Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Week 7: Disability, Sex, & Gender

This week we turn to an exploration of disability and the field of disability studies. For Tuesday's class, please read Lennard Davis's "Constructing Normalcy" and as much of Nancy Mairs's Waist-high in the World as you can. Thursday we will continue our discussion of Mairs and begin talking about Rosemarie Garland-Thomson's "Seeing the Disabled." What new ideas and perspectives did you glean from the reading? What did you find surprising or perplexing? How might we put disability studies and sex/gender studies in conversation with one another? How might we incorporate questions about disability into our discussion of the issues and texts you've chosen for the remainder of the course? How do we construct stories--orally, textually, visually, musically, or in other forms--about disability?

Pregnant and Paraplegic...

I remember watching this when I was younger and think it's an interesting extension of our conversations on disability. Enjoy!

health.discovery.com/videos/baby-week-paralyzed-pregnant-part-2.html

Dr. Seuss on IEPs

During last week's discussion on disability studies I got particularly interested in the notion of "the invisible disability." As a result, I started thinking about learning disabilities and the particular role that a learning disability has played in my own life. Even though I have come very close to overcoming my learning disability there are still times when I find myself reminiscing about my childhood years and the struggles that I faced as a "disabled child." From elementary school till about the end of middle school I was very secretive and uncomfortable with the fact that the educational system had identified me as being "different" from my peers.

Going back to last week when I started reflecting on my own history with a disability I started thinking about all those individuals (both family members and educators) that supported me during a time when I saw myself as being intellectually inferior to my classmates. Of all my supporters I would have to say that my mother was and still is by far one of my biggest supporters. For those of you that aren't familiar with the "special education" system there is one term that students with learning disabilities become very familiar with during their primary school years. The term in question is "IEP." An IEP stands for an Individualized Education Plan. Most students that go through the special education system either get an IEP or a 504 Plan depending on their needs. I myself had an IEP and had to meet with school administrators along with my parents for IEP meetings that were held twice a year. During these meetings we would review my progress in school and decide whether or not the supplementary resources that I was receiving were meeting my needs. At the end of each meeting my IEP would be revisited and possibly revised. Anyhow, knowing how much I lovedddd (*please note my sense of sarcasm here) these rather formal meetings my mom e-mailed me a funny poem that Dr. Seuss had written about IEPs. This was meant to cheer me up and get me motivated for yet another exciting IEP meeting ;)

Anyhow, here's the poem. I hope you enjoy it:

Dr. Seuss on IEPs (1999)

"I do not like these IEPs

I do not like them, Jeeze Louise!

We test, we check,

We plan, we meet,

But nothing every seems complete.

Would you, could you like the form?

I do not like the form I see,

Not page 1, not 2 not 3

another change,

A brand new box,

I think we all

Have lost our rocks,

Could we all meet here or there?

We cannot all fit any where.

Not in a room, Not in a hall,

there seems to be no space at all.

Could you, could you meet again?

I cannot meet again next week.

No Lunch, no prop,

Please hear me speak.

No, not at dusk. No, not at dawn.

At 4 P.M., I should be gone.

Could your hear while all speak out?

Would you write the words they spout?

I could not hear, I would not write,

This does not need to be a fight.

Sign here, date there,

Mark this, check that,

Beware the students ad-vo-cat(e)

You do not like them,

So you say

Try again! Try again!

And you may

If you will let me be,

I will try again,

You will see

Say! I almost like these IEPs

I think I'll write 6,003

And I will practice day and night

until they say

You got it right"

Source: www.ldonline.org/article/Dr._Seuss_on_IEPs

So, I have quite a bit to say...

All week I have been thinking a lot about the topics we have been discussing in class and I've been finding it pretty crazy how much issues around disability overlap with other topics we have been talking about. That said, here I go...

