|

Part 2: Section 3 |

|||

|

Prozac, Empathy, and Brain Systems |

|||

| I would like to start out with a quote from Peter Kramer’s Listening to Prozac | |||

|

|||

| What

Peter Kramer did is somewhat remarkable considering his professional

training as a traditional analyst coming from an era of psychoanalysts

who are preoccupied with details of chemical interactions, neurotransmission,

and genetic predispositions. He actually “listened” to his observations

of patients taking Prozac. That is, through “talk therapy” he was able

to probe something traditional scientists often shun from or simply

reduce to biological materialism…the depth of the human “soul.” |

|||

| He

noticed that most of the people on Prozac became “better than well.”

The pill made them want to talk about their experiences. In general it

seemed to reduce separation anxiety by increasing empathy. |

|||

|

|||

| Kramer

noticed that traditional explanations based on animal models and chemical

levels were misleading his conception of the self. For instance, Kramer

once had a patient in his office who after he has been given the pills

was quite anxious. At first, Kramer attributed this to a common side

effect of Prozac that includes nervousness or anxiety in the first couple

of weeks. However, when he learned that the patient did not take the

pills, he started to “listen” for

the roots of the anxiety that seems to come from something deeper. Basically,

the explanation for our capacity to feel and vicariously experience the

feelings of another human being has to cover more ground that what the

chemistry is willing to offer. |

|||

| Kramer

hypothesized that Prozac is affecting certain AREAS OF THE BRAIN concerned

with “feelings of abandonment.”That

is, it is not simply a matter of neurotransmitter and other chemical involvement

but a matter of a rather malleable material (think of it as a brain area)

through which the emergence of something deeper occurs.

I want to make sure that

I do not misuse this word in a traditional sense. What I mean by “the

soul” is the broader concepts such as anxiety and feelings that are

not just a result of the chemical interactions. Think back to the story

of the patient I alluded to in the last paragraph. The patients “self”

was in trouble and the way to understand that was to look at

why it was so. We had to look at “the

aboutness” of the problem. |

|||

| It is

important to note that the idea of a particular brain area processing

a particular set of feelings concerned with, say interpersonal relations

(which includes the feelings presented by empathy), is not so farfetched

in neurobiology research. I already alluded to it in the section on

Pheromones

. That is, in the case of

mating behavior of hamsters, there seemed to be brain centers that can

be stimulated by chemicals such as pheromones or by learned

behaviors, such as in the case of male hamsters who had previous encounters

with a female. However, that is more of a speculation. More solid support

for the notion of brain centers comes from the studies of cocaine effects

on the brain. |

|||

|

COCAINE AND BRAIN SYSTEMS |

|||

|

|

|||

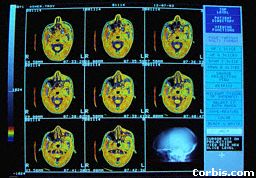

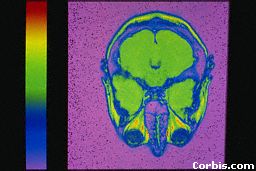

| Most of the progress in this area is actually fairly resent. In the 1990’s brain imaging technology called functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) was developed. The usefulness of this technique is that it lets scientists visualize actual AREAS of the brain hypothesized to be active during a particular emotion, say the “rush” or “craving” aspects of drug abuse. Through fMRI studies (which show increased nerve activity in areas of brain when subject is rating their feelings as rush or craving) of cocaine addicts, scientists determined that certain parts of the brain are responsible for rush versus craving feelings associated with cocaine use. For details of the study go to http://www.drugabuse.gov/NIDA_Notes/NNVol13N5/Cocaine.html . | |||

| Also, it was discovered that brain systems, which are now termed Dopamine systems, are actual brain areas that are stimulated by certain drugs such as cocaine and heroine. From here came the hypothesis that these brain systems are responsible for information processing with regards to stimulus associated with pleasurable input or act. | |||

CONCLUSIONS |

|||

|

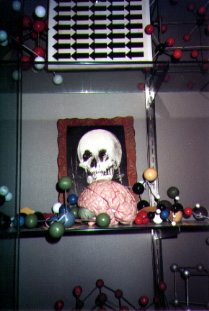

Photo by Rachel Berman |

|||

| Kramer’s thesis is a wonderful starting hypothesis that is supported by some current scientific findings in brain research, particularly in cocaine usage. It thus adds to our chemical model to a great extent. Also, it is testable in some ways. That is, if we assume that there actually exist specific brain areas concerned with “feelings of abandonment” and interpersonal relations in general, a good experiment would be to examine cases when a person is incapable of having such relations. This is the subject of the next part in which I examine Autism . | |||

| The cover of Peter Kramer's book shows a man actually “taking off” his face off leaving behind a blank surface in its place. Questions such as what is the real self come into play here. I am not about to even try to answer such question, but at this point I can based on our discussion so far HYPOTHESIZE that | |||

|

THERE ARE BRAIN CENTERS CONCERNED WITH INTERPERSONAL RELATIONS |

|||

| What happens when these are damaged or not developed is the subject of Part 3 . | |||

| LINKS on BRAIN SYSTEMS and COCAINE | |||

|

Cocaine Activates Different Brain Regions

for Rush Versus Craving Center for Neural Bases of Cognition The Use of Cocaine Causes Brain Lesions Monkeys on Cocaine Can Survive Repeated Brain

Probes New Brain Studies Yield Insights Into Cocaine

Binging Cocaine Dependence And Withdrawal: Neuroadaptive

Changes In Brain Cocaine, Speed Changes Brain In Rats |

|||