Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Reply to comment

Crafting Sustainable Teaching Practices: ASLE 2013

ASLE 2013 Conference on Changing Nature, Lawrence, Kansas

Concurrent Session 4, Thursday, May 30, 8:30-10:00 AM

Stream: Ecopedagogy

Crafting Sustainable Teaching Practices:

Respecting and Relying on the Eco-System

Sophia Abbot, Anne Dalke, Jody Cohen and Chandrea Peng

Bryn Mawr College

Bruno Del Favero, "Landscape with River and Exotic Church,"

in "Great and Mighty Things," the current exhibit of

"Outsider Art" @ the Philadelphia Art Museum

I. Anne’s introduction

Good morning! Thank you for joining us so early in the day!

We’d like to begin our conversation in silence, with some visuals--

does everyone have a pencil and paper? Or a computer for typing...?

Would you write for a few minutes, please, about what you are seeing?

This can be “straight” description--the particularities of what you are seeing (color, shape, size),

or it could have an affective dimension--how does it make you feel, to look @ these images?

What do you see here?

What is like-or-different about this image?

And this one...?

...and this?

....this?

And finally...this?

So...what did we see?

What similarities do you notice among these images?

What differences?

In what ways are our sight lines congruous?

In what ways do they diverge from one another?

Let me give you a little context for what we are see/sawing....

(the sequence of seven images you saw were of

* the walls of an old graveyard on the margins of our campus,

* a cloister @ the center of that campus,

* the main entrance to the campus,

* the walls of Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia, now closed,

* the entrance to The Cannery, a minimum security prison for women,

(right next to Holmesburg), where we held classes last fall; and

* the walls to The Magic Garden, a visionary art environment in South Philadelphia.

These images should help you to locate us. We hail from Philadelphia--or rather, nearby.

We join you this morning as four colleagues from Bryn Mawr, a small women’s liberal arts college just outside of the city. Three years ago, Bryn Mawr initiated a new program (in which we are all enthusiastic participants) called the 360°, in which a cohort of students takes a cluster of courses together, over the course of a semester (or a year). They learn to integrate distinct disciplinary perspectives on a focused topic, engage in non-traditional classroom experiences, and then share what they have learned with the Bryn Mawr community, and beyond. As you might imagine, this is a structure that is very compatible with Environmental Studies, and a number of the clusters have been in that area: one on Perspectives on Sustainability was designed colleagues in education (--that would be Jody), mathematics, and urban design; another, on Renewable Energy, was co-taught by a chemist and geologist); a third, Transforming the Legacy of Oil, included courses in Economics, History and the Growth and Structure of Cities.

Jody (who is in the Education Program) and I (who am in English and Gender Studies) have served on the 360 ° Steering Committee since its inception, and have each taught in the program; Chandrea and Sophia (who have each designed Independent Majors in Education), have also taken several 360°s, and are now serving as our student consultants in a new one, which we are co-designing with an economist and a visual artist who makes ecological sculpture, drawing and photography. This new cluster is called Ecological Literacy: Education, Expression, Economics, and we will offer it next spring.

Our plan for this morning, however, is not to talk specifically about that project but rather, more generally, about a pedagogical orientation which, we posit, is both ecological and sustainable, in the very largest sense....we want to invite you to think, ecologically, about the classroom. We want to invite you to think about the classroom as an eco-system: complex, networked--and unpredictable.

In order to do that, we will focus not on our new eco-360°, which is so explicitly about things ecological, but on another 360° the four of us did together last fall, called Women in Walled Communities. In this cluster, we examined the constraints and agency of individual actors in the institutional settings of women's colleges and prisons. Over the course of that semester, the boundaries between “inside” and “outside” became, as you might imagine, very porous. We found ourselves dancing between the containable and the uncontainable, noticing how every attempt to control what emerged provoked what is uncontrollable. What we learned together that semester--and want to talk with you about now--is our emergent view of the classroom, and of the environment in which it is situated--that is, the whole world--as fundamentally uncontainable.

Rob Nixon anticipated our argument, yesterday morning, when he spoke about the spread of gated communities, and the construction of ever high walls (such as the plan to build a sea wall around lower Manhatten...bouncing the ways to Far Rockaway....?).

