December 4, 2015 - 23:06

Books Are My Internet:

Text as Mutable Technology & Reading as Radical Practice

A Saturday morning reflection on the events of the day before, in the prison.

Used books are rarely gifted. When they are, it is typically because their age is indicative of their monetary value—rare first editions of texts or old manuscripts are expensive, and thus the act of gifting them is seen as thoughtful. And on another level: there is life between these pages—from the fingers that have folded a (perhaps unwelcome) dog-ear to the stale scent of the air that seems to never leave the depths of the spine. For many, used books hold a beautiful history. And yet, there was still a deep sense of regret and shame felt among us as we walked into the prison classroom that Friday, offering a stack of used copies of Brothers and Keepers, by John Edgar Wideman. In that moment, handing over a second-hand copy of the book felt like an thoughtless act of charity, an unwelcome performance of power on the part of the facilitators. And still, I left the space with questions unanswered—why, exactly, did this feel so wrong? If what we valued most when we left the prison were the discussions we shared with the women—the collaborative moments that seemed to provide an education for us all—why was I so hung up on how troubled I felt about the physical state of the books we had left?

These questions still hang in the air for me today. And to unpack them demands a deeper look into some questions that may, at first glance, seem fundamental: What exactly is the book? What does it become when we take it into the prison? What qualities does it hold, and what possibilities for higher education in prisons, as a result?

Megan Sweeney, author of Reading is My Window: Books and the Art of Reading in Women’s Prisons, reaches in the direction of these questions in her chapter entitled “Encounters: The Meeting Ground of Books.” As she discovers over the course of her experience leading book groups in a women’s prison, her responsibility as the group facilitator is not so much to select likeable books, but rather, to bring narratives and characters that are complex, and with which the women can engage critically, identifying with them and learning from them. In particular, Sweeney argues that the book group itself was vital in constructing these understandings. Through meeting to discuss plot points, characters, and themes, the women in the book groups “took texts in surprising directions and co-constructed meanings that would not have been possible had we been reading alone” (Sweeney 227). Here, Sweeney illustrates the power of the book group as a contact zone, a space in which various identities and backgrounds come together to address and learn from tensions, and to build off of one another.

Summarizing her findings, Sweeney makes a bold claim:

“As the study progressed, however, I began to realize that the actual books didn’t matter that much. Many women valued our conversations—as I did—regardless of the books’ content. The books served as a kind of connective tissue; they enabled interaction and dialogue, and they fostered women’s engagements with characters, with other readers, with the outside world, and with developing versions of themselves” (228).

Sweeney clearly places the most importance on the discussions themselves—naming the books as mere vehicles to get the participants to these essential points of contact with one another and with themselves. However, an alternative analysis uncover something else. Several of the women name the sense of pride they feel after giving up on a seemingly difficult text, experiencing a breakthrough with the help of the book group, and feeling empowered to read and learn more. One woman Sweeney cites, named Denise, explains:

“…because after doing this book group study, I feel like when I read a book now, not only am I absorbing the story, but I’m really absorbing the characters and I’m really taking a look at where does this woman go? What happens? You know, it gives me a new way to read the book” (242)

Here, it would seem that Sweeney’s claim that “the actual books didn’t matter that much” falls short of the truth—though the experience of the discussion group undoubtedly provided Denise with the self-confidence needed to revisit her book, the empowerment she has gained will now allow her to take the same kind of reflective and analytical skills to her solitary reading practices; her personal education can continue beyond the classroom, with the help of the books themselves and the characters and conflicts they present.

Throughout her chapter, Sweeney highlights a theme of change that occurs on multiple levels—both within the group, within the women, and perhaps even within the books themselves, if on an intangible and invisible level. If the women are able to construct new and various meanings together, this implies that a plethora of meanings may already exist within the book, waiting to be pulled out and named by its readers. This notion of the book as not-so-stagnant and perhaps even ever-changing is supported by a reading of books as a technology—a term commonly reserved for modern inventions such as the internet, communication devices, and social media.

In his piece entitled “A Brief History of the Internet from the 15th to the 18th Century,” legal researcher and technology specialist Lawrence Liang discusses the history of the book. As Liang expresses, though we ascribe an “authority of knowledge” to the book, this perception has not always been the case (Liang 51). On the contrary, he writes of the days marked by numerous errors, forgeries, and pirated manuscripts: “early printing was marked by uncertainty, and the constant refrain for a long time was that you could not rely on the book” (56). This sense of distrust on the part of the consumer is reminiscent of the attitude surrounding the internet today. Common reasoning behind educators’ distrust for Wikipedia as a valid source in academic papers is that because editing powers are in the hands of so many, there is far more possibility for misinformation. Indeed, this fear was the case too in the early days of publishing. As historian Rebecca L. Schoff writes of medieval England:

“Manuscript culture encouraged readers to edit or adapt freely any text they wrote out, or to re-shape the texts they read with annotations that would take the same form as the scribe’s initial work on the manuscript. The assumption that texts are mutable and available for adaptation by anyone is the basis, not only for this quotidian functioning of the average reader, but also for the composition of the great canonical works of the period” (Schoff, qtd. in Liang, 55).

