Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Thinking About Science: Fact Versus Story Telling and Story Revising

Thinking about Science: Fact versus Story Telling

Notes for a discussion with students in the Bryn Mawr College Science for College program

Paul Grobstein, 24 June 2008

| A loopy story telling perspective | |

|

|

| Science as body of facts established by specialized fact-generating people and process

Science as successive approximations to Truth

|

Science as process of getting it less wrong, potentially usable by and contributed to by everyone

Science as ongoing story telling and story revision: repeated making of observations, interpreting and summarizing observations, making new observations, making new summaries ... individually and collectively Science as skepticism, a style of inquiry that can be used for anything, one which everybody is equipped to to/can get better at/be further empowered by, and contribute to - a way of making sense of what is but even more of exploring what might yet be |

|

| If science is as much about creation as discovery then the "crack"is a feature, not a bug ... and differences among people are an asset to the process rather than a problem or an indication it isn't working |

Trying It Out ...

Which of the following two stories do you prefer?Because of ...

- personal observations?

- observations made by others (personally verified or not)?

- social stories (heard from others)?

- usefulness?

- Very old

- Less old

- Recent

- Still more recent

- SeaWiFS Biosphere Globes

- Ask a Scientist

- Why it matters (sometimes)

- personal observations?

- observations made by others (personally verified or not)?

- social stories (heard from others)?

- other?

- Older

- More recent: Ptolemy, Copernicus (1473-1543), Brahe (1546-1601), Galileo (1564-1642), Kepler (1571-1630)

- Integrating projectiles and orbits

- Recent and when it matters

- Which Way IS It?

Is one or the other story true? Have there been others? Will there be others?

Scientific stories are

frequently efforts to summarize the widest possible range of

observations, always motivate new observations and hence new stories,

should never be understood as "authoritative" or "believed in", do not

compete with or invalidate other stories.

Key issues about scientific stories

|

Which of the following stories do you prefer?

- Existing life forms (including humans) are as they are because of a previous and ongoing process of evolution consisting of random change and natural selection (differential reproductive success).

- Existing life forms (including humans) are as they are because of repeated creative acts of a supernatural being with a plan and intent?

- Existing life forms (including humans) are as they are because of an initial creative act with a supernatural being with a plan and intent?

- Other?

- personal observations?

- observations made by others (personally verified or not)?

- social stories (heard from others)?

- other?

- is one or another story "true"? Have there been others? Will there be? Will this story continue to evolve? (NYTimes Science Times, 26 June 2007)

- National Center for Science Education

- Institute for Creation Research

- Evolution and Intelligent Design: Perspectives and Resources on Serendip

- Science as Story Telling in Action: Evolution (and revolution?)

Loopy story telling science is a tool to help one become better at thinking for oneself

at using observations and stories (of one's own and other peoples') to make stories that motivate new observations that motivate new stories, to create as well as to discoverYour thoughts? ... science as fact or story telling?

Comments

stories, not just for science but for all sorts of learning

Stories in and for Life

How do we learn? Folks say that in each second of life, we receive more than eleven million pieces of information. How do we make sense of that much input? Science teachers tell us that our conscious mind is able to understand and register only about forty out of those eleven million pieces of information, and sometimes not even that much (if we are tired that day, for example). What happens to the ten million plus? They come directly into our unconscious mind. And what that information does in the unconscious part of the mind, we don’t even know – at least not until be become more conscious of what is going on in there.

Are the 10,999,960 pieces of information less important? Science teachers tell us that they are very important – too important to risk holding up the information stream by letting the conscious mind think about it and thereby slow down the process of reacting. The brain scientists tell us that the unconscious part of the brain reacts very quickly, much faster than the thinking part of the brain that we are usually more aware of. A neuroscientist named Antonio Damasio says: “The problem of how to make all this wisdom understandable, transmissible, persuasive, enforceable – in a word, of how to make it stick – was faced and a solution found. Storytelling was the solution – storytelling is something brains do, naturally and implicitly…. [I]t should be no surprise that it pervades the entire fabric of human societies and cultures.” A. Damasio, Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain (New York: Pantheon, 2010) 293.

