Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

“Y’know what they call a unicorn without a horn? A friggin’ horse.” - Disability, Sexuality, and Passing in Glee

With an average seasonal viewership of between nine and ten million, the television show Glee holds a prominent place in the American prime-time lineup. Having recently resumed its weekly broadcast on the Fox network, the television show, now in its third season, centers around the trials and tribulations of the New Directions, a glee club at the fictional McKinley High School. Composed of social outcasts of varying race, gender, sexual orientation, and disability, the group prides itself on allowing anyone who auditions to join; however, their theme of acceptance is not reflected by the school and the club, as such, faces numerous setbacks.

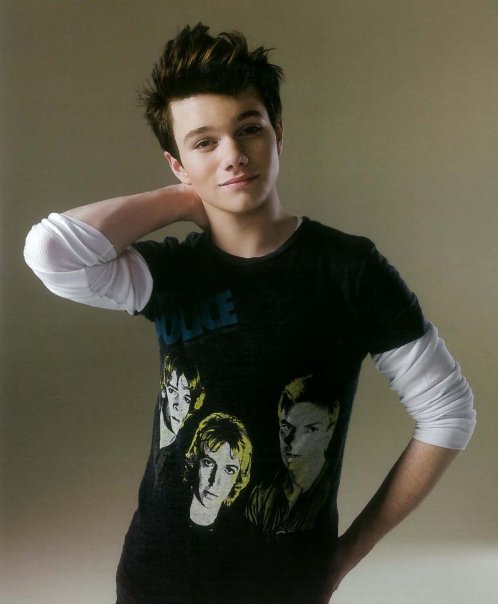

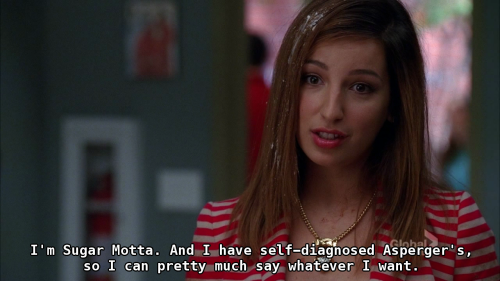

One of the recurring themes on Glee is that of gender/sexuality and disability. Of particular note are two characters: one is Kurt Hummel, a male student who identifies as gay, is regularly bullied and, though still facing personal doubts, has become more self-assured with the progression of the last two seasons. The other character is the newly introduced Sugar Motta, a female student who claims to have self-diagnosed Asperger’s Disorder, which she believes gives her the equivalence of diplomatic immunity and allows her to say anything she wishes. Within this paper, I’d like to specifically focus upon these two characters as they are portrayed in Season Three, Episode Two; a recap of this installment may be found here.

Kurt, an aspiring actor who feels the need to pass as straight in order to achieve traditionally masculine stage roles, struggles with self-expression of sexual identity. In this episode, he has chosen to run for class president and has agreed to have another classmate, Brittany Pierce, serve as his campaign manager. Brittany, a simpleminded cheerleader, wants to flaunt Kurt’s uniqueness by comparing him to a unicorn as a campaign strategy. When Kurt approaches her about wanting to tone things down and stresses his desire in not wanting “to be known as ‘Kurt Hummel, homo,’” Brittany responds with a straightforward question: “What’s wrong with that?”

Later, in a conversation with his father, Burt, Kurt describes the type of Broadway role to which he is a shoe-in (ex: La Cage Aux Folles, Falsettos, Miss Saigon) versus that which he would like to play (ex: the male-lead in West Side Story):

Burt- “What is wrong with any of that? It’s who you are.”

Kurt - “And I’m not saying that I’m ashamed of it. The problem is that if I want to be an actor, I have to pass as straight to get the great romantic roles. And I want those roles. Every actor does. But to not get a shot at it? I mean, it kills me.”

