|

INTRODUCTION

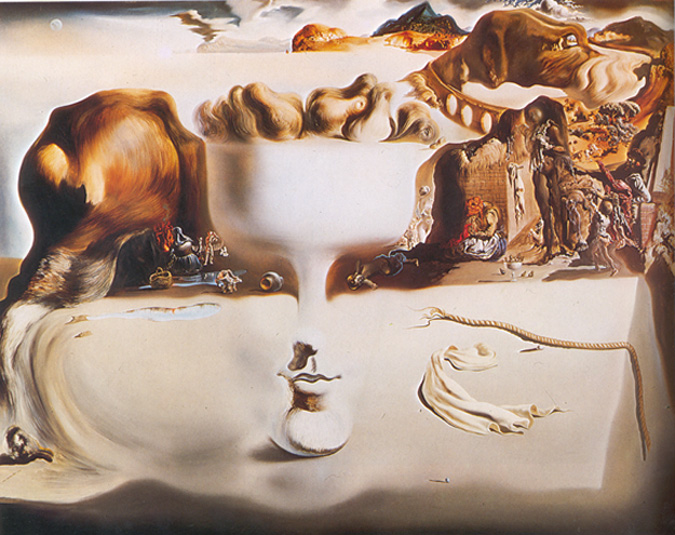

Photo by Rachel Berman |

|||||

| There was a time not too long ago when I thought that the universe, and the foundations of behavior lied in the most fundamental matter from which it was comprised. Studying chemistry meant getting a step closer to understanding the universe. However, during my college years I started to go through a sort of an evolution of the self. | |||||

| The first day in my Neurobiology and Behavior class, my professor held up a brain and asked what we thought of the idea that brain and behavior are equal. Many spoke of religious beliefs and the notions of the mind and the soul, which cannot be explained by the physical, which is the brain. I remember feeling a sense of superiority; I was a true scientist, I knew better. In fact, this was my first response entry written in that class: | |||||

|

|||||

|

Photo by Rachel Berman |

|||||

| Its funny I mentioned love when I wrote this entry because almost three years after it, this was the very topic I was preoccupied with. Whether it was because I thought that I experienced it and lost it or because my intellectual life as a chemist was boring me, I had a strange feeling of utter emptiness. I was looking for something...something that would have meaning, something that would inspire me. | |||||

| The last thing in my life which inspired me was love. So perhaps by learning about it I could somehow rekindle that inspiration or make sense of what happened to me. The first thing which probably emerged was my training as a chemist. I was going to define the system in question and then study it. My advisor, , gave the best characterization of this “syndrome.” He called it “intellectual schizophrenia.” I definitely had two opposite sides to my intellectual inquiries. One had to do with what I thought was proper science, the inquiry concerned with the “right” answer. That is, anything a scientist says should be possible to rephrase as a summary of well defined observations. The other part of me was concerned with concepts which mattered to me. These were abstract concepts such as love and art. What I had to do for the first time in my life was to try to put the two together. | |||||

|

Photo by Rachel Berman |

|||||

| I started out reading all sorts of ideas about love, and there are so much! Poets, neurobiologists, and just about any person on the internet had something to say on this topic. I tried to narrow my search by looking at articles written by PhD’s. Propositions stating that “The cerebellum [is] the principle structure involved in mediation of an abnormal social behaviors of mother deprived monkeys…” appealed to me. However, I realized two things during my primary endeavors. First, just because someone has a Ph.D. may not mean much about the type of research performed. Secondly, anyone identifying a certain brain structure as the only determinate of a complex behavior is not considering the context in which that behavior emerges. | |||||

| The first step to unifying the two sides of my "intellectual schizophrenia" was to realize that love is a human concept, a characteristic of a human language. When you give something a noun it carries the implication that it is a unitary thing. This is the idea expressed in the opening poem . One reason science is able to shed light on things is because it breaks them down. What I needed to do was to take the concept apart. I had to rephrase my original question, which frankly now seems rather absurd: What is love? | |||||

| If I was to be scientific about this matter at all, I had to break it apart and learn about the pieces. So the way to make sense of it was not to take it in isolation but figure out where it sits in a broader context., Then try to make sense of the broader context. Thus, the goal was to find small questions using “systems” in which pieces of the concept of love emerge. These systems were not limited. In fact, the first I choose was drugs. I was reading an article on Ecstasy , a drug which produces various feelings associated with love, and decided to study the drug itself. Next, I had to figure out what was solid in the chosen systems…maybe then I could form some conclusions and relate them back to the broader context of this ...whatever that may be. | |||||

| There are essentially six parts to this project: | |||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||