So, much to the amusement of my friends and classmates, I began a story with, "I saw so many disabled people!" this weekend, and it was true! We talked in class about how we have been taught from an early age not to stare at disabled people and we have been too scared of offending them, that I feel like in some ways they have become invisible to us. I know that sounds horribly harsh, but I do think it is true. Sure, we visibly see disabled people, but we don't actually see anything but their handicap because that is what they become defined by. Just last night I was taking a quiz about Grey's Anatomy characters and there was one my friends and I just could not get. When we finally gave up, we realized that that one character was the doctor who was autistic. I'm not saying we forgot who she was because she was autistic, but that our only way of recognizing her was by her disability. But back to my exclamation. I'm not sure if that statement is offensive. Because the topic of disablity is so new to me, I find myself keeping my mouth closed, too afraid to say anything that might be offensive or insensitive. But this weekend, I did see a lot of disabled people. Not just their disability, but them as people. I didn't just look the other way and pretend I didn't see them. Yet, I found myself back in that same situation in which I didn't want to offend anyone by looking at them. Ahh, this can get so complicated.

Anyways, moving on...

In discussions about disablity outside of class, I heard about situations in which people identified as disabled in that, although they were "able-bodied" they felt like one of their limbs should not exist. Sometimes this desire, this conflicting identity, is so strong that they cut off their undesired limb in an effort to become who they "really are." This situation is said to be reflective of a mental disorder, yet I wonder why. Although somewhat disturbing, aren't these people who "suffer" from this "illness" no different to others who feel like they don't belong in their bodies? I don't know...its just something I've been thinking about.

the stare back

(http://www.news.com.au/common/imagedata/0,,6119816,00.jpg)

What I personally find discomforting about this image is that it's really, arguably, no different than any other photoshoot with professional models who give off the same vacant, cold, measuring stare that seems to exert pride about their physical beauty. Their look relays dominance and importance at the expense of others just as any other "conventional" image of model-esque beauty does. It's almost as if someone had simply photoshopped these disabilities in. On one hand, of course its "good" that these disabled models paticipate on the same level in creating an exclusive, inaccesible concept of beauty as do the non-disabled models. On the other hand, their "equal treatment" is still operating within and for an inherently oppressive and devastating system that creates impossible standards of physical appearance which most if not all able-bodied individual would never achieve, much less those with disabilities. So why willingly feed the very system that by and large construes the idea of disability (as a social phenomenon, rather than a purely physical impairment) to begin with?

still all the same?

what strikes me about this photo is how similar they all are. yes, they have varying disabilities, but they're still thin. they're still white. they're still very feminine--the hair, the dresses, the heels, the *pink*. even the spokes of the wheelchair are pink. it's as though the people who put together photoshoots and decide the beauty standards in this society can only handle one sort of variation from the norm--when trying to show "diversity," maybe there will be some thin, normatively beautiful, feminine, light-skinned African-American girls, or maybe a bunch of "plus-size" size-10 women (instead of size-0) who otherwise fit the beauty standards that society has set.

i guess what i'm trying to say is just that what bothers me about this photo is less the "vacant, cold, measuring stare" and more the lack of individuality and diversity. like Karina said, this is "still operating within and for an inherently oppressive and devastating system that creates impossible standards of physical appearance."

"Te Quiero Ayudar"

I don't know what is that intrigues so much about disabilities. I think it's this question that seems to always pop in my head that asks, "why is it that people do not see another person when they see those with disabilities?" and "why do we find some reason to pity them?" But then, these questions always seem to bring me back to women and men. I think that as a society, we function in such a way in which we strive to attain an ideal through what was established as a norm. Although we don't really talk about what precisely that norm is, somehow we know exactly what it is when we see it and when we don't. We see people with disabilities, as well as those who do not preform their expected gender or even those who simply do not fit this idea of the powerful, masculine man as nonexistent and therefore pity them for not having the ability to function "properly."

Even something as simple as a man opening the door for a women or another person doing so for a disabled, can be seen as condescending. Although this is an extreme example, it has been said that people have this underlying concept ingrained in their way of being that tells them that we live in a hierarchical world in which some are better than others. I don't know whether I agree with this or not, but it's hard not to believe in something that you can never know true. It is almost like God and his (using the most common language to describe this phenomenon) being. How do we really know HE exist, if we know we will never know the answer? I don't want to go into depth here, because that is a whole new issue that requires more research, but on a final note, I don't know if we can ever rid ourselves of what has so been life as we know it, but like feminist and activist have set out to do, we must simply try.

