Horse is only one letter different from house. A horse is ours and hours where a house is only yours or belonging to you all. It is not only the size, but the material requirements that make horses so expensive; they need to live in a complex ecosystem to thrive. Meanwhile, the ecological nightmare is this disturbed and disappearing mare impossible to touch by means of technology. Wick gives us the limitations of technology to disturb but not hold life. Horse will serve as a mirror for humanity and more if and only if humanity is listening to the history of the archive and the virtual, because it is important to attend to even as technology evolves.

Horse is only one letter different from house. A horse is ours and hours where a house is only yours or belonging to you all. It is not only the size, but the material requirements that make horses so expensive; they need to live in a complex ecosystem to thrive. Meanwhile, the ecological nightmare is this disturbed and disappearing mare impossible to touch by means of technology. Wick gives us the limitations of technology to disturb but not hold life. Horse will serve as a mirror for humanity and more if and only if humanity is listening to the history of the archive and the virtual, because it is important to attend to even as technology evolves.

In her second collection, Horse, published with Broken Sleep Books, Rushika Wick has given the reader a microscopic and telescopic picture of what home means. She explores the forms home can take for humans from earth to space station to archive of what is lasting. It is a feeling for the environment that endures even when the archive becomes a geological record adding layer after layer after inserting sentiment pun here. The Takhi, or Przewalski’s horse epitomizes this mixture of sediment and sentiment as the last wild breed of horses in the world. These horses were houses for Mongolian nomads.

In her second collection, Horse, published with Broken Sleep Books, Rushika Wick has given the reader a microscopic and telescopic picture of what home means. She explores the forms home can take for humans from earth to space station to archive of what is lasting. It is a feeling for the environment that endures even when the archive becomes a geological record adding layer after layer after inserting sentiment pun here. The Takhi, or Przewalski’s horse epitomizes this mixture of sediment and sentiment as the last wild breed of horses in the world. These horses were houses for Mongolian nomads.

Serendip is publishing this engagement with Horse to continue its open ended inquiry into climate change, literature and technology. The horse and human interaction anticipates the human archive interaction the flying away, the loss of layers. It attends to the ways in which the later interacts with the earlier. Wick writes:

An Earth archival project

She was there, at the edge of the field, looking into the distance. For a moment, she turned her oblong head, elegant neck straining, equilibrium disturbed by my proximity. Before I could reach my hand out to her, fist full of grass, she was nothing but a memory - silt carried loose in the river. -Archivist

The river is alive to what is found and what is washed away. The archive is likewise what is found and what is washed away by the river revealed in the silt on the riverbank and river bottom and giving the river its own anatomy. In this way the epigraph becomes the genome becomes the summary that will unfold and unroll through the different laters of Horse.

Horse is a metaphor of course of course what Wick does is deploy this knowledge as a layer within the work. She brings into focus the history of the human equine relationship. She gives us horses’ loss of environment and relationship with their environment, this species wide trauma, as a way to understand coming impact of climate change on humanity. Horse asks us to consider what it means to be a human outside a traditionally human environment? Wick gives the reader a new metaphor for trauma, the Mongolian horse reintroduced to the world outside the time and environment that made it. The genome of horses and humans is an archive that preserves and the very problems it reveals by means of incomplete information.

Wick makes the interplay between animal and intellectual makes the archive an embodied problem. It blurs the distinction between the archivist and researcher in the sensory realm, making the researcher read what is written into domestic knowledge. Her exploration of the body of the problem recalls Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space. Bachelard writes:

“Something closed must retain our memories, while leaving them their original value as images. Memories of the outside world will never have the same tonality as those of home and, by recalling those memories, we add to our store of dreams; we are never real historians, but always near poets, and our emotion is perhaps nothing but an expression of a poetry that was lost.”

Horse is suggesting that despite all that will be lost in the future, a feeling formed in the body of the organism might not be. The interplay between animal and intellectual makes the archive an embodied problem. It blurs the distinction between the archivist and researcher in the sensory realm, making the researcher read what is written into bodily knowledge.

