Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Prep Notes for Week 4

repetition:

I've been thinking more about what rachelr said in her post and what we discussed in class about the repetitive nature of Eli Clare's book. ... Last summer, I interned with a judge who worked with both civil and criminal cases. One of the cases I got to sit in on had been brought by a deaf woman. In court, when a questioning attorney asks a question, the witness is supposed to just answer that question, not add anything else. But whenever this woman was asked a question about what had happened, she not only answered the question; she went on at great length about other details until the judge inevitably cut her off. It was strange and somewhat frustrating. I had trouble understanding why she kept over-answering after both attorneys and the judge asked her to stop.

One of her interpreters ... said that among the deaf community, it is common to be overly repetitive or long-worded when telling a story or sharing an opinion. This stems from the feeling of the community (not a universal, stereotyped feeling, but a common feeling nonetheless) that they are not heard. They feel that that they are not listened to and not fully understood. So as a way of forcing others to pay more attention and hopefully gain a better understanding, many deaf people express themselves wordily and repetitively.

I know Eli Clare isn't deaf, and I also know that to put all disabled people in a common box perpetuates the "normal myth" and the idea that all disabled people are the same. However, I think that the deaf metaphor deserves to be extended not just to disabled people, but to all marginalized people. Anyone who has ever felt shunned or kicked to the wayside by society likely fears that they will never be truly heard or understood. This could explain, at least partly, why Clare is so over-persistent in driving his points home.

rhetorical potential of repetition in preaching

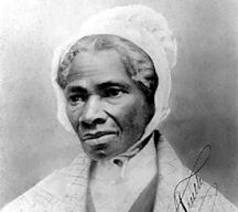

Sojourner Truth

Delivered 1851 at the Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man - when I could get it - and bear the lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman?

Clare repeats the refrain "The body as home" five times over 3 pages (11-13) in Exile and Pride

"The body as home, but only if it is understood that bodies are never singular, but rather haunted, strengthened, underscored by countless other bodies" (11)

"The body as home, but only if it is understood that place and community and culture burrow deep into our bones." (11)

This idea was also put forward by Walt Whitman in Leaves of Grass

There was a child went forth every day,

And the first object he looked upon, that object he became,

And that object became part of him for the day or a certain part of the day,

Or for many years or stretching cycles of years.

Where were you born, where have you lived and how does that burrow into your bones? What does it do to you when people are ignorant or dismissive of your places of origin, growth and development?

My discomfort, feeling of alienation in being a Hoosier on the East Coast

The world as seen from New York's 9th Avenue (New Yorker cartoon)

In grade school, my favorite subject was geography.

draw maps of regions you're most familiar/comfortable with--share

"What I don't say is how homesick I feel for those place names, plant names, bare slopes, not nostalgic, but lonely for a particular kind of familiarity, a loneliness that reaches deep under my skin, infuses my muscles and tendons. How do I explain the distance, the tension, the disjunction between my politics and my loneliness?" (19)for Clare,

memory palaces from Moonwalking with Einstein. The Art and Science of Remembering Everything by Joshua Foer (2011),

p96-105

"The mountain will never be home, and still I have to remember it grips me." (13)

the mountain

I. A METAPHOR

"The mountain as metaphor looms large in the lives of marginalized people, people whose bones get crushed in the grind of capitalism, patriarchy, white supremacy. How many of us have struggled up the mountain, measured ourselves against it, failed up there, lived in its shadow?" (1)

the mountains that feed my soul

The Geography of Childhood: "Both the decision to love and the belief in one's safety in wild country are acts of faith. To commit to either requires the most delicate balance of wariness and boldness of which we are capable." (63)

, find....

"I wanted to belong somewhere." rather than human be-ings, are we better described as human be-longings?

"For Jim and others like him, the woods provide sanctuary, home, and livelihood." (56) Spend 5' and write: What are your places of sanctuary? Can they also be home and places of livelihood?

Why do we need to call our bodies home?

I came across this art exhibition called unmakeablelove (www.unmakeablelove.org) over the summer which I find quite pertinent to our discussions about gender, disability and how society views us. The exhibition is based off Samuel Beckett's "The Lost Ones". The viewer walks into a darkened room and is immediately confronted with images of dark bodies just roaming around this cylinder. There are various flashlights placed outside of the space and the viewer has the opportunity to shine a light onto these moving figures to see what they are. None of the figures have very distinguishable traits - there might be a hint of genitalia on one of them but it is not so obvious.

I made me think about how important our bodies are to us. They are important because society bases so many things about us on just our outward appearance. They are also important because we seem to be defined by how we look like and many a time, we are placed into 'boxes' based on just this outside appearance. Unmakeablelove made me uncomfortable by forcing me to think of the disconnect between my physical body, prone to society's harsh judgements and categorizations, and my internal mind which, while still prone to judgement, is an entity that can no longer be categorized in the ways that we have discussed.