What all this means is this: We think in story. We are made so that our most important mental processing occurs “in story”. “Story” is the language of experience, and it’s not limited to English, Chinese, or any other animal language. When we understand a story, we understand something about life.

I use this for teaching English as a second language. I can teach students of all ages faster when I use stories. Some of the younger students' parents, however, worry that stories are not a "scientific" way to teach. (This is because I teach in China where "scientific" method is a requirement for teaching.) So words cannot express how happy I am that serious scientists are working on the "facts" of how story words in our lives, in our brains.

When the student learns a story in English, that student’s mind connects the story with the language it was told in, and the student’s memory of the words in that story is combined with the memory of what happened in the story. In this way, the words have a context, and every time they will be used in the future, there will be a memory of the first time the student encountered that word in the story. In this way, each word has a richness to it, taken from the context of the student’s first experience with that word.

Later on, the grammar can be parsed and the grammatical terms learned, but these are explanations only, and cannot convey the real wealth of experience that a word from a story includes as part of its meaning to the student.

This is why the first thing that happens in one of our classes is a story. After the story there follows a short lesson which highlights some of the functions of the English language. The games that sometimes follow all this help the student to digest the day’s class, and eventually workbook practice helps to cement the lesson into place, available for use either in a conversation or (eventually) on an examination.

Back to the scientists – they have studied how we use stories to enable us to better understand and deal with the world around us. Harvard Professor Steven Pinker explains this process in this way: “ Fictional narratives supply us with a mental catalogue of the fatal conundrums we might face someday and the outcomes of strategies we could deploy in them. What are the options if I were to suspect that my uncle killed my father, took his position and married my mother? If my hapless older brother got no respect in the family, are there circumstances that might lead him to betray me? What’s the worst that could happen if….” Pinker, How the Mind Works, (New York: W.W. Norton, 1997/2009) 543.

Children’s stories teach children how to use a story for life, how to create mind pictures that go with and help the student remember the words of the story. The process of learning to make mind pictures is important to creativity and to building the skills for future learning. When a child gets beyond the need for pictures in a book, the creative process of imagining the whole story begins in earnest. Eventually the process sparks the fire of growing understanding of the multitude of stories of life – possibly one of the most important function of education.

This process can begin at any age, but most of us agree that it’s best to start it quite young. This is why even our youngest students start their lessons with a story, and this is also why stories are important to all of our lessons, even for quite advanced or adult students.

Yes, I know childhood development is a science, an art, and, for teaching purposes, an empirical daily test for teachers. I'm suggesting here that the function of "story" seems to be a common thread throughout the process of growing up, in much the same way that the "story" of science, scientific observations and (tentative) conclusions drawn therefrom guides so much of our modern world.

Yes, it's much more than just the simple fact that when the scientific experiment is turned into a story we begin to comprehend and possibly even use it in other aspects of our lives. It's that once anything is made into a story, it comes alive for us brain-driven human beings. And, agreed, we need to learn not to cling to stories that lead us toward anti-social behaviors or the like, and we need to appreciate that stories, like everything else on earth, change. Why even the same story means so many different things each time we read or hear it.

So I'm saying: I love your story; I love the way you're presenting it; I love what that presentation suggests for other disciplines; and I love the boldness with which you're stating your positions on learning and science. Keep it up.

Science is story.

Science is like...being nowhere and everywhere at the same time.

I feel that thinking of science in a way of loopy story or rather a summary of observations that remains until new observations are made that no longer fit the original summary is more useful than the traditional perspective. It allows for one to be more accepting of new and innovative ideas regarding...well, everything. In my experience within Dover's evolution court case I feel that is could have been completely avoided. If the parents and the students were taught that evolution and the ideas of a supernatural beings were not truth but really summaries of observations that have yet to be disproven, people especially parents wouldn't of jumped to the conclusion that the teachers are forcing beliefs onto their children but were really just opening them to new ideas that they can use and accept in whatever way they so choose. To be honest, most of the students didn't mind learning about the different theories but were more bothered by the fact that one simple thing was creating such a ruckus among the small town of Dover. I feel that one huge problem in society is the lack of ability to accept things that seem to be out of the ordinary to us. If we were taught in school how to accept things without necessarily believing in them a lot of controversy would be seen on many topics. I personally feel that at some point in our education the traditional perspective should be dropped and the loopy story telling perspective should be adopted.

