Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

An Exercise in Reading Gertrude Stein, or...

An Exercise in Reading Gertrude Stein

or

PRACTICAL PUDENDUM

How does Gertrude Stein, in her limitless capacity to confound the reader, imbue her texts with the philosophies of William James?

Although this essay centers on a tiny excerpt from “Objects” from Tender Buttons, I believe that an attentive reader can extrapolate characteristics of William James that resonate throughout the entirety of Tender Buttons.

William James, in “Philosophical Conceptions,” explains, “Philosophers are after all like poets. They are pathfinders. What every one can feel, what every one can know in the bone and marrow of him, they sometimes can find words for and express” (346). Through his philosophies, James attempts to provide new context for abstract words such as belief, truth, and faith. Although his essays labor to create a more flexible background for these terms, the linguistic baggage is unavoidable. On a smaller scale, Gertrude Stein’s writing takes everyday words, sets them in new situations, and ascribes shifting meanings. Stein does not tackle large, grandiose terms, but prefers to force the reader to question everyday language.

Stein also highlights James’s emphasis on individualism. “Objects” does not lead the reader to a predetermined conclusion; rather, the text opens doors that would have remained closed had the text formed grammatically correct and coherent sentences. As James states in the conclusion to “The Varieties of Religious Experience”:

You now see why I have been so bent on rehabilitating the element of feeling… Individuality is founded in feeling; and the recesses of feeling, the darker, blinder strata of character, are the only places in the world in which we catch real fact in the making… Compared with this world of living individualized feelings, the world of generalized objects which the intellect contemplates is without solidarity or life (770).

James insists that no idea or object has an end, there is always another layer of relationships waiting to be discovered.

Stein urges the reader to go with one’s gut instinct, one’s feelings as a response to her mishmash of words. If she were aiming for logic, she would have used more punctuation than the rare comma and constant period.

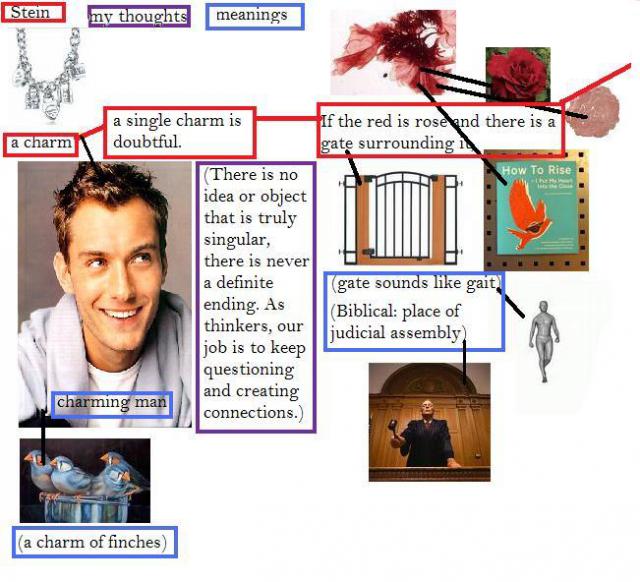

Engaging directly with Stein’s texts, here are a few methods of reading “NOTHING ELEGANT”: individual words vs. an overarching theme

NOTHING ELEGANT.

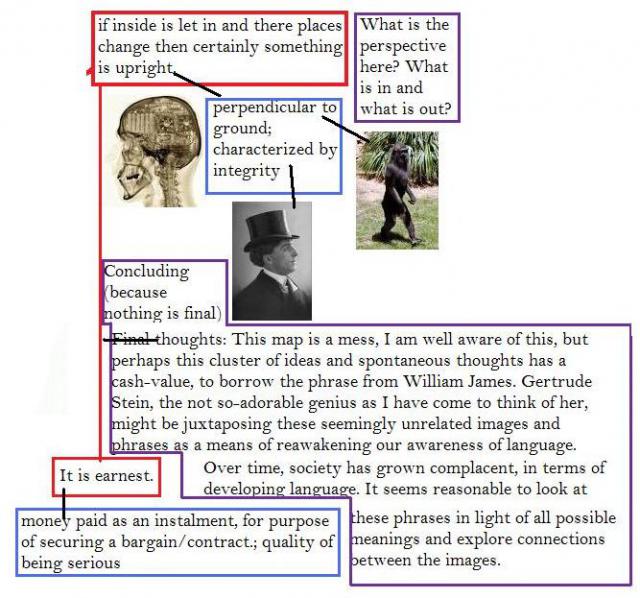

A charm a single charm is doubtful. If the red is rose and there is a gate surrounding it, if inside is let in and there places change then certainly something is upright. It is earnest.

(If you would like to look at those images in one screen, I have attached the original document. I couldn't make the image size-large enough to read comfortably if the image was in one piece.)

Normal 0 false false false EN-US X-NONE X-NONE

NOTHING ELEGANT.

A charm a single charm is doubtful. If the red is rose and there is a gate surrounding it, if inside is let in and there places change then certainly something is upright. It is earnest.

Yeah, Gertie, I hear you. You string words together like so many mismatched beads, but you know exactly what you are doing, don’t you? Why don’t you share with the class?