When Jody and I began co-teaching together, several years ago, we started by acknowledging the limits--of time, of human energy, of space, money and new ideas: the very real material-and-mental constraints which often make it seem that we are working within a system that is running down. Our initial plan, in sketching out a design for “sustainable teaching,” was to “take” more time, and “create” more space: we would search for naps, practice meditation, remind one another to slow down, breathe deeply….

In the process of teaching several courses together, however, presenting several conference workshops, and writing about our experiences, we found a complement to our (understandable!) desire to set limits, in the counterintuitive realization that the world in which we operate as teachers and as human beings is an infinitely capacious one. We had the experience of relying on that which we do not know, on the unending supply of the surprising, which lies hidden in the complexities of our students’ unconscious, and in our own.

And so we are here, this morning, to argue that limitlessness is a richer way to think about sustainable pedagogy than is seeking new and better boundaries. Or, @ least, that every boundary will construct will inevitably be transgressed. We need containers--the classroom is a container--but they will never be able to hold all that emerges there....

II. Chandrea’s stories

I remember when a classmate gushed to me about how exciting this 360 would be and my lukewarm reaction. I knew it’d be great because I trusted and liked the professors who would be leading the 360, but I was less than excited about the idea of taking the same three classes with the same 18 people. I wanted to spend my semester getting to know lots of other people in a bunch of other classes. Looking back, I realize that I do, in fact, do my best learning in smaller groups, but I also think deep down I had this fear of being in such an intimate classroom setting. I was scared that my classmates would see that I didn’t have my shit together, and I was scared they were going to judge me for it. In fact, It wasn’t actually that I wanted to get to know a ton of other people, it was that I wanted to be in a class of 50 people where I could sit in the back and never say a word the whole entire semester. I was prepared to put up walls even before the semester started!

I am not the most vocal student -- my friends know it, my classmates know it, and unfortunately my professors know it enough to call me out on it. This 360 had such a profound impact on my undergraduate learning, but it also brought out the scariest and toughest aspects of the type of learning I would normally shy away from. My goals in the classroom usually include getting in and out without having the professor call on me. This 360 foiled my plans!

One of the many moments in which I, along with several other students, struggled speaking up in was during a fishbowl activity. I can’t quite recall the exact conversation, but I do remember the inner circle of students debating about what it means to be “deserving.” Between a poor law-abiding citizen and an inmate, who did we think deserves an education? The general consensus of the class seemed to agree: Why do we have to choose between the two? Why does there have to be a dichotomy?

I started feeling anxious. I thought, Class is going to end soon, and everyone’s going to leave this class thinking that we completely agree! We will agree that there’s money everywhere, if you look in the right places. Everyone deserves an education, and they are going to receive it somehow! It’s guaranteed! We solved this huge problem!

All of a sudden, I found myself nervously walking towards the empty seat in the middle of the room and sitting down in the inner circle to join the conversation. Once I sat down, I started by asking: Realistically, how is everyone going to receive this education? Why are certain dichotomies allowed to exist in these types of conversations and not others? I explained my skepticism and my issues with their reasoning, albeit clumsily. My classmates saw that, and though they didn’t mean to pounce, they still strongly insisted that there was enough money so that we’d never have to choose one over the other. It came so fast that I couldn’t even respond. I stumbled over my words unprepared, and when I sensed that nobody in this class was going to back me up, I gave up and retreated back to my desk. It was my fault -- Why would I even think of joining this discussion when I clearly wasn’t prepared? Why didn’t I just keep silent like I usually did?

At the end of that class though, I had a classmate (who was usually vocal but hesitated to speak up during this heated discussion) approach me and tell me that she was glad that I even got up to say something, even if it didn’t feel like it made a difference. It turned out that she was struggling with her thoughts -- just like I was -- but was worried about expressing them.

