Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Blogs

Old City

This summer I participated in “Tri-Co”, a program where Swarthmore, Haverford, and Bryn Mawr students discuss social justice, equity, and diversity. During one caucus we touched on the Norristown High Speed Line and how Bi-Co students often refer to it as “sketchy”. What was it about the train that made students afraid or uncomfortable and what exactly did they mean by “sketchy”? The upperclassman agreed that it attracted more minorities and working class people rather than the business men and women that typically use the R5. When I boarded the train on Saturday, I found it to be like any typical New York City train cart. There were a larger range of people on board which included large families, construction workers, and students.

After we transferred to the Market-Frankford line, however, I could see how the crowd might make students uncomfortable. There were several homeless people on board that tried to strike up conversations with the people around them. One man in front of me continually yelled at every passenger that carried a bottled drink, turned around in his seat and stared my group and I down, and muttered profanities under his breath. Being raised in New York definitely taught me to put my guard up and expect the worse when in these situations. Although the homeless people in New York aren’t typically as aggressive, I’m used to receiving attention from them.

Breaking the Rules

Jessica Bernal

ESEM-Play in The City

Breaking the Rules

If I followed every rule to the dot growing up, then I wouldn’t have learned a thing in life. As mentioned before, instead of working on math in third grade, I watched movies and I didn’t turn out so bad, so they say.

If I base my experience of Spring Gardens in Philadelphia to what play should be according to Costikyan, “games are by their definition competitive in that they always have an end point- a winning or losing state” (Flanagan, 7) then no I didn’t “play critically” into the city. But playing critically is not about having a winning or losing state or following the rules, in my perspective, playing is about breaking the rules and as Flanagan states, “Critical play means to create or occupy play environments and activities that represent one or more questions about aspects of human life.” (pg.6)

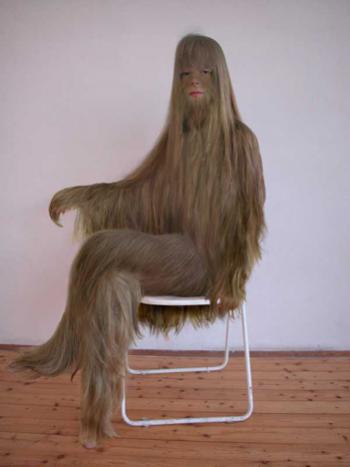

The Duality of the Gaze: An Exploration of the Beauty and Shame Found Found in the Female Body

In 2009, I visited an art exhibition at the Austrian Cultural Forum New York, titled “The Seen and Hidden: [Dis]Covering the Veil.” The show created a clash of western and eastern cultures in order to display the controversial interpretations of what it means to be covered, objectified, and sexualized in the preconceived notions of Arabic and Islamic cultures. The pieces in the show invoked a vivid sense of both frustration and mockery at the overall confusion and misunderstanding found across the globe, which has ultimately resulted from the potent duality of the gaze.

Critically Playing in the City

This trip into Philly was full of change. This helped me “critically play” because it was different from my normal routine. Mary Flanagan, in the introduction to her book Critical Play, defines play as “central to human and animal life; is generally a voluntary act; offers pleasure in its own right (and by its own rides); is mentally or physically challenging; and is separated from reality” (Flanagan 5). Some aspects of this trip that were different from my normal day include the food, the atmosphere, and the transportation.

My average day is spent in classes, at a desk studying, or eating the dining halls’ consistent but decent cuisine. The occasional escape from this normalcy is treasured. One very easy way to break this routine is through food. Although Bryn Mawr’s food is delicious, trying new flavors and textures helps interrupt the monotony of the school year. For dietary exploration, I turned to the city of Philadelphia.

Mushroom Man

Perspective is everything. When you throw out your trash, you don’t see it as art or something to play with. Those glass bottles you’re about to throw out are probably going to go to the landfills, lost within other glass bottles or dirty paper towels. That broken bike you can’t trust anymore will also make the trip to the landfill, as will those outdated wall tiles that once decorated your home. Isaiah Zagar sees the glass bottles, broken bicycle, and wall tiles as art. He sees them as parts of his art. One man’s trash is another man’s artwork. The Magic Gardens in Philadelphia show us that our trash can be beautiful; it isn’t just stinky junk that we don’t want anymore. When you throw out your trash, you don’t think that it can be a part of a mosaic that people pay money to visit.

play out of expectation

I thought play is an act that mainly brings me happiness and joy before; however, after this trip, I found playing is not always that enjoyable. On the other hand, sometimes, it can bring me both the excitement and uncomfortable feeling, both nervousness and surprise.