Science is story

Science is like stepping into a world where you know how everything around you works.

Looking at science not in the traditional way, but in the loopy story telling way makes science a lot more fun. When using the rigid traditional way, I feel like I have to follow a certain pattern and repeat what I learn in the textbooks. If I don't, I'm going to fail my class. However, looking at science like it is a group of observations that we make summaries from and continue test them, makes me feel like I can be a scientist without years and years of reading textbooks. Finding something wrong in a summary is a good thing, as it is a way to change science and moving it forward. Basically I just feel like the loopy story telling science opens up many more opportunities to learn.

Science's Story

"Science is like a new land waiting to be discovered and explored" -Fabz 2008

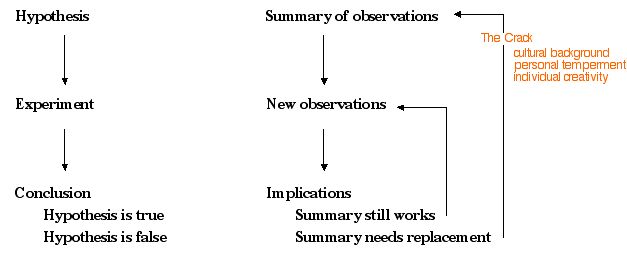

The traditonal persepcetive of teaching science implies that there is a hypothesis that is made, an experiment that is carried out, and a conclusion that is taken from the experiment. The story-telling perspective of science implies that a summary of observations is made, new observations are taken from the summary, and implications on whether the summary continues to work or needs to be replaced is made. The story-telling perspective is more helpful and useful in "conducting" science because it shows how science never really reaches a right or wrong answer, but reaches a state in which the previous summary can be replaced with a new one.

Science is Story

1) Science is like a way of examining the world with a focus of why and how

2) I personally prefer the Science story telling model better than the traditional model for several reasons. The storytelling model allows for more flexibility in the way you look at science. The model also lets more people have different ways of looking at the same observations, which I think allows for a better perspective. When you use the storytelling model to look at issues such as evolution, discussion is easier because none of the summaries listed on the website can be disproven.

Science is storytelling

My first metaphor was: Science is like exploring a new world.

I like the science is storytelling metaphor more. It seems to allow for more revision, more movement and a greater flow of ideas. The summary of observations seems so much more realistic than a hypothesis that needs to be proven true. Proving things wrong seems like a better way of learning science --just like innocent until proven guilty. There is more room for improvement, and more allowances made for bias. It accepts that scientists are human, and uses their bias to create a diversity of ideas (read: summaries of observations) and these ideas can play off each other and create more ideas.

Science as story

Science is like a clock; all the cogs must fit together to function with success, and it functions in cycles (in the respect that one stage must be completed for the next to proceed).

I am a bit indifferent to the way of looking at science presented. While I can see the logic associated with it, I don't believe it is exactly necessary to pick one way of seeing it. I'm sure many successful (however they choose to define "success") scientists have looked at their work in both or either ways.

In addition, many people seek comfort in determining what is seen as the "truth." For them, truth provides stability and support in a sometimes unpredictable world. Similarly, some people rely on religion for this solace.

Science As Story

"Science is like a conquistador...you set sail into a new world, unsure of what you'll discover. Sometimes you have to conquer a few civilizations, but eventually you envelop a whole new world of ideas to understand."

Science as storytelling allows much more room for improvement and growth than the original scientific method. The idea of the constant changing of theories and "summaries of observation" is incredible because no real truth can ever be discovered; there will always be a chance to go back and reformulate ideas and notions that may be different than those of other people.

science is like a story

Science is a toolbox in your brain, knowing and having the tools to approach any problem.

I like the story metaphor because it makes science less "dusty." If science were to be presented in this light, maybe more people could understand exactly how "summaries of observations" work and are usable applications.

Post new comment