Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Mental Health and the Brain: Working Group, June 29th

Mental Health and the Brain Working Group:

Thoughts welcomed in the on-line forum below.

Summary

The military recently decided not to award the Purple Heart to soldiers suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a result of their service. Historically, the Purple Heart has only been award to those suffering non-treatable, "physical injuries". The issue is very contentious; some people argue that the medal should be reserved for "bloody and undeniable" and "concrete and uncomplicated" circumstances. Others are disappointed that PTSD is not recognized because as many as 1/3 of soldiers experience symptoms. Is there a distinction between physical injuries and PTSD that’s worth preserving? Or should the distinction be done away with, and the Purple Heart be awarded for PTSD?

One source of concern may be that the military is distinguishing between physical and mental injuries. Post-mortem brain analyses of soldiers has shown considerable brain damage, which looks a lot like brain injuries linked to cognitive decline, stress, and depression in football players. From this it follows that these "mental states"—stress, depression, etc.—can be explained by physical damage in the brain. Why make a distinction between losing a limb and injury to the brain? Still, not everyone understands or attributes significance to brain research.

A discussion about the nature of physical injury arose, and one participant posed the question, Does a physical injury have a "storyteller" component?—that is, is the conscious mind directly affected by, say, a broken leg? Perhaps not as much as a "mental injury/disorder". A physician treating a broken leg would not need to inquire into the relationship between the conscious and unconscious, as a psychotherapist might. But, is the distinction really that one injury is superior (physical injury) to another inferior one (PTSD, brain injury)? One participant added that she would be inclined to create a new medal for PTSD and brain injury, and possible even consider these injuries nobler than physical injuries.

Another participant suggested that maybe the military is just trying to avoid the complexities of defining and thus acknowledging PTSD and brain injury. Someone suggested that the concept of "blame" might be significant. Most people might consider that a soldier who has lost his leg is not to blame—enemy fire is responsible. Who would you blame for a soldier developing PTSD? Is the condition due to a personality flaw or weakness? The military trains soldiers to put mind over matter: to walk and run longer, to survive with less nourishment, to act quickly, and so on; basically, to survive under extreme circumstances. Does PTSD not fit into this perspective? After you’ve trained a soldier, it may be hard to acknowledge something "invisible" from the outside that can’t be measured, some "imperfection" that might incline someone to develop PTSD. Service men are thought of as perfectible, and so maybe the logic is that a medal cannot be awarded for something attributed to an internal failing or the non-perfectibility of a human being. Acknowledging the imperfectability of individuals would put the entire enterprise of the military into doubt. The military wants to award above-human behavior.

The discussion turned to the broader possibility that the military is a simple reflection of culture. Do we as a culture want to reward some behavior and not others? Do we want people to act in predictable ways? Do people want/need incentives for things? If every injury in the military were awarded there would be less of an incentive to put oneself in harm’s way. Furthermore, the military wants soldiers to act in predictable ways—to take risks for the greater good. Rewarding certain behaviors and not others is a way of socializing people, both in the military and in a broader, cultural sense. Can we escape the tendency to socialize people? Maybe if we want to change the military, we first need to change the culture. How do we change the culture? By first changing ourselves. But would individuals be willing to do this? Everyday we act in ways that reward some behaviors and discourage others. One discussant offered an example: If someone walking down the street passes someone in shabby clothing, who is talking to himself, and looks like he hasn’t cut his hair or nails in months, most people who not engage him in conversation; thus, society is discouraging this type of "behavior". Maybe we want and need people to be predictable. Would you rather have someone be less predictable when they’re driving? Would you rather political leaders be less predictable? And so on. Maybe then, one can’t disapprove of the military because individuals act in essentially the same way everyday.

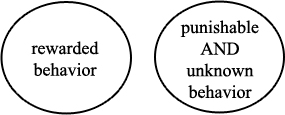

In summary, the discussion arrived at the possibility that the question of who deserves a Purple Heart is not based on a distinction between the mental and the physical. This argument is a stand-in for the general inclination to socialize people and award certain behaviors and not others. Culture is faced with three types of behavior: "good" behavior that is rewarded; "bad" behavior that is punishable; and "unknown" behavior that is not understood. These are then separated into two categories, rewarded behavior and punishable behavior; the unknown defaults into punishable:

Comments

mental stress training military program

NYT Aug 18 2009, Mental Stress Training Is Planned for U.S. Soliders

This military training program is aimed at "heading off", among other things, PTSD. Yet, if there's evidence that in some, if not many, cases PTSD is a manifestation of closed head brain injury, you can't "head off" PTSD... yes, someone can be "trained" to manage it, but the idea that you can prevent it with mental stress training is silly.

While I like the ideas of Beck and Ellis that it can be useful to examine one's thoughts and emotions, that doesn't mean that one should deny them. I think the program gets that wrong by attempting to give soliders "intensive training in emotional resiliency".

Still, even if "mental toughness [could] be taught in the classroom", would we want to conceptualize it as "toughness"? I don't think so.

the mental, the physical, and social validation

I went into this conversation about the Purple Heart/PTSD/closed skull brain injury controversies with the feeling that it was a classic case of the need to achieve more general recognition that all behavioral changes are changes in the brain and needed to be dealt with simiilarly. I still think that's so, but acquired an entirely new and somewhat unsettling perspective on the Purple Heart controversy. Thanks all.

The issue of physical versus mental damage is actually irrelevant to the Purple Heart policy. What is relevant is socialization: the practice of encouraging people to behave in particular ways by giving symbols of social validation to people who the social group can say as unambiguously as possible display the behaviors one wants to encourage. The problem with PTSD and closed skull brain injury is that many people are unsure whether one can distinguish between people actually "injured" and people who are instead either "faking it" or displaying an undesireable lack of self-discipline/will. Presumably this will change as people become more familiar with the evidence of brain changes associated with trauma.

What's more unsettling though is the need to recognize that in important senses we all do what the military does in awarding Purple Hearts. We all "validate" behaviors in others that we can readily identify as "positive" (by whatever standards we happen to use) and, without intending it, we also fail to validate not only behaviors we don't approve of but those we have trouble evaluating. People in grey zones tend to get lumped in with those we know we don't want to validate. How to avoid that particular sin is an important and interesting challenge that I need to think more about.

Just another quick

Just another quick thought... I was just talking with someone in the military and mentioned tonight's discussion. His opinion was that purple hearts should go to only injuries, physical or otherwise, that are untreatable. It is his belief that PTSD is treatable and therefore shouldn't merit a purple heart.

That thought is of course relevant only to the specific case which we started out with... don't know if it is relevant in the larger, abstract picture that emerged.

I think it's incredibly

I think it's incredibly interesting that, if we consider the Army as a separate culture just as the United States has a culture, the change in regard toward mental health in the United States should therefore begin to correspond in the Army way of life. The Army prides itself on honoring the utmost United States "values" -- and when those values begin to change, like the consideration of mental health in society, as should the Army's own consideration of mental health. We see from many points of view, as highlighted in the New York Times article arguing for purple hearts for PTSD, that the view of mental health is changing -- and therefore, this supports the above philosophy: that if the Army upholds the values of the USA, should it not honor the changes of those values in society?

On another note, incentives were brought up in the discussion. Therefore, should the Army really BE encouraging the USA's "values" by giving incentives that almost perseverate the "goodness" of being injured? Should the Army put that much focus on "values" that are constantly changing and hold different amount of significance to different people? If we are to put this kind of emphasis on incentive, like the purple heart, people will always be striving to receive them -- it is our culture's disposition. It, to me, is almost like encouraging injury in war as honorable.

.....

Post new comment