Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

The Show Begins

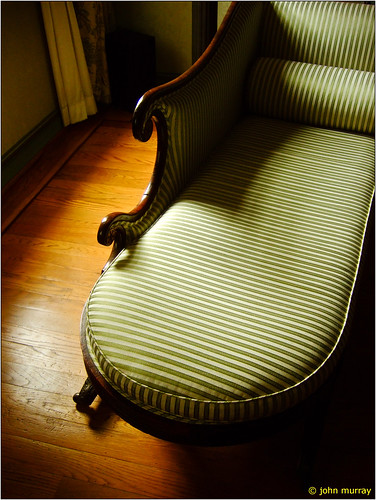

I walk into the theatre, all her family, friends and those who call themselves her friends, sitting in the burgundy velveteen rows of seats that ripple out from the stage. In the centre of the stage, one light shines down, dim and yellow with age, on a chez lounge.

She limps out coughing, sputtering, clenching her stomach as if she fears some demon is about to emerge from her navel. She looks at the audience, knowing they could not hope to understand her art, directs a few piteous looks at the front row, and takes to her bed with a sentiment of familiarity and comfort that spreads like warm honey through the auditorium. The act of lying down becomes some sort of enticing dance of broken parts: some stray paper contorting its way across a blustery day. She lays her arms delicately beside her frail body as her neck gives way to gravity and her head kisses the pillow in exhalation.

The show begins.

Riva Lehrer asks people to stare at her, and other’s, disability. She performs the art of disability so that the awkward side-glances that happen when you walk past a physically disabled person on the street are not necessary. The paintings in her collection titled “Circle Stories” show these bodies plainly: how her legs and feet “don’t match up” with her head and shoulders, how Tekki Lomnicki uses crutches to manoeuvre around, how Susan Nussbaum is “confined” to a wheel chair. The truly valuable piece of her art, however, is her ability to make you see past what is staring at you and inviting you to stare back.

The first few seconds spent looking at a Lehrer painting involve figuring out what part of this person’s body makes it different than the viewer’s? Then one begins to see all that is taking place outside of the body.

In the case of Susan Nussbaum, the foreground is of her looking boldly at the viewer. Earlier I used the word “confined” to relate Nussbaum to her chair, but this painting completely contradicts that common wording. The world is flying around Nussbaum, a compact, a pencil, a steering wheel on fire, but she looks bravely forward in a tranquil awareness few people possess.

The painting of Mike Ervin and Anna Stonum has a man (Ervin) and a woman (Stonum) in wheel chairs in the foreground. This is the first second of the painting. Behind them, flashes of lighting dominate a bright blue sky full of white clouds. The next second. Next, the viewer’s eye is drawn to Mike’s hand on Anna’s knee and her smaller hand cupped on top of his. This tiny visual incident of relationship and connection takes the viewer away from seeing Ervin and Stonum as “disabled persons” and moves him/her closer to seeing something way more complex about Mike and Anna as people who are undeniably in wheelchairs, but Lehrer makes that shallow observation irrelevant to the bigger depiction of the relationship.

Lehrer asks people to stare at the subjects of her paintings, knowing that they will find more. She makes a spectacle of disability, hoping the spectator will see the show differently through her lens.

The nurse was wrong from the beginning of Sontag’s play, “Alice in Bed”. For Alice was a performer: in taking to her bed, she created a silent ruckus that not even a Bull in a china shop could hope to equal. She was a double performer, and her own audience throughout her diary. In performance of disability, Alice also satirized her gender. She couldn’t “live up to” Henry and William’s example, though she had the mental capacity to do as much, if not more than they did during their lifetime. As a woman, Alice would have been seen as an inferior being; “unable” and “weak”.

By taking to her bed, by performing her disability, Alice James has asked us, her audience to stare, the same way Lehrer asks us to. Stare long enough at her frailty as a hysteric, her exhaustion, her stomach pains, and one can see the satire Alice James wrote under the surface of her diary. She develops an irony that stays with a reader throughout her diary. The agency that is found in her ability to speak about others in a demeaning way and her refusal of patronizing visitors is juxtaposed with the longing, helpless condition we know she was physically overcome by. By seeing this pitiable weakness of body next to this force of mind and will power, one is forced, by the frustrating inequity of parts, to see past Alice’s foreground performance of disability and to look into the underlying performance of gender. Alice’s true disability in life was not being a hysteric, it was not her stomach pains and ultimately it was not even her breast cancer. Alice James was disabled by the gender constructed for her by the society she was born into. She was held in bed by a force far greater than bodily exhaustion. Alice was held down by her ability to see the confinements few others could. She performed her disability as a satrization of her genderized handicap for her contemporaries, but few could see. In writing her diary, Alice James, delivered her performance to an audience that could better appreciate and see the multiple layers of the inaction.

Comments

"Enticing dance of broken parts"

kj--

Very dramatic: your title, your images...like many of your classmates, you are working hard on the possibilities that the internet provides for imaginative play. Don't forget, in the process, some of the critical conventions, such as the need for citations (wherefrom, for example, those striking images? Where is "Circle Stories" available, and in what format?)

Equally dramatic is the way you open: it's so vivid to begin w/ the empty, lit stage, with an audience of those who "call themselves friends" (a creepy foreshadowing? One that you don't follow up on?). And your description of the actress Alice's act of lying down as "some sort of enticing dance of broken parts: some stray paper contorting its way across a blustery day" is sheer poetry.

Be sure to look @ aseidman's project, and @ fabelhaft's: both are also "plays."

Your use of contemporary crip art to "read" Alice back to us is also quite effective, but/and also hampered by the lack of context and citation. It's hard to follow your analysis of the paintings of Susan Nussbaum, Mike Ervin and Anna Stonum, for example, without our actually being able to see what you are describing. I'm confused, too, by exactly what claims you are making about the effect of Lehrer's work: on the one hand, you say that it makes "awkward side glances...not necessary"; on the other, that the work is

inviting you to stare back." Do you mean that her art instructs us to REPLACE awkward side glances w/ direct stares? Or teaching us not to attend to the overtly visible--the wheelchairs--but rather to the "bigger relationship" of the people in those chairs?

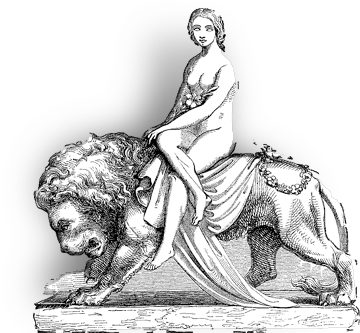

All this functions quite effectively as instruction for how we might behave in the bedroom of/in the presence of/while reading the diary of Alice James, who "asks us to stare." Your movement from talking about Lehrer's work to James's diary is a little fitful: as in your analyzing paintings we can't see, you analyze text we can't read: you say that "the nurse was wrong"--but what did she say? But then you move quite effectively into your second big point: that Alice asks us to stare not only--not even primarily--@ her illness, but rather @ her performance of the disability that is gender: "By seeing this pitiable weakness of body next to this force of mind and will power, one is forced, by the frustrating inequity of parts, to see past Alice’s foreground performance of disability and to look into the underlying performance of gender." Especially effective is that awful picture of the bound foot w/ which you end, as an image of the constrictions of gender. I can't bear to look; I can't stop looking. Shudder.

Time Stamp Fail

Okay so it is definitely 5:01 right now but the time stamp on my essay says 5:56pm.

SERENDIP FAIL