But imagine what it would be like if these bodies of ours no longer existed. If who we are is based on what we are internally. It seems like an abstract idea but if I said that we could create ourselves in a virtual space (as I am doing right now) it is quite tangible. Would we still be characterized? Does my online writing suggest that I am male, female, transgendered, crippled, straight, gay, bi, white, black, hispanic? I'm not quite sure that it does completely. I'm not quite sure that you can put this 'blog post' into a category.

But my question here is really, why do we need to call our bodies 'home'? Clare speaks his reconcilation with his physical body and his mind as though it is so important. While our bodies help us eat, breathe, move, sleep etc. it doesn't do anything else other than put us into the categories that society sets out for us. So why is it so important that we cling to them? Why not just let our mind wander and our thoughts define who we are through simple writing and online communication? Why is it difficult for us to 'live behind a screen'?

http://unmakeablelove.org/movie.htm how do I embed this video from her post?

Quote from video: "We need machines that suffer from the burden of their memory." Jean-Francoise Lyotard (The Inhuman: Reflections on Time, 1991)

Are we more comfortable discussing, imagining burdens than potentials?

We are embodied creatures who crave touch. Infants not held do not thrive. Does this need continue throughout life or do we outgrow it?

Grobstein and Clare Reflections

I was struck by Professor Grobstein's affirmation of Varenne and McDermott's theory that, "cultures provide individuals with a sense of motivation and achievement." This cross-cultural norm, however, has created a disabling effect in cultures "by setting standards of achievement which... [people] can't adequately satisfy."

Professor Grobstein acknowledges this continual practice of cultural disablement and then moves on to suggest what it would be like to create a "non-disabling culture." My first reaction to a non-disabling culture, at least an American culture that actively works to promote enablement and agency was, was that it was an absurd idea. Of course, it's not that I don't think that it would be splendid to live in union and identify with others based on the skills and abilities they do possess, but that I feel we, as humans, are so trained to identify what is different from us.

We spoke last class, when looking at the image of the women in pink dresses, of the voyeur, indentifiying and analyzing difference. I feel this act of voyeruism and practice of being the voyeur is so much a part of the unconscious shared human experience that to promote an abling culture that doesn't point out or identify difference would be near impossible.

Textuality & PragmatismI have a couple of separate threads of thought for this post -- not terribly related but both things I've been mulling over:

1) In this class and in an Anthropology of (Diseased) Bodies course I'm taking, we spend a lot of time with the assumption that bodies mediate our experience of the world, our every interaction affected (and effected) by presumptions made about what our physical selves (queered/gendered, (de)sexualized, (dis)abled, etc) look like and what that look says about our internal selves. However, I want to ask this question: If Eli Clare wrote a book not about queerness and disability, but about some other topic and never mentioned those parts of his identity, would we (as readers) know? Such identities certainly mediate all we think and write, but the form of a book, looking at text produced by a person instead of the bodily person, seems to collapse the starting assumption that it's impossible to interact with the world in any "disembodied" way. Maybe this is an obvious point, and I certainly don't mean to minimize the importance/reality of all those embodied interactions, all that lived experience. But generally, in some way or another, producing and consuming texts is something we can all do, regardless of ability (barring extremes) -- even if it takes a recorded version, a braille version, a special keyboard, someone transcribing, etc. This past summer I read The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, the story of a man who had "locked-in syndrome" and was completely paralyzed and unable to speak, but managed to dictate his memoirs via a system of blinking one eye! I am reminded of the point in Anne's section of the online disability forum that raised questions about the accessibility of graphic novels (to which a student responded with a radio version of Persepolis). Can texts such as Clare's be both liberatory in the sense that they further (in their content) ongoing discussions/theorizing about disability, AND liberatory in that in their form itself they offer one escape from the assumptions inherent to embodiment?

2) In terms of the readings for this week, I think one starting point has to do with clarifying the relationship between the "culture as disability/ability" theory they collectively forward and what a society premised upon such a theory might actually look like. While I find it mind-bending and inspiring to read radical/theoretical texts (and I would put these in that category), I also think it's ok to be annoyed when such theoretical texts never explicitly admit the degree to which their ideas require some kind of HUGE fundamental shift in society. I guess no author is obligated to link their theory to practice, their ideas to actions...but I'm a pragmatic person, and if I'm reading something that assumes we'll be able to overturn capitalism in the near future, I'd like it to at least acknowledge that. I felt like the readings progressively move toward acknowledging the kind of deeper radicalism (especially new political and economic systems) such ideas require. I am curious to see how we put these texts into dialogue with Wilchins and Clare, whose emphasis on linking theory and practice we have collectively admired. How might we push these ideas to better match their emphasis?