I spent the rest of that afternoon trying to forget that discussion and getting mad at myself all over again for looking like such a fool in class. And then I logged onto our class blog, Serendip, and saw a blog post that a classmate wrote regarding our class discussion:

- I think we need to remind ourselves that we need to shut up and listen to each other. There were a variety of times throughout today I saw people begging for the time to speak, and no one was giving it to them. Sometimes, when we were letting others speak, we were only half-heartedly listening. I don't think we necessarily need more silence in our conversation. Just more awareness: more awareness of how other people are feeling, more awareness of when people need help, and of where we personally are standing in relation to another. One of the main reasons why I love having a debate in a class is that it allows you to see the places that your own way of thinking may have pitfalls. It's hard to find these holes if you aren't allowing yourself to be 1) susceptible to criticism 2) won't allow the other side to speak her behalf. It's great to have a stance, and a strong dedication to that stance, but you are doing yourself a disservice if you don't believe that you may have faults just like everyone else. It is easy and often necessary to simplify a concept and then attack, dismiss, or agree with it, but as our time in our 360 (and hopefully in a liberal arts institution more generally) have shown us, things are not that simple and are indeed nuanced and complicated.

-

"This kind of risk-taking...seems to me to put us as learners...into a place of uncertainty and discomfort. I think this can even be true when the speaker sounds certain." I probably sounded more certain than I actually am, especially after several people challenged my statement. The majority of people I spend time with are of a similar mindset, so I'm not often challenged when I go into a rant about the patriarchy or corporate control or consumerism. And this is one of the things that is so beautiful about our class. I felt comfortable enough to raise these opinions I have to a larger, more diverse group of people, to be accountable for my beliefs even when others might not share them.

- Maybe its just me, but I saw nothing wrong with how our fishbowl went. To be honest, I walked out of class thinking: "Wow! I can't believe we have gotten so close that we can really go there with each other!"....but I guess not? I'm really surprised to hear posts about frustration, lack of silence, apologies, etc. Seeing how this was the most exciting, non-academic conversation we have had, now I am wondering if our normal routine (“You speak, *silence,* Now I speak, *silence*....Okay now let’s refer to page blahblah....”) helps to maintain our walls, instead of breaking them down....sometimes I see a little "impoliteness" or whatever you wanna call it as growth but perhaps that's just me.

So while this particular moment was a tense one for me and the 360 class as a whole, it was also a defining, learning moment. I always made the mistake of not getting up and letting the opportunity to speak pass me by, and my feeling, as a classmate put it: “as though I’m missing out on a code by not asserting my participation in the traditional, verbal way,” but that day I decided to take a big personal risk and think out loud in front of the class. And even though I recognize that “talking is the stock of academic life,” we were, as a class, “working to make vast improvements in our collective ability to pause and listen to each other.”

I still struggle to speak up in class, even after this 360 experience. I think I always will. I won’t become a wonderful public speaker overnight. But as another quiet classmate explained:

- Chandrea, in one of our many conversations on talking in class, has told me that I may not be the student who speaks the most often in class, but that what I do say carries a certain weight – not because it is uncommon that I speak but rather because what I say has a lot of thought behind it. This mirrors how I think about my own participation in terms of the thought and contemplation behind each word. This is where I see myself contributing to my classmates’ learning.

III. Sophia’s stories

As a student, I’ve become used to thinking separately about each of my classes. There are strict boundaries, it seems, between departments and, further, between classes themselves. Within the course cluster Chandrea and I found ourselves in last semester, however, our learning across disciplines was very much supported and encouraged, even to the point that our learning became utterly uncontainable. We were constantly encouraged to make connections among our three shared classes and to make connections outside of those classes as well. One of our classmates, for example, regularly brought in anecdotes and information from the fourth class she was taking – a class called Ecological Imaginings – helping us all to broaden our perspectives on topics such as silence. Without the assumed rules of separation between classes, I found myself constantly making connections back to what I was learning and sharing those connections with others. This is not to say that connections do not happen in other contexts of learning. This is just to say that I needed the explicit invitation to make connections and share them. I needed a context in which the assumption was not disconnect.