In Flanagan’s work, she regards playing as a media to express subversive views- to break the rules. In the trips before, I never intentionally try to feel this. In other words, I just see the subversion in the mosaics by Zagar- the unorthodox expression of art with broken trashes and frameless piece of work. However, I never find the subversion in my playing in the city in those trips. The trip to old city and Chestnut Street this time leaves me an unforgettable and mixed feelings and thoughts.

To Subvert With Pomegranate (2)

Phoenix

MLord

Play in the City 028

Sunday, October 6, 2013

To Subvert With Pomegranate

As a player in the city, I “explore what is permissible and what pushes at that boundary between rules and expectations” (Flanagan 13). For a long time now, I have understood instinctively that art, to me, is a way of surprising people. The first person who put this sensation into words was Dorothy Allison in her essay, "This is Our World." Allison described art as a way to challenge and to cause people to think about the ideas that they prefer to shove aside and pretend don't exist. My reaction to this was an intense sense of "I'm not the only one." According to Mary Flanagan, not only am I not the only one, I come from a long line of artists who see art as their tool to shock and surprise—their instrument of Duchamp’s “spirit of revolt” (Flanagan 3, 10).

I take pictures of pineapples in ordinary places. The juxtaposition between the pineapple, a most peculiar looking object that has become normal, with a familiar location, reminds the viewer of the oddity a pineapple really is. A pineapple in bed, on a shelf next to books, answering the telephone, all have been ways I have played with a pineapple. Subversion, according to Flanagan, is the upending of a paradigm—but one must know what one is trying to upend. I was not sure, then, what I was trying to subvert or what I was trying to say, only that I wished for viewers to wake up to the real world if only for a minute.

What Is Art?

Samantha Plate

Play In The City

10/06/2013

What Is Art?

In Mary Flanagan’s book Critical Play, she tries to define play through art. She associates play with art because they both “manifest critical thinking” (Flanagan 3). She believes artists use play in their work, often in subversive ways. While in Philadelphia this weekend I experienced a lot of art. This made me think of Flanagan and how art is connected to play. Last week I examined one of Flanagan’s definitions of play and how it fit with what I saw. This week I viewed my experience of Philadelphia through her view of art. Flanagan makes a few statements about art and its playful and subversive qualities to help define it. Flanagan first quotes Marcel Duchamp saying "in art there is no such thing as perfection" (Flanagan 3). She believes there is a "call for innovation" in the art world and subsequently in play. When it comes to defining what an artist is, she uses "’making’ for ‘making's sake’" (rather than for some arbitrary reason like money) as a qualification (Flanagan 4). Flanagan also discusses the subversive nature of art. It made me question if art has to be subversive to be playful or vice versa? Flanagan looks at Antonio Negri and determines that subversion is “a creative act rather than a destructive act” (Flanagan 11). Subversion is all about breaking rules and so naturally both play and art are conducive to subversion, but must they be subversive?

Tag-A-Long

|

|

Philadelphia, 1967: Darryl McCray begins painting his nickname, “Cornbread”, on the streets of North Philadelphia to get a girl’s attention.

Philadelphia, 1984: The Philadelphia Anti-Graffiti Network (PAGN) is established to combat vandalism.

Philadelphia, 2013: The battle over graffiti rages on.

Philadelphia’s First Friday is an art festival of sorts that Old City organizes on the first Friday of every month. Rain or shine, fine art galleries between Front and Third, and Market and Vine streets can be found with open doors welcoming world-weary Philadelphians into their wine-scented interiors.

Figuring It Out: Web Event 1

Trigger warning: sexual assault

In Neil Gaiman’s The Doll House, women are cats. Women are a lot of things in this graphic novel: protagonists, foils, stupid, smart, slut-shamed, and presented as tropes. Amongst the same old nonsense, though, Gaiman uses metonymy to describe women, while I, reading the book, was also using something to symbolize something about myself, also a woman.

Throughout The Doll House, Gaiman has a lot of people “playing” with women. The book is scattered with references to women as things that someone can play with; toying with them like playing with a cat. The women are props in his book to play out a larger story, and within the big, sweeping narrative of dreaming and waking, the women are played with even more. They are made into sex objects to be manipulated with like they are as inhuman as cats (pausing only to make the connection between “pussies” and “cats”). When serial killers in Part V of the novel meet and talk about their experiences, one goes on about starting off with “pussies” and cutting off their heads—a description that could easily reference cats or vulvas.

Gaiman draws on symbolism to make his novel more detailed on the micro-level. It fleshes out dialogue and character interaction with a running pun that references patriarchal oppression and modern day conflict. Gaiman, the author, uses symbolism in his writing. I, a student, signal sometimes explicit details about myself.