Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Mental Health and the Brain: Working Group, April 13

Mental Health and the Brain Working Group:

Thoughts welcomed in the on-line forum below.

Summary

Ryan introduced Alzheimer’s Disease as the first topic of the evening. Alzheimer’s is commonly viewed from a biomedical perspective as opposed to a mental health perspective. His concern was that due to either the culture of science/medicine or the nature of the disease, compared to other diseases or mental illnesses, we have little knowledge about what Alzheimer’s looks like “from the inside”.

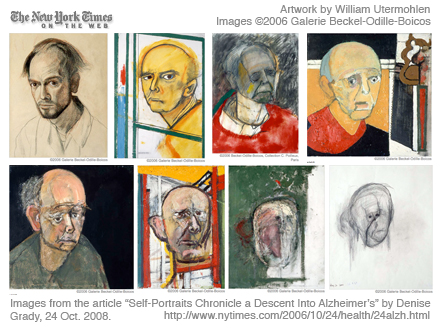

An exhibit from the NY Times was offered as a look into Alzheimer'ss. The art work is of an the American artist William Utermohlen and spans chronologically from before he acquired Alzheimer’s to his paintings done in the midst of the disease.

The above lead to a discussion about “storytelling” in general and memory in particular. What is memory? And is Alzheimer’s the loss of the material correlates of individual memories? If the latter is true, this would mean that Alzheimer’s patients cannot remember things because they’ve lost the memories. But a different understanding of memory leads to different conclusions: Memories are not “retrieved”, but rather created anew by the conscious (storyteller) every time such memories are experienced (much like dreams?). As Oliver Sacks puts it, "…Bartlett describes in Remembering: that remembering is an active (hence 'creative') process of reconstructing and revising, and not a passive reproduction of a fixed 'memory trace.'" A new/better way to think of Alzheimer’s may be that the biological correlates of memory (whatever they are, and wherever they are represented in the unconscious) are not lost, rather the ability to create a cohesive “story” from among “pieces” in the unconscious is impaired. It is not that the loss of memory is contributing to the symptoms of Alzheimers, but that a person cannot remember because he/she cannot tell stories. Alzheimer’s is a lack of the ability to confabulate.

A fascinating phenomenon involving memory is that of patients with Alzheimer's or other forms of dementia. It has been observed that Alzheimer's patients or others with some form of dementia will show emotional responses on the anniversary of a loved ones death, even if they cannot consciously tell you anything about that person or his/her death. Thus, there is good evidence for a "declarative" form or memory (associated with the hippocampus; being able to recount factual events) and "emotional memory" (the amygdala). Interestingly, these patients have been reported to respond positively to greif work in therapy.

The personal stories below were discussed (from the Alzheimer’s Association website):

I started drinking and doing drugs at 11. I was severely addicted and took over 100 pills a day along with the drinking.

In my late 40s, I started noticing some forgetfulness – like everyone my age – but it continued to get worse, and other things started to happen. I had done so well in my job, but then the forgetfulness turned to confusion, time loss and not recognizing people I had known for years. I started to have tremors and huge bouts of anger from nowhere.

I see people I don’t recognize. My speech is terrible, which makes me self-conscious.

Ted

The first manifestation of something being amiss with my memory was in late 2004 when I began to have problems remembering some details relative to my job.

Having noted this memory issue, I compensated by taking copious notes about problems and writing detailed procedures for system operation, as well as problem diagnosis and correction. This helped the memory issue, but slowed me down as I could not always remember steps that were easy for me to remember in earlier times, which required me to stop and look up information in my “cheat sheets.”

I have few new memories to speak of as recent events just do not stay in my mind on a consistent basis. As a result, I feel that I am robbed of any future because while I will live in it, I will be unlikely to remember it.

My wife is now my memory, and I can write this only with her ability to remember parts of my life that I am getting fuzzy about.

Richard

Sometimes, when I am at my best, they try to persuade me my doctors don't know what they are talking about. When I then explain my symptom, then they act as though I am helpless and should be institutionalized immediately, as if there is no middle ground. They don't realize how insidious this disease is, especially in the early stages.

While I am still able, I want to articulate and give voice to what it is like to walk in these shoes and let people know that given this diagnosis, we are capable of contributing to the world around us. Please listen to our voices – individually and collectively.

Pete

I tried to relax, not to think about what might be happening to me; but it was there, like the sound of distant thunder, lurking on the horizon. I knew something was wrong, had sensed it for sometime, and it was beginning to scare me.

I have more and more instances where I just cannot visualize spatial geography, can’t see in my head the layout of streets, sense directions, or remember what particular intersections look like.

Kris

I started to become forgetful – which was not like me at all. I had an almost photographic memory and relied on that all my life. I had a very stressful job and worked long hours, so I blamed that for my forgetfulness. I couldn’t remember things like my home phone number, my associates’ names or on bad days, how to get home.

I tried desperately to hide it and became pretty good at it!

My husband likened it to the Titanic – that the ship was sinking, and he and my son were going to survive and I wasn’t. My son reflected that it was like his mother was on death row, but innocent of the crime.