After reading this section a few times, I thought about sex, or rather the female genitalia. When glossing this passage in class I said something about Beauty and the Beast, but my time spent apart from the text has given me another idea. If Stein can write, “a wife has a cow” from "As a Wife Has a Cow: A Love Story" and mean an orgasm, who is to say she cannot write about a rose and mean a vagina? Because you know, Stein would just love it: a college class dancing around the possibility that she is describing a vagina.

Stein connects words with double meanings in order to create a buffer zone, a level of ambiguity in which exploratory connections can form. We cannot settle with a surface image of a rose and a gate, maybe a forest in the background, because underneath that image a new neural pathway begins to form.

In the beginning, we have a charm a single charm. Let us call that virginity. The notion of virginity is a tricky thing, it is doubtful. Most people are not going to call you on it, and if they do, well… a slap works nicely. If you have ever seen a production of “The Vagina Monologues,” you know that there is usually a part devoted to the uniqueness of shape and color of every vagina. Perhaps Stein is invoking the impossibility of exactness with the uncertainty of “if.”

The bit that really made my head hurt was the image of “if the inside is let in, and there places change”. We could be literal and assume that if the hymen is broken, then an inner layer is broken and reveals another layer of interiority. There is a change, both physical and mental. The larger implication of this phrase is that an internal change occurs as a response to another internal catalyst. If we confront our sense of self, our identity, surely we respond accordingly.

Continuing the metaphor of virginity, a broken hymen means the term “virginity” no longer applicable and one’s internal description changes as a result. No longer would you refer to yourself, even in the privacy of your mind, as “So-and-so the virgin.” Perhaps you could now be “So-and-so the sexually active.”

Normal 0 false false false EN-US X-NONE X-NONE

I am going to skip over the obvious response to something is upright in this metaphor, and muse about the implicit meaning of this short sentence. I hope that Gertrude Stein had more in mind than a vagina when she penned this particular sentence, and I think that the bigger picture develops by acknowledging the relation to the rest of the prose. How does this section relate to the larger grouping of “Objects”?

Well, the title of this particular section of Tender Buttons is “Objects,” which could mean that Stein regards virginity as an object to be discarded, or perhaps revered, but either way there is a certain amount of materialism ascribed to virginity. If this is so, then is it possible that Stein is trying to even the mental playing field between men and women by removing the stigma of virginity? Virginity implies purity, innocence, a lack of experience, none of which is conducive to producing gripping literary pieces. We do not want to hear how you finished a sewing pattern; we want to hear how you stabbed that fellow, the one who got fresh with you, with a needle (just for example).

Through the lens of the smaller section title, “NOTHING ELEGANT,” we understand that whatever charm, whether it is virginity or not, that Stein is referencing, is not and should not be, placed on a pedestal. Her subject does not require special attention or consideration.

Gertrude Stein helps ground William James in literature by drawing from his belief that "the full truth about anything involves more than that thing" ("Hegel" 513). Stein's texts invoke meanings resulting from the words themselves, not merely from contextual clues. "Objects," and in particular "NOTHING ELEGANT," exposes the forgotten corners of language with the bright light of confusion.

Works Cited

James, William. "Hegel and His Methods." The Writings of William Jame: A Comprehensive Edition. Ed. John McDermott.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1977. 512-529. Print.

"Philosophical Conceptions and Practical Results." 354-362. Print.

"Conclusions [to "The Varieties of Religious Experience"]." 758-782. Print.

Stein, Gertrude. Tender Buttons. New York: New York: Claire Marie, 1914; Bartleby.com, 1999. 19 April 2010. Web.

Comments

A rose is a rose is a rose (or not!)

A rose is a rose is a rose (often interpreted as meaning "things

are what they are," a statement of the law of identity...)

fabelhaft--

I LOVE it that you resurrected that passage from “Philosophical Conceptions” where James explains that "philosophers are like poets," pathfinders who can find words to express "what every one can feel, what every one can know in the bone and marrow." Doing that w/ Stein's poetry, rather than with James's philosophy, makes the ideas embedded in the philosophical language more easily accessible to those of us w/ more concrete, poetically associative sorts of brains.

Certainly one thing that you've highlighted here, in your complimentary use of words and images, is the way in which Stein's playing w/ language exemplifies James's nudging us to avoid reiterating old habits, to escape some closed systems (of method, of interpretation, of thought), to search for a way to enact conversations that might be more interactive, and therefore inevitably more unpredictable, in their outcomes. I'm especially fond of (and grateful for) your attempt to create an image of the way a stream of consciousness might run, in its multiple branchings.

I'm also amused by your attempt to provide a single coherent reading of the "Nothing Elegant" section as an exploration of female sexuality. You might be intrigued to know more about the very complimentary work that has been done by feminist critics with Stein's poem "Lifting Belly," read as erotic precisely because it refuses to be "explicit," because it is veiled or coded. As the infamous critic Judith Butler asks, in her essay on "Imitation and Gender Insubordination,"

"Can sexuality even remain sexuality once it submits to a criterion of transparency and disclosure, or does it perhaps cease to be sexuality precisely when the semblance of full explicitness is achieved?....I would like to have it permanently unclear what precisely that sign [the word lesbian] signifies....[to establish] the instability of the very category that it constitutes."

So now I'm noting that my own notes to you, beginning with "the law of identity," have ended in its explicit refusal: the permanent "unclearness" of any sign. In which direction will your own musings branch next?