Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

The Victories of the Imagination are Enough

The Victories of the Imagination are Enough

In discussing her play, Alice in Bed, Susan Sontag stated that her work embodied the themes of “The reality of the mental prison. The triumphs of the imagination. But the victories of the imagination are not enough.” (Sontag, 117) But one must find themselves asking: that the victories of the imagination are not enough for what, exactly? To find fulfillment in life, to assert one’s own self-identity, to satisfy curiosity, or even to ease “the sense of loneliness and desolation” (James, 87) that Alice James had prefaced her diary with? In correlating the youngest member of the James family with Lewis Carroll’s literary character of the same name, I have found that in these cases, the victories of the imagination, if to achieve some particular form of meaning within both females’ lives, are indeed enough.

Alice James, for most of her adult life, remained an invalid in bed. Diagnosed with what was named ‘hysteria’ at the time, the ensuing treatment for her was to be confined to her bedroom, safely shut away from any stimulation that could possibly upset her. However, it was this very lack of mental stimulation that perhaps caused Alice to retreat within her mind as much as she did, especially as with time she began to associate her body as something she would rather give up for the freedoms offered by the mind. As Boudreau describes, “In detaching her ‘self’—will, perception, intellect—from her body, she rewrites the body as foreign in order to maintain supremacy over her mind.” (Boudreau, 60) So it is through her mind that Alice finds the most satisfying manner to spend her time, allowing her imagination to expand outwards in the meantime.

Another Alice who finds that she better enjoys the realities of her own mind is that from Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland. The book begins with her sitting by her sister outside, who fully well expects her to sit and wait patiently until she should decide that she is finished. Of course it becomes well established that the girl is quite bored, as “Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do…” (Carroll, 5), which is then quickly followed by her discovering and chasing after the white rabbit that should lead her to Wonderland. It can very well be argued that rather than travelling physically to another locale altogether, Alice’s travels through Wonderland were of her own making, having been the product of her imagination while asleep, “…she gave a little scream, half of fright and half of anger, and tried to beat them off, and found herself lying on the bank, with her head in the lap of her sister…” (Carroll, 101) In this respect, much as Alice James resorted to her mind for temporary reprieve from the boredom that so plagued her, so did the other Alice make the same retreat, albeit in a more unconscious manner than her elder counterpart.

The opportunity to use one’s own mind for some semblance of travel, regardless of whether or not such a trip could be considered genuine, presented such a wonderful prospect that it is not surprising how Alice James would have sought to take advantage of it. James (granted, her fictionalized form) makes the pronouncement about the ability of the mind to transport oneself later, declaring that “I can travel with my mind. With my mind I’m in Rome, where Margaret lived. Where Harry descended…My turn now. I walk on the streets. That’s the power of a mind.” (Sontag, 80) She later continues to describe her excursion through Rome, throwing in such descriptions as to make one wonder whether or not she had actually ever visited the city beforehand. She claims to not have, of course, yet the incredible enjoyment she derives from such an occupation simply cannot be ignored, “I do like it, I’m thrilled by it, exalted when I travel there, in my mind. It’s everything I imagine. But then I am only imagining, that’s right. But that’s…the power of a mind. With my mind I can see, I can hold all that in my mind.” (Sontag, 81) The enjoyment James derived from her jaunts about the recesses of her mind is quite evident to see, particularly when considering the extreme limitations visited upon her by means of her body.

For the majority of humankind, the idea of corporal normalcy lies along the lines of achieving a full growth of approximately five to six feet by adulthood, and from there more or less remaining roughly about the same height throughout their lifetime. Of course, the Alice traveling through Wonderland finds herself able to defy this constraint, if only by way of doing so within her mind. Her changing size throughout the book even becomes so commonplace that to return to her regular height is at first almost as peculiar a sensation as constantly adjusting her stature, “…she set to work very carefully, nibbling first at one and then at the other, and growing sometimes taller and sometimes shorter, until she had succeeded in bringing herself down to her usual height. It was so long since she had been anything near the right size, that it felt quite strange at first…‘…How puzzling all these changes are! I’m never sure what I’m going to be…’” (Carroll, 43) Alice James, however, despite her creative ventures throughout her imagination, finds that the opportunity of alternating height to not be so necessary. In fact, the very concept of size is yet another restriction to be considered, regardless of her potential to modify it, “I won’t say how big or how small anything is. My mind doesn’t have a size. One size fits all.” (Sontag, 85) The apparently satisfied tone one would imagine Alice to have spoken these lines with demonstrates a subjective triumph that she would only have been able to find by means of her mentality, wholly separated from her physicality.