I’m definitely not the same person I once was. I’m not as outgoing, not as self-sufficient, not as engaging and definitely not the life of the party!

Sandy

I am now in my world, a world of confusion, fatigue, and most days, in severe pain.

I used to be this very independent, overachiever. And now, I am this very dependent underachiever, which causes me much frustration. Where things used to be very easy for me, all things now I find very complicated – even the easiest task.

A participant offered as an example a personal experience with Alzheimer’s. When visiting her father with a friend, her friend went to the father and said that she was his daughter. The father accepted that she was a daughter. Where do unconscious intuitions stand? The man may have not been able to say for sure that the friend was his daughter but it seemed he would have been unable to tell a story why the friend was not his daughter. Maybe this suggests that Alzheimer’s patients should be encouraged more to rely on instincts and intuitions, even if they can’t consciously justify or rationalize such feelings.

The Mental Health and the Brain course (Fall 2008) arrived at “the ability to explore” as a possible definition for being mentally healthy. But do Alzheimer’s patients lose the ability to explore? Another suggestion was that in order to maximize a patient's ability to “explore” and create meaning, someone else in that person’s life could assume the role of whatever function it is that the patient is losing. More concretely, a support person would help the patient to identify people, find missing things, orient them, remind them of past experience they've had, etc. so that they can go on doing the things that they CAN do (see the case of Richard above).

--- summarized by Laura

Katie used our conversation about Alzheimer’s Disease as a starting point for discussing identity and the self. The storyteller is responsible for defining the self by creating personal stories. Memories are important components of these stories. There are infinitely many self-defining stories possible. The competition and/or adjudication between these selves is part of the process of developing an identity.

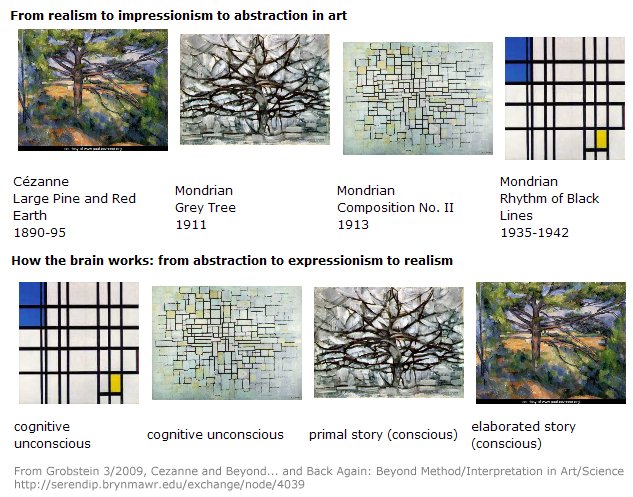

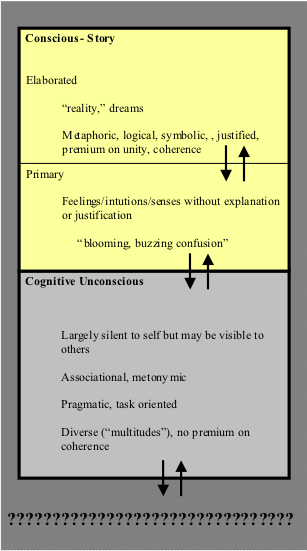

The relationship between the self and the brain was discussed in terms of bipartite and tripartite models of the brain (see image below). The bipartite brain model consists of the cognitive unconscious and the storyteller. The cognitive unconscious receives input from outside the nervous system. It is task oriented, associational, diverse, and minimally available to the self. The storyteller has two smaller components; the primary story and the elaborated story. The primary story is mostly intuitions and feelings, or to quote William James, a “blooming buzzing confusion.” This chaos is made sense of by the logical, metaphorical, symbolic, and coherent elaborated story. The bipartite system can be mapped onto the tripartite system developed by Damasio. Both models allow for the existence of multiple selves.

Damasio’s proto-self is analogous to the cognitive unconscious; it monitors and represents the physical state of the organism. Changes in the proto-self are in turn observed and characterized by the core self, which is similar to the primary story. The primary story is examined and made sense of by the autobiographical self. It is interesting to note how these three components of the self interact. The proto-self is capable of influencing the core self and being influenced by the autobiographical self. The core self responds to the proto-self and affects the autobiographical self. The autobiographical self is altered by the core self and changes the proto-self. The interactions between the selves that Damasio allows differ from those of the bipartite brain. In the bipartite brain there are reciprocal exchanges between the cognitive unconscious and the storyteller.

The discussion also turned to meditation. Meditation was discussed as transcending James's "blooming buzzing confusion". Is meditation "turning off" the storyteller/elaborated self? Or is it separating that self from the rest of the brain (primay self and/or the unconscious)?

Lastly, the model above was applied to Alzheimer's. Is Alzheimer's the loss of the "elaborated story" ("realism") as above, with only the "primary story" ("impressionism") remaining intact?