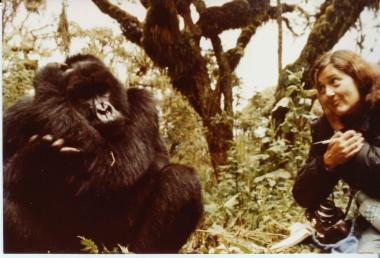

Dian Fossey is an absent present in Horse, her statue and her writings are present, and yet like everything else inside the archive, she is absent. She pioneered active conservation, a kind of direct intervention to address poaching in protected areas, during her time studying the Mountain Gorillas in Rwanda. There is a two-fold departure from our reality outside the archive.

Dian Fossey is an absent present in Horse, her statue and her writings are present, and yet like everything else inside the archive, she is absent. She pioneered active conservation, a kind of direct intervention to address poaching in protected areas, during her time studying the Mountain Gorillas in Rwanda. There is a two-fold departure from our reality outside the archive.  Wick writes: “Dian appears to have undergone a number of positional transitions, at some point actively disappearing her age and gender within her writings.” First that Fossey lived until 2021 and second that her life was celebrated. For fans of her work in primatology this is a delightful fantasy. Then the speculative fiction begins to speculate how the world would be different if a woman dedicated to protecting an endangered species and by extension its environment had not been murdered. It is beautiful inversion of the classic science fiction question: what if Hitler had been killed. Here is the archive in practice adding a layer to what is already present. Dian serves also serves as a foil for the archivist herself and sets out a speculative geology telling the reader where to find our priorities for a good life.

Wick writes: “Dian appears to have undergone a number of positional transitions, at some point actively disappearing her age and gender within her writings.” First that Fossey lived until 2021 and second that her life was celebrated. For fans of her work in primatology this is a delightful fantasy. Then the speculative fiction begins to speculate how the world would be different if a woman dedicated to protecting an endangered species and by extension its environment had not been murdered. It is beautiful inversion of the classic science fiction question: what if Hitler had been killed. Here is the archive in practice adding a layer to what is already present. Dian serves also serves as a foil for the archivist herself and sets out a speculative geology telling the reader where to find our priorities for a good life.

The archivist is another reader as the reader is another archivist and the reader of the archivist is another reader otherwise said you are here. In a very literal sense every horse is an archive for the lived experience is recorded and stored inside their brain. It is training. It is also the role of evolution. For a human to have a sustained and training relationship with a horse is to turn into an archivist. It is a feeling for the animal and psychology. The archivist is reviewing and strengthening some memories that serve the animal well in the sense of letting them adapt to their environment. It is creating a home from memory. The archive is only a history of horses and riders all the way down. The rider needs to find themselves at home on the horse and the horse needs to find themselves at home with the rider and they must come together as rooms in the same home. It is precisely this finding and writing that Wick describes so utterly meticulously in the work of her archivist character. In this future, dystopian or not is for the reader as the rider to decide. The archivist is writing into the archive.

A horse is a story of hope of course, the Mongolian horse turned loose in the Chernobyl exclusion zone in an environment radically polluted by humanity, where humans fear to live is living. It is foreshadowing the not too distant future in which some humans are living in an exclusion zone like planet earth and others are living on space stations. The book asks the reader what they are hoping for the future. For me, Horse is an open ended inquiry into the nature of domestication and what we come to define as a good home.

A horse is a story of hope of course, the Mongolian horse turned loose in the Chernobyl exclusion zone in an environment radically polluted by humanity, where humans fear to live is living. It is foreshadowing the not too distant future in which some humans are living in an exclusion zone like planet earth and others are living on space stations. The book asks the reader what they are hoping for the future. For me, Horse is an open ended inquiry into the nature of domestication and what we come to define as a good home.

Works Cited:

Bachelard, Gaston. Poetics of Space. trans. Maria Jolas, Beacon, 1 January 1994.

“Dian Fossey Biography.” Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund, 2024, https://gorillafund.org/who-we-are/dian-fossey/dian-fossey-bio/. Accessed 1 August 2024.

Lida, Gretchen. "CEOLCHUAIRT MONGOLIA: A IRISH FIDDLER’S JOURNEY.” Books and Film, Horse Network 12/19/2019 https://horsenetwork.com/2019/12/ceolchuairt-mongolia-a-irish-fiddlers-journey/. Accessed 30 July 2024.

Wick, Rushika. Horse. Llandysul, Wales, Broken Sleep Books, 2024.