Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Reply to comment

California EPA

I have never felt the strength of the Bryn Mawr alumnae network as acutely as I felt it while doing an internships at the California EPA with a Bryn Mawr alumna, a biologist working at the Air Resources Board (ARB). As somebody interested in public health, I saw many obvious links to topics I had already been interested in, like increased rates of childhood asthma in urban areas. The ARB is in charge of air pollution generally, so they do focus on issues like asthma, but they are the only division officially working to reduce California’s greenhouse gas emissions, and thus do a lot of research on climate change. I already cared about climate change, but had little academic background or understanding, so it felt a little bit like I was being thrust into a new world. I ended up working on the “State Implementation Plan” on regional haze for the federal EPA, and learned more about the science and politics of haze than I ever imagined.

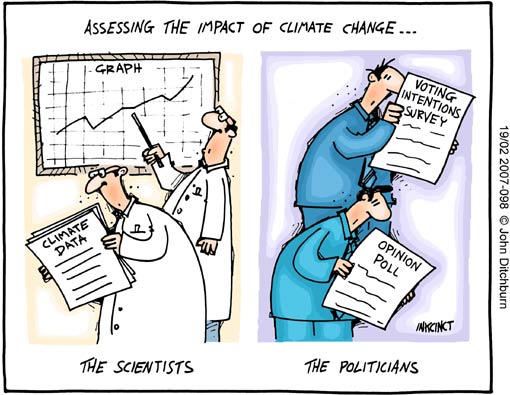

Before I went to Sacramento, I was given piles of information on haze, and learned about the specific emissions contributing to California’s problem. Once I got there, however, I quickly realized that the scientists working at Cal/EPA are just as much professional politicians as they are climatologists or astrophysicists or biologists. An already complex atmospheric concern is clouded even further by the many “stakeholders” throwing their biased opinions at the policy. Climate scientist Spencer Weart brings up the question of whether or not scientists are obligated to engage in politics or inform the public of their findings. I don’t think that they necessarily need to – I think that there is merit in having a career devoted to research, free from additional bureaucratic distractions. I do, however, find it crucial that there are scientists partaking in the decision making whenever climate policy is being determined. What I saw at Cal/EPA was that scientists had a difficult time crosseing the thin line from advocating to politicking.

During one of my first days at Cal/EPA, I sat in on a meeting about a Valero refinery in Benecia, whose sulfur oxide emissions are significantly above the legal limit. (Which is on public record, so no corporate secrets are being broken.) The science-based answer is simple – they need to build new furnaces that will lower the emissions being produced. But, instead, what was being discussed was Valero’s consent-decree with the Federal Bureau of Land Management – could California hold them to an even higher standard without facing litigation? Valero needs to meet “best available retrofit technology”-level controls, but those numbers are partially based on cost-effectiveness. Would the new furnaces cost as much as Valero claims? California has agreements with neighboring states about these kinds of point sources – would Nevada feel threatened if the regulations were too stringent? The scientific data about the public health and visibility effects of sulfur emissions is clear, but that didn’t matter – politics did.

In the short amount of time I was at Cal/EPA, I saw how quickly exhaustion can come, and felt how inconsequential scientific advancement can seem when it has no purpose besides the academic. I think that scientists engaged in policy need to garner enough “concerned citizens” to become their own special interest – stakeholders who get to make comments at public hearings. Legislation that is supposedly based on scientific data sometimes becomes a little bit stained with each additional hand that touches it. I see similar issues in the public health work I do today, which feels worlds away from the EPA, but experiences similar roadblocks. Scientific data can be available (HIV vaccines hold promise!), but government funding often follows the whims of private donors, not the data. In the end, the Regional Haze plan got passed after I left, and I felt like there was a win for science over money. I sometimes worry that I’ve become too pessimistic about policy making processes, and it’s nice to remember that – at least in California – it’s not always so bad. I also realize that as I become a researcher myself it will be important to think about my findings not only in terms of their scientific importance, but also their policy implications. And then, I hope, I'll fight for those policies.