a way that makes it possible to break apart some of the unity of feelings/intuitions/etc in a way that makes it possible to ask questions about and compare/contrast different parts of the whole. One of course pays a price for this, the story is never as rich as the feelings/intuitions/etc but it is, on the other hand, more "assailable", more subject to common testing.

Several more web pages were made, to explore this claim. In

"Something Quite Different From Dialogue":

The Accessibility and Assailability of Pictures, or How Art Works on Us, Rachel Grobstein said,

Indeed there is something especially in the nature of images and color (compared with words) which seems to suggest an exploration of associations, an opening of possibility, rather than the narrowing down of definition. With words, often one knows what one is trying to say, and the purpose of saying something is to define that idea, to fix it, to deliniate, to establish - to draw a very small box around the concept so that other people can understand (yes, to make the idea both accessible and assailable). But the very notion of purpose limits one's flexibility in exploring an idea. With images (and with words too, which Heidegger wrote about, but so much more easily with images) significations are so clearly not fixed; one can easily move between definitions, between ways of getting at or thinking about a particular thing. Instead of attempting to arrive at an idea, a definition, one can constantly suggest, without ever becoming fixed. And that's the sort of exploration I love in painting - the ability to start with a notion that is loosely or strictly defined...and see what comes of it in a way that takes myself by surprise.

What I'm saying is that it's much harder to escape the notion of "saying" something (no joke intended) when one is using language than when one is using pictures. And I like very much the idea of not trying to translate the very goopy mess of my impressions into something as close to universally understandable as possible, which is exactly what I try and do every time I open my mouth. I'd rather paint something that is meaningful to me (stress on the meaningful, rather than the meaning, because a painting hardly ever carries a specific meaning for me, again, a meaning that I could translate into words)....Insofar as I paint who I am, a "non static and non self-contained" thing...my painting is also not a static thing...let the painting serve as a departure point for whomever wants it for wherever they end up going.

There are further musings on (and intriguing pictorial representations of) related ideas @ On Friendship and the Power to Change: A Conversation in Images, which suggests that pictures change us not at the verbal level, but at the unconscious level, through the sharing of the feeling and emotion embedded in what we choose to [paint].

But--following the logic of this course to its (inevitable?) conclusion,

how revisable are the emotions pictures arouse in us?

How much evolution in story-telling do powerful pictures invite?

(Cf. Judith Butler ending her 4/14/05 talk in TGH on "Torture and the Ethics of Photography,"

by saying, of the photographs of Abu Ghraib: "I didn't want them with me."

An acknowledgement of the limited ability of words,

the limited power of analysis to contain the force of a picture?

"What is the sound of Abu Ghirad?")

There is a contemporary literary revision of Orlando,

Jacqueline Harpman's Orlanda:

Woolf's lyrical, fantastic novel Orlando, which a novelist has been reluctantly rereading for a class she must teach, proves to be the starting point for her self-awareness, as she realizes that it is not about the sexually ambiguous Vita Sackville-West, as literary historians would have it, but about the young Virginia Woolf--a "boy," with all the liberties of boyhood, who at puberty had to become a girl...She reports with wonder, amusement, and occasional condescension on the strange transformation experienced [when her] suppressed tomboy half splits off from her...and inhabits the body of a 20-year-old man.

But I'm more interested in exploring with you, today, what happens when the story is put into pictures; even more particularly, into a sequence of moving pictures:

"Orlando at the present time"

(What time is that?)

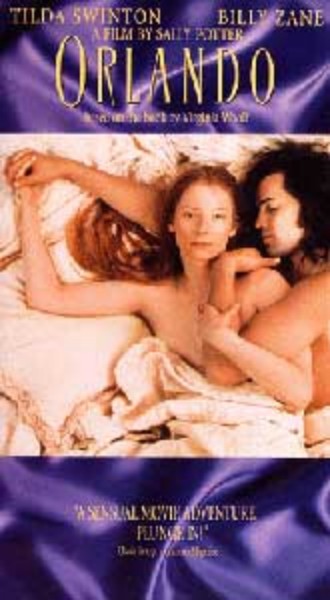

Let's see how this works, in the last ten minutes of Sally Potter's 1992 film Orlando.