Yes, the profession of acting is all about passing as something you are not, and Kurt is smart to realize this. However, the issue at hand has more to do with self-pride than anything else. “Pride is not an inessential thing,” writes Eli Clare in his book Exile & Pride: Disability, Queerness and Liberation (Clare 107). “Pride works in direct opposition to internalized oppression. The latter provides fertile ground for shame, denial, self-hatred, and fear. The former encourages anger, strength, and joy” (109). Kurt is able to reach beyond the internalized need to present as more masculine within the plot line’s forty-minute limit; however, one would be wise to assume that this theme will be recurring throughout the current and future seasons.

In addition to the show’s portrayal with passing in terms of sexuality, the second episode also features passing as regard to disability. However, the aforementioned character of Sugar isn’t passing as able – she’s attempting to pass as disabled. In the season premiere, Sugar immediately introduces herself as having “self-diagnosed Asperger’s, so I can pretty much say whatever I want…I’m pretty much like a diplomat’s daughter.” Let that sink in for a minute…

Firstly, Asperger’s has specific criteria in regard to diagnosis and isn’t something that one can just diagnose themselves with. Secondly, it appears, through reading online postings from viewers, that the main issue with the portrayal of an individual with self-diagnosed Asperger’s is ignorance. With each delivery of Sugar’s dialogue, I feel as though I’m being slapped across the face because this girl simply does not know what she’s talking about. If she really had a diagnosis or was correct in her own assumptions, she would know that people who have Asperger’s cannot turn on or off what they say. Many also do not have the capability of such blatant sarcasm, which Sugar uses when she tells her vocal coach that she “worked that song like a hooker pole” or when she specifically says “NOT ASPERGER’S!” after verbally abusing Will Schuester, the teacher who leads the New Directions, as he informs her that she cannot join the club.

Writer Julia Bascom recently dedicated an entire blog entry to the subject, entitled “Sugar, Self-Diagnosis, Appropriation, And Ableism: So Here’s What You Missed On Glee.” She writes:

“…the utter and complete and raw awfulness of Sugar doesn’t come from her being a bitchy and entitled rich girl who can’t sing and isn’t used to getting her way. It comes from her strutting into a safe space these kids have created and pretending–and not even pretending very well–to be something she’s not, something she can turn on and off at will, for fun and profit, at no cost to herself and every cost to them.”

Sugar’s presumed ignorance makes me wonder: what is she using a self-diagnosis of Asperger’s to hide? Is she really just a loud-mouthed teenager who feels that she can say whatever she’d like? If this is the case, then it does not make sense that she would need to defend her stance through the cloak of disability.

The Internet has proved to be an prime medium for instant discussion and feedback on pop culture; disability and gender on Glee are the topic of several heated discussions on Facebook and Twitter, as well as official and unofficial online forums. Using the Web as a level playing field, viewers of all abilities are able to weigh-in and voice their opinions, express displeasure, and discuss matters prevalent to the television show and their personal lives with others who identify similarly.

People are literally talking about such matters: a recent episode of the online radio show, “Raising ASD Kids and Teens” featured Sharon DaVanport, Executive Director of the Autism Women’s Network and Beth Arky, a writer for the Child Mind Institute covering Asperger’s and Autism in a discussion on the introduction of Sugar and Asperger’s in the season premiere and second episode. DaVanport, who has Autism and identifies as a “Gleek” (the name for highly-devoted fans), cites the show as leading the way toward diversity and personally applauds them. She said in the interview that she has “an oddball sense of humor” and is “trying to be patient” with the direction the show will be taking with Sugar, but at the same time has been “a little bit horrified.” Arky said that the character of Sugar is featured in three episodes and that the question remains as to whether she will become a recurring character (Arky feels that she will). Arky, also a fan of the show, went on to say that the majority of the population would not pick up on the “self-diagnosed” component of Sugar’s claim to disability, something that the ASD community would latch onto right away. This “reinforces stereotypes that people with Asperger’s are rude and that they do say whatever they want, and that there is no filter for other people.”