This notion of the adaptable text with a fate and interpretation lying in the hands of its readers is reminiscent of the ideas drawn out by Sweeney. In her chapter, numerous women name a sense that books are “coming to life” for them thanks to comments others have made in their book group—and as a result, they now feel empowered to go read further by themselves and make their own meaning from texts. Though they are not literally editing the books in a way that will affect the reading experiences of other future readers, the incarcerated readers’ effect on themselves and on each other is enough to disrupt the presumed authority of the text. As Liang goes on to explain, the process of engaging with texts in the medieval period “enabled a participatory reading and writing that was simultaneously suspicious of any source of authority”—thus, we should avoid “speaking about authority as something that is intrinsic to either a particular mode of the knowledge production or intrinsic to any technological form” (Liang 58). To apply this analysis to prison reading, it is our engagement with the technology of the book that renders it mutable—if we deem books as possessing an inherent authority and decline the opportunity to challenge this by engaging with them and making our own meaning, we are missing a serious opportunity. Book clubs, as highlighted by Sweeney and as experienced in our own visits to the prison, create the spaces for these opportunities to disrupt presumed authority.

Perhaps this, in itself, is a form of resistance. Perhaps this, alone, is radical. In a space characterized by such intense forms of surveillance, control, and dehumanization, offering a space in which the incarcerated people subjugated by these systems daily are able to reclaim some small form of agency by applying their own readings to a book (and in this way, “adapting” it) is incredibly important. And while we so often question our intentions in the space, constantly wondering if we are reenacting the very hierarchies of power that the women experience every day, we deserve to acknowledge this contribution we make when we carry in texts each week. And here I name a major purpose for book groups as form of higher education in prisons.

Additionally, while the books we bring in may not return to the outside world for a long, long time, Sweeney cites several women who feel that their reading practices offer them a sense of connection outside of the walls of the prison. As she writes:

“Women’s sense of belonging also extended beyond the confines of their discussion groups; indeed, books served as a bridge to the larger community, enabling women to feel like they are part of a conversation that usually goes on without them” (Sweeney 240).

Perhaps, if we think of the physical pages of the book as containing this history, a certain logic would lead us to the conclusion that used books are in fact the very best gift: the wear and tear they bring with them represents the many minds that have shaped and “adapted” the text, dismantling its presumed authority and demanding more meaning-making. And yet, on a fundamental level, this is just not the case—and in respecting the discomfort that we felt upon handing over the used texts, I must disagree with Sweeney's claim that "the actual texts don't matter much." Perhaps best summarized by her later reflection at the end of the chapter: “Our moment of connection continues to remind me of how important it is to let prisoners know that we have not forgotten them” (250). Even if we proudly carry in used texts with the intention of demonstrating years of beautiful, radical textual engagement that have already occurred within the binding, it is simply too likely that this will be read as a lack of care—and this is a risk I am just not willing to take.

Works Cited

Liang, Lawrence. “A Brief History of the Internet from the 15th to the 18th Century.” Critical Point of View: A Wikipedia Reader. Ed. Geert Lovink and Nathaniel Tkacz. Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011. 50-62. INC Reader. Network Cultures, 2011. Web. 4 Dec. 2015.

Sweeney, Megan. “Encounters: The Meeting Ground of Books.” Reading is My Window: Books and the Art of Reading in Women’s Prisons. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina, 2010. 226-51. Print.

Comments

how the actual books matter

Submitted by jccohen on December 5, 2015 - 16:58 Permalink

Smalina,

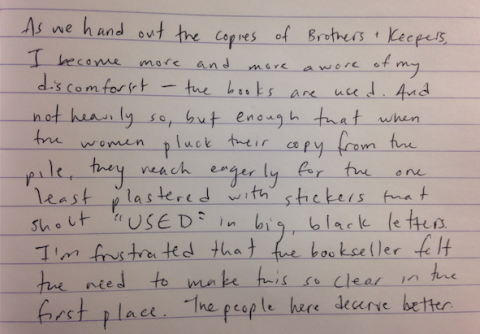

How great that you’ve moved from your own connection to the materiality of books (and their smell!) to this examination of books in Sweeney and in our site. In this light, wonderful to start with a scan of your longhand notes, calling up these several technologies of reading and writing viscerally, as you also move us into your key questions.

You cite and speak back in several ways to Sweeney’s claim that the “actual books” don’t really matter, and interestingly, the question of whether and how they might matter – a question that might itself be said to matter intellectually and emotionally as well as physically – circles through and around a number of ‘readings’ of books and of reading. Ultimately, as you return to the used books we carried into the jail that day, I’m convinced that all aspects of texts including the physical are fluid, and that gifting itself is about this circulation.

In this regard, I appreciate your point that “change…occurs on multiple levels—perhaps even within the books themselves,” which relates to reader response theory and the notion that texts are incomplete without us/readers; interesting to hear this in the historical context and in relation to current debate/uneasiness about the internet. While you note that Sweeney’s “responsibility as the group facilitator is not so much to select likeable books, but rather, to bring narratives and characters that are complex, and with which the women can engage critically,” it seems that the fluidity of texts may mean that “complexity” and “critical engagement” lies in the meeting of reader and text rather than in the text itself. And what a compelling notion: that “this [bringing in of books and inviting our own readings], in itself, is a form of resistance”!

(By the way, in a chapter we didn’t get to, Sweeney also goes more deeply into the materiality of books – worth a look, I’d say.)