This image was taken from:

http://www.studentservices.utas.edu.au/equity/just_talk/Disability/disability.htm

Motion Disabled

http://sweetperdition.files.wordpress.com/2009/01/kickboxing.jpg

Gender as disability

For a larger readable copy look here library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/images/adaccess/BH/BH02/BH0243/BH0243-lrg.jpeg

Notice the use of the word "moisture" instead of blood. This may seem outdated but last I checked people were still saying "feminine hygiene products" and "sanitary napkins/pads."

Here's some other interesting perspectives on the relationship that this aspect of gender (or what people see as an aspect of gender) has with diability.

http://zack16.com/the-film/

If Men Could Menstruate

I just watched the first four episodes in Zack's film (thanks, holsn39!). It made me think of a very short, very funny essay that Gloria Steinem wrote in 1986, called "If Men Could Menstruate." Check it out, for a political edge that Zack's "neat little film" lacks...

Great!

I loved this essay! It was smart, funny, and sad. It had everything it needed to make a strong point. Great!

"Writing provides essential

"Writing provides essential spaces for the future of declaring: spaces that are integral to those expressing their stories. What about the humans who do not identify in this clear, precise, accessible way? For humans who do not fit into the either-or model, the dominant culture’s required structures do not offer us a space. The future of writing our bodies must consider how our bodies speak. This process cannot be a re-imagination of the current writing structures because our bodies do not exist there at all (neither in writing as process or as product). Instead, the process must be imagination as activism. This revolutionary process requires us to be in a constant state of genesis. It asks this question: “What is it to always be in a position of beginning?” The current dominant structure cannot provide any support in this genesis because the genesis depends on what happens when a body does not adhere to the dominant culture’s dogma. In this non-adherence, we have nothing in which to ground ourselves, or root in for the purpose of building our bodies. Our bodies need to be built because they have no genealogy in the spectra of representation in the dominant culture (both in current day and historically ). It is through this active imagination process that we create new positions and methods of declaration."

--- j/j hastain, 2007

I found this except from the website of a Trans activist/theorist/artist. web.mac.com/tjs0108/http%3A__www.jjhastain.com/Transbody_Excerpt.html I thought it was interesting how this could apply to queerness and/or disability.

disability and sexuality

www.sinsinvalid.org/index.html

I stumbled across this website courtesy of www.feministing.com.

On a separate but related note, one thought I had concerning the discomfort people feel in linking disability - especially physical disability, since that's the area in which people get the testiest, most defensive, and most confused - with acts expressive of sexuality and sexual nature is that perhaps it has a lot to do with the definition of disability. Since disability encompasses physical as well as mental disability we have to take into account that (according to the state of Pennsylvania, and many others I'm sure though I can't vouch for them) one of the conditions under which it is actually illegal to engage in sexual relations with a person is if that person is disabled - mentally disabled, mind you. By law, a person who is determined to have the mental capacity of a person under the legal age of consent (or essentially does not understand what sex is and what its "consequences" are) cannot legally consent to sex. So, I realize that a large part of the reason society tends to desexualize people with disabilities is often because sexuality and images of desire depend so much on the "normal beautiful body" deemed appropriate for sex and sexual appeal and which is invariably absent in the case of a person with a physically visible disability. However, I do think that it is not as simple as an "Ew, a disabled person having sex!" reaction. I think there may be something implicit in the act of tagging a person as "disabled" regardless of the details of their impairment that triggers feeling of patronization - a guilt-ridden obligatory sentiment of protectiveness over the physical (and emotional) well-being of a person to whom (in the view of the non-disabled person) life has already dealt a bad hand. Given the amount of stigma and demonization and fear-mongering that surrounds the idea of sex in our (American) society today, it would seem natural for the sentiment of insulting patronization that already plagues the lives of those who are deemed to be incapable of making their own decisions (teenagers, young women...) to apply to and negatively affect the population whose various degrees of impairments have the power to render them those "lesser" than the "normal" population and to bring them down (in Maiers case literally) to a lower level.