There was a consequence to this uncontainable-ness of our thinking, though. Our 360, like an invasive species, threatened to make its way into all parts of our lives. It threatened to overwhelm our social lives, our senses of self and identity, our academic lives and trajectories. For example, I happened to be in the 360 at the same time as I struggled to decide on a major, and the discussions we had in our course cluster led me to change and re-change my mind at least five times in a span of four weeks. In a more social context, a friend of mine who was also in the class had to limit the discussions the two of us had together outside of the classroom to topics that did not involve our 360º. We were overwhelmed by the constant thinking and analysis we did otherwise. We struggled to “turn off” our thoughts – even during the silent practices we did at the start of one of our 360º classes. During dinners together we simultaneously yearned to talk about our readings and classes, and to completely separate ourselves from them for a moment. This kind of learning was all-consuming and exhausting. It was not limited to our classroom walls, it was uncontainable.

One thing that I’ve learned from participating in this course cluster is my own need to contain my learning in some way. Without containers or some form of containment, I feel overwhelmed and am less able to participate in the learning process. If we rely on the environmental metaphor of resource consumption, my mental and emotional resources became too drained by the uncontained learning. What I have begun to take from this is that sustainable learning needs containers/ containment.

In a kind of counter-intuitive way, by building openness into the structure of the 360, my professors enabled me to make my own containers – empowering me to figure out the type and level of containment I needed. Instead of trying to contain our thinking to a pre-determined project or paper, our professors allowed us to further broaden the course’s boundaries by bringing in outside ideas and developing aspects of the course ourselves. For example, a number of students in our class found themselves interested in doing some activism in relation to racially charged events going on on our campus and turned their activism work into final projects for our 360. I personally worked on a more artistic project – a video – as a way of creating my own container to share what I’d learned in the class. The building of our final projects allowed me to figure out how much structure and how much experimentation I needed in order to process the semester and share that processing. And to contain that sharing, we put together a workshop and presentation event.

And the 360 built other spaces for us to contain our thinking. Optional weekly dinners hosted by our student consultant gave me a space outside of class where I knew I could go to continue my thinking about the course topics without infringing on others’ needs to separate themselves. And the very fact that they were optional allowed me to opt-out if I needed some space for my own processing. Serendip, our blog, also gave me an online container for me to think aloud in – as Chandrea mentioned earlier. It also allowed me to express thoughts I would have liked to share in class but needed more time to think through first.

In addition to these spaces of containment, the 360 itself acted as a container or walled community for our learning. The same seventeen students took all three courses. This also meant the same seventeen students did all the readings, went on all the field trips, and had a very shared learning experience. This sharing encouraged us to do more uncontainable and trans-disciplinary learning than we were used to, because we felt empowered by our shared history to reference past discussions and make connections. At the same time – this shared experience is what made it so difficult for us to connect to people outside the wall of our 360. When I would try explaining a discussion I’d had in the 360 to friends who were not in the cluster with us, I found I couldn’t replicate the experience or discussions we’d had and so I couldn’t fully share with them what I was thinking about and what I was struggling with. This container of shared experience is ironically what forced me to rely on new containers to share my experience.

The 360 on the whole was uncontainable – we’re still talking about it, nearly six months later! However, I’ve found containers to be a useful and necessary way of thinking about my learning and compartmentalizing it. Ultimately, the spillover is what makes it a unique experience.

IV. Jody: bringing the audience back in--and "wrapping it up"!

Even as we designed this session, we found ourselves intentionally reaching outside the “container” of academic talks and conference sessions. But also, as it turns out, Sophia’s and Chandrea’s presentations changed between last night when we discussed these and now, so in trying to “wrap up” and open up for conversation, I’m trying to attend to the ways they’ve exceeded the “containers” of their talks, giving us spillover…

Let me say a little bit about our process in putting this presentation together: In the course of thinking ecologically about pedagogy we came increasingly to understand both nature and the classroom in dialectical terms. When Anne and I began planning for this project, we were focused on the uncontainability of classroom life; this was a direction we’d written and presented in before. But as we talked with Chandrea and Sophia, and each of us began to draft, develop, and share our stories of the 360 we all participated in, the tension between containers and uncontainability became increasingly evident. And as this dialectic emerged, it began to seem to us not only to more fully describe what was happening in and spilling out of our linked classrooms but also, once again, to reflect other ecological processes.