In the cases of Alice James and Alice in Wonderland, both find that through travels within their own minds, they may be able to find some sense of fulfillment that they have been looking for. While upon first glance the two ‘Alice’s may appear to have nothing more in common beyond their name, both share their mental escape of boredom as a common ground. The successes they find through them are, at the very least, enough to sustain them through the dull drudgery of their physical lives that they must at some point return to. Therefore, they have both come to find what it is that they truly wished from the beginning. The victories of the imagination were enough.

Works Cited

Boudreau, Kristin. American Literature. 65. Duke University Press, 1993.

Carroll, Lewis. Alice in Wonderland. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Borders Classics, 2008. Print.

James, Alice. Alice James: Her Brothers, Her Journal. Cornwall, New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1934. Print.

Sontag, Susan. Alice in Bed. 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1993. Print.

Comments

On finding a "fit"

Penguins--

I like it very much that you give so much attention to the second of the "ancestors" of Sontag's play: Lewis Carroll's Wonderland. Your comparison foregrounds two significant dimensions of Alice James's life: her being bored, and her giving herself reprieve, in consequence, to live a great deal in her own head, to find there the satisfaction that life "outside" denied her.

But I'm not sure I "get" the central claim of your paper, that the victories of the imagination were enough for both Alices, because both found the fulfillment they looked for. Where is the evidence for that claim? What are the passages you might cite to convince me that Sontag was wrong, in speaking of the inadequacy of the imagination? Just declaring it "enough" won't do; you need to SHOW its sufficiency.

I'd always understood that Alice-in-W's growing and shrinking was Carroll's metaphoric means of showing the experience all of us have, as children, of feeling sometimes too large, sometimes too small, always awkward in our bodies. Surely when Sontag's Alice says, "My mind doesn't have a size" she is speaking directly to her predecessor, suggesting a mental alternative to all such attempts to fit our bodies into established frameworks, freeing ourselves from the need to "fit" a'tall.

Speaking of which: I'd invite you, too, to think about how you might better "fit" your writing to this new venue (medium? genre?) that we call the blog. You might try writing "as yourself" (rather than the "one" who speaks this paper--who's that?). You might explain what, in your own life or interests, motivates your paper, rather than saying that "one must find themselves asking..." Why must "one" ask anything @ all? This is a little ghostly and unanchored....

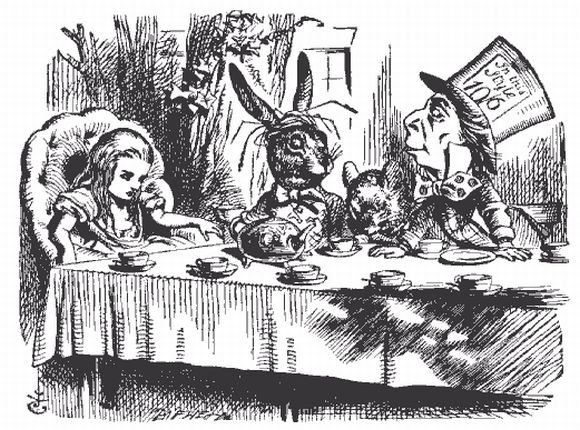

Another nudge might be into other realms of the imagination -- such as the visual -- opened up to your paper-writing repertoire by the resources of the internet. I give you here, as inspiration, both Carroll's tea party, alongside Kundry, who steps out of Parcifal, and Myrtha, who steps out of Giselle, to visit Sontag's. (You'll find another dramatic image of Kundry @ the blog of one of your classmates; see Alice in Layers.) What do you notice in these renditions? Do they highlight any additional aspects of the literary encounter you've staged?