In summary: "protect the wholesomeness of our poor innocent children from the implicit evils of sex" is translatable into "protect the poor crippled people, whose bodies just can't take any more abuse, from the evils of sex."

On reforming our "deformed" writing and thinking

I spent a good part of the weekend @ Lynda Barry's workshop on "Writing the Unthinkable." Barry was VERY funny, and also had some great ideas about getting going on writing. Aside from her notion (as cmorias explains) that writing is a biological act, one that involves keeping-the-body-in-motion, Barry invited to us to "go to a piece of paper to find something. Don't worry about not having content before you write -- you write to have an experience" (rather than, say, to record an experience). Writing can be a time when the "drawbridge opens up between the back of the brain and the front of it"; you can develop a "gradual belief in a spontaneous ordering form available in the back of your mind." I think a lot of Barry's exercises would be useful ones for all of us, for getting ourselves started on writing analytical essays, as well as creative ones, and I hope we can try out some of them together as a class.

Two interesting counter-moments, though, that I also wanted to put on record here: At the very end of the workshop this afternoon, when both Barry and a number of the participants were getting a little punchy--@ that point of exhaustion where we are "made happy by anything"--a participant read a description of an early childhood friend born w/ a deformity, and there were lots of gaffaws. That connected for me w/ something Barry said @ the very beginning of Saturday morning's session. Emphasizing her point that we should NOT read over our writing during the workshop (in order to prevent ourselves from commentary, from thinking and editing), she said, "Don't read over what you've written, asking fretfully, 'Is my baby defective?' Just keep on writing, and don't look back!"

So: I haven't thought this through all the way yet, but it seems to me that there may be a troublingly useful analogy operating here: just as we may think of people who are disabled as being "deformed," Barry was similarly inviting us [not!] to think of the imperfect first drafts of our writing as "defective." Both sorts of thinking are hampered by a notion of the "perfect," of the "ideal," of the "norm" that I think we might usefully re-think (and re-state! and re-write!).

I've also been thinking a

I've also been thinking a lot about how Lynda Barry's speech/workshop relates to this notion of a comparative norm and the "deformed." I loved how we weren't allowed to read over anything during the course of the two day workshop - especially because I'm the kind of writer who compulsively checks over each sentence and edits/criticizes myself. It's weird how I never realized how paralyzing that process could be! What Barry called the voice of "rationality" but we could also call the sense of a "norm" or "standard" completely restricts one's freedom of expression by the anxiety of checking back and retracting and erasing. I think this philosophy is relevant in many contexts outside of writing, as Anne states. I was thinking about the moment where she brought up how most people used to sing but once they heard Frank Sinatra's voice over the radio, they said, "Oh, so that's how it's supposed to sound!" and people stopped. While I don't know how accurate this anecdote is, I think the idea is crucial. Once a kind of standard is publicized, then people feel that they should be ashamed if they don't match up - if you can't sing like Frank Sinatra then you must not be a good singer. So I guess I'm getting a little bit away from the discussion of disability, but I do think that the ideas are related. One cannot be marginalized until a norm is established. Lynda Barry's solution to this voice of "rationality" or "normalcy" was to think about it like this (and i'm paraphrasing):

You're drawing a picture and a voice in the back of your head says "that drawing sucks. where's drawing going to get you in life?" You call that voice the voice of reason. But think of it this way - you're sitting in a bar and you're drawing a picture on a napkin. Some guy walks up to you and says "that drawing sucks. where's drawing going to get you in life?" What an asshole, right? You'd want to punch him right in the face. So think about that voice in the back of your head like the asshole in the bar, tell it to shut the hell up and keep drawing!

I feel like we can apply this lesson to all the voices that tell us how to define perfection or normalcy or an ideal or on the negative, whether you are deformed or a freak or less than. It's something external that comes from a social construction - it's just the voice of some asshole who thinks he knows better. Everything that you express has an inherent value that has nothing to do with a standard.

"The voice of reason might just be an asshole."