-- summarized by Julia

Comments

I am liking the idea of

I am liking the idea of either a "pre-conscious" or "primary story", and am wondering where emotion best fits. Whereas feeling an emotion is necessarily conscious, it seems more immediate, intuitive, and influenced by unknown things in the unconscious; thus, it wouldn't seem to qualify as an "elaborated story".

I too was thinking about the concept of multiple selves. During the discussion we placed on the board various (sometimes mutually exclusive) boxes in the unconscious, which were represented as different selves. However, I think it also makes sense to think of multiple selves involving the conscious as well. Similar to a "generalized control mechanism" where there are widespread changes within both the conscious and unconscious. So, a particular story would go with a particular box in the unconscious. And just as a box in the unconscious might prompt a certain story in the conscious, so too might a certain story in the conscious necessitate a certain box in the unconscious.

I was very interested in

I was very interested in the concept of the "self" that we touched upon with Katie's presentation, and when discussing Alzheimer's.

The first thought that came to mind, before our detailed discussion was, "I act different around different people because I know their emotions, their values, the situation… and I wonder, when am I actually “myself” if “myself” means uninfluenced by others? How does one differentiate between the selves? Why are the selves distinct, and not just impulses of one self?"

While my question wasn't entirely answered, I did receive some particularly interesting insight on the topic. Something I took out of the discussion was that my own perception of me was actually a very elaborate self-deception. Many of our actions/behaviors are produced by the unconscious part of our brain (the second level in the bi-partheid brain model). It seems that the self is actually an overlapping 'entity,' for lack of a better word, that both depends on the unconscious and the conscious levels of our brain. The self, to me, seems like a culmination of information made into a relationship--as we dubbed, a storyteller. There is no real 'entity,' but rather a flow of information that is processed according to our own individual means, thus providing a differing sense of "self" from person to person.

Finding selves by deconstructing self

Rich conversation, with valuable intersections to discussions going on in other venues. As documented in Laura's summary above, it may well be useful to think of Alzheimer's (and other dementias?) as a progressive loss of story telling ability starting with more "elaborated stories" and extending "downward" toward primary stories. Such a loss is consistent not only with imagery but also with many of the "inside" reports, including "can't see in my head the layout of streets," "my world, a world of confusion," "I could not always remember steps that were easy for me to remember in earlier times," and "memory"" problems generally. Indeed it may well be that loss of memory, the most obvious feature of dementias, is actually secondary to a more general loss of story telling ability (creating patterns out of the somewhat incoherent signals reaching the story teller from the unconscious). There is progressively neither past nor future but only the present ("I feel that I am robbed of any future because while I will live in it, I will be unlikely to remember it").

What also struck me from this conversation is some similarities in from the inside reports to other "mental health conditions," building on our earlier discussion. There is clear evidence of a split self here ("I tried to relax ... but it was there, like the sound of distant thunder, lurking on the horizon"), as in depression, schizophrenia, and other "disorders," and of distress caused not only by that but by concern about the reactions of others to one's condition ("we are capable of contributing to the world around us . Please listen to your voices ..."). People are clearly being distressed by internal evidence of their own incoherence, but that discomfort is being made worse by concerns about interpersonal reactions and inadequacies.

Could the distress be alleviated by a greater recognition/acceptance of incoherence as to some degree characteristic of all brains, and as a source of potential rather than a failing? We presume the incoherence of infancy to be generative. Could we do the same with that of dementias? At least so long as there continues to be an internal recognition of incoherence there is still some story telling capability that, as in children and as in other "mental health" conditions, could be encouraged, for the benefit of the sufferer as well as the rest of us? Might this offer a more productive approach to dealing with dementia than regarding it as loss of abilities?

The discussion of Alzheimer's linked nicely to a review of Damasio's writing about the neurobiology of self and I found it very useful to be reminded of Damasio's concepts of "proto-self," "core self," and "autobiograpical self." And that, in turn connected to some recent development of my own ideas about the "bipartite brain." Damasio's "proto-self" is clearly part of the "cognitive unconscious," while his "core self" and "autobiographical self" are experienced and therefore part of the conscious/story teller. The "core self," though, is less elaborated than the "autobiographical" self, corresponding perhaps to the distinction I draw between "primary" and "elaborated" stories. I orignally made that distinction to acknowledge the difference between experiencing something in the world and accounting for it/making sense of it, but it would seem to work equally well for distinguishing between different senses of "self."

All this connects in intriguing ways to Alzheimer's and both conceptual and therapeutic approaches to mental health issues generally. The primary "story" can be thought of as very much like what William James described as a "blooming, buzzing confusion." Perhaps what is at issue not only in Alzheimers but a wide variety of mental health situations is a reduced ability to influence the "stream of consciousness," to find/create elaborated stories that either distract one from it or actually smooth it out? Does elaborated story directly impact on primary story, or must it do so indirectly by acting on the cognitive unconscious? What about meditative practices, Csikszentmihaly's "flow state"? Could these provide exemplars that might be of use in thinking about therapeutic practices for dementias? for other mental health problems?

Post new comment