Nuria Enciso, Turning the Gaze Around and Orlando

: The narrative is woven around what Orlando sees...to take account of women looking, on and off the screen....Faith must be placed in a new generation of filmmakers to only widen the points of view of and about women. The camera and/or the format is not the sculptor of passive femininity, but the person behind the camera. To quote Potter: "It's...time for women to take up our inheritance, an inheritance of a different kind. That's why the daughter is, at the end [of the film], playing with a little movie camera."

Sally Potter, Notes on the Adaptation of the Book Orlando (from Virginia Woolf Seminar): ...the film needed to engage with the energy of cinema. And although the book was already a distillation of 400 years of English history...the film needed to distill even further. The most immediate changes were structural. The storyline was simplified....The narrative also needed to be driven. Whereas the novel could withstand abstraction and arbitrariness (such as Orlando's change of sex) cinema is more pragmatic. There had to be reasons...to propel us along a journey....

Thus...Orlando's change of sex in the film is the result of his having reached a crisis point--a crisis of masculine identity. On the battlefield he looks death and destruction in the face and faces the challenge of kill or be killed. It is Orlando's unwillingness to conform to what is expected of him as a man that leads--within the logic of the film--to his change of sex. Later, of course, as a woman, Orlando finds that she cannot conform to what is expected of her as a female either, and makes a series of choices which leave her, unlike in the book, without marriage or property--and with a daughter, not a son.

Orlando is at its heart a story of loss--the loss of time as it passes--a meditation on the impermanence of love, power, and politics. I simply carried that logic through to include Orlando's loss of property and status in the 20th century....there is also an aspect which is worthy of celebration: the loss of privilege and status based on an outdated English class system....I tried to restore Orlando on film to a view more consistently detached and bitingly ironic in its view of the English class system and the colonial attitudes arising from it.

Other obvious changes from the book include...looks to the camera which were intended as an equivalent both of Virginia Woolf's direct addresses to her readers and to try to convert Virginia Woolf's literary wit into cinematic humor at which people could laugh out loud. Finally, the ending of the film needed to be brought into the present in order to remain true to Virginia Woolf's use of real-time at the end of the novel....Coming up to the present day meant acknowledging...the contraction of space through time reinvented by speed. But the film ends somewhere between heaven and earth in a place of ecstatic communion with the present moment.

In short, per Potter, the move from book to movie meant - distillation,

- simplification,

- pragmatism,

- propulsion,

- motivation,

- loss (and the celebration of loss?),

- the articulation of a political stance against property and privilege, and...

- presentism?

What might such changes indicate, more generally, about the continuing evolution of stories in filmic forms? What might they indicate about the relationship between the form of film to the nature of time? About the ways in which time gets represented in film?

Eileen: The end is not an end, it is a still life of Orlando and her lover...embracing at night, the time when reality shapeshifts freely...The power of memory and metaphor to distort... or truthfully, reveal reality as the thinly spread agreement it is, it smalleability and openness to constant, personal revision which is simultaneous and therefore varied beyond one person's comprehension.

Brittany: her immense talent as a writer...makes it *seem* like the last half of the novel spirals off into a hallucinogenic stream-of-consciousness....book ends on a single, identifiable moment in time...for one second, all of Orlando's internal "clocks" synchronized, and for just an instant, her multiple selves meshed completely into one.

Dali, Still Life Fast Moving

(For further exploration of the artistic unconscious,

see American Visionary Art Museum, Baltimore.)

| Course Home Page

| Science in Culture

| Serendip Home |

Send us your comments at Serendip

© by Serendip 1994-

- Last Modified:

Wednesday, 02-May-2018 10:51:47 CDT