Glee is both a community to the characters portrayed within its plot line and the viewers who tune in each week to track new developments. I’ve really latched onto Eli Clare’s idea of “the body as home,” which is a theory that both Kurt and Sugar are evidently missing. Especially relevant is Clare’s proposal that the body is home “only if it is understood that bodies are never singular, but rather haunted, strengthened, underscored by countless other bodies” is especially applicable to this particular episode of the small screen drama (Clare 11). Kurt is directly affected by the actions of his peers within his pursuit to take on a more masculine homosexual identity: Brittany pushes him to represent himself with a more flamboyant, feminine image, while he is laughed at by both his peers and teachers for attempting to come across as more male through an audition.

Interestingly, the individuals who jest during his audition all face discrimination for disability or personal image: Shannon Beiste coaches the varsity football team and was taunted with false rumors of being a MTF transsexual; Artie Abrams is a wheelchair-bound teenage male who desires ability; Emma Pillsbury is the high school guidance counselor who has mysophobia and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Glee is a cultural phenomenon, a culture in and of itself. However, like any culture, it comes with its own set of problems. How does one, or rather – a team of writers – incorporate disability/gender/sexuality into a television show without stepping on any toes? The fact of the matter is that it simply cannot be done. Someone somewhere will always be offended by something, to keep things in the most general of senses. The acceptance policy of the New Directions, that they will take anyone who tries out for the club, is one such example. “In every society, there are ways of being locked out,” write McDermott and Varenne in their paper “Culture As Disability.” “Race, gender, or beauty can serve as the dividing point as easily as being sighted or blind. In every society, it takes many people—both disablers and their disabled—to get that job done” (McDermott, Varenne 3).

While I remain dissatisfied with way in which two characters have been recently portrayed, the show does one thing very well: it builds upon characters’ abilities rather than disabilities and attempts to create a space where physical, mental, or emotional limitations are not crippling. “By building on strengths rather than trying to correct deficiencies, we might actually lead more satisfying an productive individual lives,” writes Paul Grobstein in his February 2010 Serendip post “Cultures of ability.” “And maybe, by learning to be less critical and more generous with ourselves we could as well contribute to bringing into being a more humane culture, a culture of ability rather than disability?”

Comments

pride and passing

Although I among the 99% of Occupy Philadelphia, I am in the tiny minority who has never seen an episode of Glee (although after reading your web event, I do plan to tune in or catch an earlier season on Netflix.)

The Serendip web event format works beautifully for your argument and you embed images of the characters and incorporate links to advocacy websites and radio shows to good advantage. (However, as a naïve reader, I found the video of ClevverTV's overview of the episode to be too detailed and not particular helpful.)

On a basic level, the question of whether (or when) it is appropriate to use one’s difference to gain political advantage—as a potential campaign strategy for Kurt and as a way to gain “diplomatic immunity” for Sugar—permeates this episode. However, you dig deeper using the theoretical framework advanced by Eli Clare to interrogate how pride and internalized oppressions intra-act in the motivations and behaviors of Kurt and Brittany. I’m left to wonder though how pride and internalized oppression play out in the character of Sugar.

Perhaps keeping your argument focused on the complexities of passing would provide a more unifying theme for examining how gender, sex and disability are entangled in this particular cultural representation. You highlight that, “Yes, the profession of acting is all about passing as something you are not,” and explore how this plays out for Kurt, a gay teen actor seeking traditional leading male (more masculine) roles and rejecting a unicorn theme in campaigning for class president. Is his primary goal to be accepted—as an actor who can convincingly portray “masculine” and as a candidate who is "more than just gay" within the broader school community? In both cases, the fear of being type-cast seems to be a key motivator.

In your argument, Sugar represents a different dimension of passing, one that you and other advocates critique. For those who know more about Asperger’s and Autism Spectrum Disorder, her character does not “pass” but rather reinforces cultural stereotypes about ASD. I’d be interested to know how Sugar’s character develops in subsequent episodes and whether her misrepresentations provide an opportunity for the audience to learn more about ASD.

You've introduced several important ideas here, and there's clearly much more to say about the entanglements of passing. Perhaps you'll want to continue to explore this topic in your final project?