Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

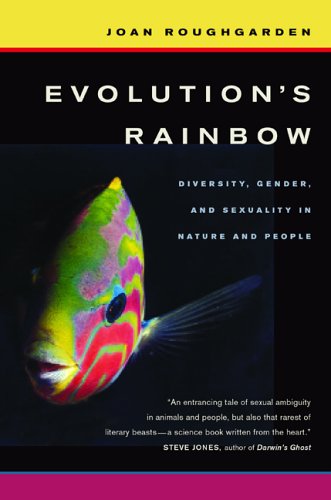

Evolution's Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People

|

Serendip's Bookshelves |

Joan Roughgarden, Evolution's Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People, University of California Press, 2004 Joan Roughgarden, Evolution's Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People, University of California Press, 2004

Commentary by Anne Dalke (August 2006). |

Joan Roughgarden begins Evolution's Rainbow with "the most basic question faced by evolutionary biology": "whether variation within a species is good in its own right or whether it is simply a collection of impurities" (14). The option Roughgarden chooses -- the story of ecology she knows, tells here, and calls other biologists to tell along with her--is the former one, of "endless variation," "always poking through social categories, spilling over the borders, fudging the edges" (396). Insisting that it's high time for biologists to "develop positive narratives about the diversity they're seeing" (101), Roughgarden aims here to correct the "disease model of diversity," the assumption of developmental biology that "one master template is the norm, and that variety reflects a defective deviation"(185).

The guiding images of this story are the complimentary ones of rainbow and ark: a cornucopia of diversity that is both a "genetic asset" and a moral high ground, a primary reason for our learning to know, and respecting, the various ways we are in the world. For the alternative narrative of development shaped by Roughgarden is also one of partnership: it emphasizes the "interrelatedness of gene function and avoids exaggerating the role of genetic control." She replaces Richard Dawkins' "selfish gene" with her own model of how a gene works cooperatively with others, aka "the genial gene" (187):

all the plants and animals above the level of bacteria -- so-called eukaryotic organisms -- are really partnerships at the cellular level . . . . the cell is not a unitary building block . . . . Biologists have been reluctant to think through what this partnership implies . . . . cellular function is not the simple story of a nucleus whose genes imposes its wishes on the cytoplasm. Instead, some subcellular negotiation was required to form our cells to being with, and may still take place. Perhaps the nucleaus and mitochondria have an on-going biochemical discussion, whose breakdown shows up as disease . . . . I feel the discovery of the partnership basis of cells is as important as the discovery of DNA (164). The story Roughgarden develops in such detail, in other words, has a clear, and doubled, punch line: We'd be "better off both scientifically and ethically if we jettisoned Darwin's theory of sexual selection" (164), replacing it with one that is both ecologically more accurate and socially more just. Roughgarden argues that "the DNA story has been relatively easy for people to absorb," because it is simply "a refinement of the narrative of genetic control we've been taught since grade school" (164): "the bowling-a-strike metaphor, the cascade of successive downstream genetic decisions culminating in birth" has been "so persistent in developmental biology, in spite of so much contrary evidence" because of our human "desire to own and control development" (205).If society should embrace this narrative of genetic indeterminacy and interdependency, the implications would be enormous. It would mean acknowledging that "the nucleus doesn't unilaterally 'control' the cells," so "the basic concept of cloning is wrong" (319). It would mean eschewing "biological-based hierarchies" (251) and any "forced bimodality" between two sexes and two genders. It would mean that homosexuality and transgender could come to be understood not as "delterious traits within the framework of Darwinian fitness" (253), but rather as "complex social adaptations" (261). Roughgarden demonstrates, on the one hand, that hermaphroditism is "more common in the world than species who maintain separate sexes in separate bodies," suggesting that it might be viewed "as the original norm" (31). She argues, on the other hand, that the practice of homosexuality is more likely to flourish as a system complexifies: "The more . . . sophisticated a social system is, the more likely it is to have homosexuality intermixed with heterosexuality" (155).

I've recently participated in a number of discussions exploring ideas analogous to those Roughgarden develops here: one was about the social usefulness of our being on a spectrum of abilities and sensitivities; another acknowledged the benefience of mutuations--as "the only way to create diversity of life". And I've just finished reading two intellectual biographies which develop similar lines of thinking: Goldstein's Betraying Spinoza calls into question the notion of an inalterable core identity; Keynes's Darwin, His Daughter, and Human Evolution likewise queries the usefulness of a single position for making sense of human suffering. If my own experience is any guide, Roughgarden's celebration of the rainbow is not as far out as she positions it. She seems to me to have quite a bit of good company in the colorful--and hopeful-- picture she is painting.