Chandrea’s story of the fishbowl as both container and uncontainable quickly took on a metaphoric significance. And Sophia’s characterization (in the midst of our immersion at the ASLE conference!) or the 360 as an “invasive species” that seem to sprout up everywhere and needed some containing made evident the ongoing and inevitable dialectical movement between: containment, eruption, spillover. (? These metaphors together remind me of my efforts when I was in high school to keep a salt water fish tank, wherein unexpected/”other” kinds of matter sprouted and interrupted this intentional ecosystem…) Likewise, we recognize the natural world itself as not only uncontainable but also as constituted by ecosystems with coherent temporary identities and functions, overlapping and nested (like a classroom activity within a class within a 360…), and also vulnerable to disturbance, eruption and transformation.

What does it mean to consider our spaces of teaching and learning – our classrooms and also our multiple other kinds of spaces, including our shared spaces at this conference – as ecological in these (and other) ways? What are the implications for all of our teaching and learning, and for pedagogy about ecology in particular…?

Discussion...of metaphors for the classroom: an "eco-tone," (an "interfingering ecosystem"),

container, guidepost, handle...? and much else: "Natural Philosophy" vs. systems thinking,

"important problems to have," on being put in situations that test your abilities, on trusting students' capacities...

So I’m going to take the last two minutes to “wrap up” – though of course impossible to contain the spillover here!

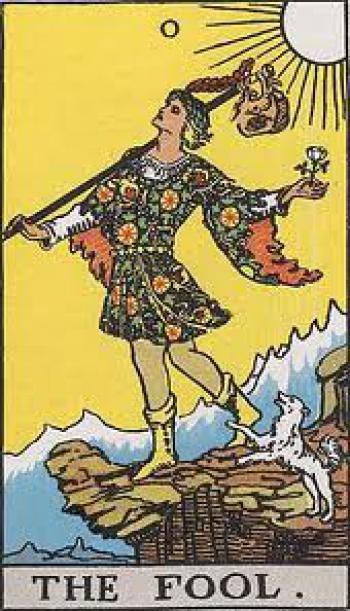

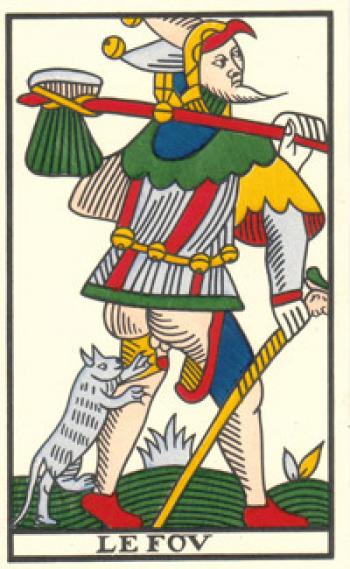

I’m thinking about assessment, again in terms of both world ecological questions and classroom or pedagogy questions. Let’s start by looking at these two images of The Fool – the first in an earlier Tarot deck, the Marseilles, the second in the much later Rider-Waite deck. In the first image a creature stretches its claws toward The Fool’s exposed genitals, but The Fool is instead focused on setting out on his journey; we sense his stride and intent, though can’t see much of his road. In the later version The Fool holds his knapsack over a shoulder and evinces a blithe openness, as he steps over the edge of a cliff… though again, we can’t see enough to know what awaits him.

|

|

Although I don’t mean to cast any of us – learners and teachers – as fools in the lower-case “f” sense of that word, instead I think these images of The Fool remind us of the powerful unpredictability of living and learning, and thus too of assessing what we do and what we learn. I think it’s crucial that we think of assessment over an arc of time in which, for all we may know, there is always much we don’t and can’t know of the world we’re becoming. If we test students in the close-ended mode of federally mandated No Child Left Behind, for example, in which knowledge is understood as highly contained and containable, what of the spillover, the dialectic, the creative, diastolic-systolic learning that may go in directions as yet untried and untested? Likewise, although there are many (often dire) prognoses of our environment, there are also recently told and many untold ways we can see/do/live/learn differently. Rather than telling students “the truth” (or not) about where we are environmentally, can we imagine an assessment in which we recast our ecological pedagogy in terms of what we don’t know, what is yet to be thought, tried, discovered …