For me, too, one of the strongest of Lynda Barry's (many quotable) lines was "The voice of reason in your head might just be an asshole."

And yet, and yet....

as I (use that voice of reason to?) think back over our workshop, and as I discuss and process my experience with colleagues who were also there, I'm increasingly aware of the absence of the crucial editor, that part of writing that must--if we are to communicate with others?--come after the untrammeled brainstorming that results when we let down the drawbridge to the unconscious. Yes, we are, as Barry says, "all natural writers" (though see holsn39's intriguing challenge to that claim, on the limits of current writing structures for humans who do not identify in "clear, precise, accessible ways"). Certainly Barry's repeated "good! good! goodgoodgoodgoodgood!" is a voice we all need to hear, and hear again. But @ some point the editorial voice needs to kick in again, and it's increasingly striking to me that Barry didn't let that voice into the workshop (and so, for me, left the process incomplete).

so i posted this on the wrong forum by mistake =S

i found a fw iteresting image last week but i posted them on the 'outside talks and events' forum by mistake?

anway, here they are.

essay extension

playing with words

what are we looking for? what are people looking for in us? words words words.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9qiCjREzhYE

some random thoughts

First off, I sort of came up with this design for GaS, what do you think? If anyone wants to add/change it, please do so!

Secondly, I don't really have any complete thoughts right now, so bare with me as I ramble:

-I would be interested in going more into mental disabilities, but I understand we have limited time. The idea of "Mad Pride" definitely intrigued me.

-The movie "Coming Home" (http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0077362/) came to mind when we were talking about disability and sexuality. I remember hearing it was shocking to audiences because it included sex scenes with someone in a wheelchair.

-Also going off the disability and sexuality topic, I thought it was so intriguing that disability could potentially open up sexuality and make it more fluid for someone because they couldn't necessarily play into tradition male/female sex roles.

-We're talking a lot about disability in terms of art (writers, painters, dancers, etc.), I would be interested in taking a look at the everyday of disability too.

That's all for now!

Analogy

analogy: When I first started thinking about Gensex compared to disability my first thoughts were more focused on the differences between the two identity categories. When Kristen pointed out Roughgarden's quote "I wondered where we might locate diversity in gender expression and sexual orientation within the overall framework of human diversity. Are these types of diversity as innocent as differences in height, weight, body proportion, and aptitude? Or does diversity in gender expression and sexuality merit special alarm and require careful treatment?" Although I didn't agree with Roughgarden's judgment of disability as "innocent" I think I understand where she is coming from. The thing about disability is that it is generally accepted by society that disabled people aren't "choosing to be disabled" and that they can't be blamed. (this doesn't mean that people don't see disability as "wrong", but they try to excuse it.) But those who chose to take on identities of gender and sexuality that don't go along with hetero-normative expectations are subject to a lack of acceptance of another kind. People still seem to think that we choose to feel like they are gender variant or non-heterosexual and therefore don't deserve 'compassion' or respect. It think both of these societal reactions to different identities come with various disadvantages of their own. Neither forms of diversity should be seen as innocent, and both deserve special alarm and careful treatment.

After thinking about these types of diversity I started to see their similarities. If indeed gender and sexuality isn't a choice (what we're expected to be and/or what we are) then they may be regarded differently from disability by other members of society in some ways but also very similar. When I look at myself I see my gender and sexuality as my greatest disability in terms of my ability to obtain power in society. When I say power I am talking about monetary, physical, political, etc. But personally, they are not disabilities because I love myself for who I am, I see my gender (not binary) and sexuality as qualities. And I think that disabilities, physical or mental, are also qualities to every person, even if they disable them in society.

more paired images.....

Like (I think) many of you, I have been mesmerized by the sequences of images Kristin has brought into our conversation, and by others that you all have added to the mix. Here are a few more.

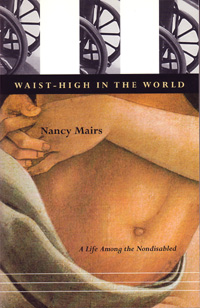

The first is the original painting, from which the cover of Nancy Mairs' book was excerpted....opens up many more possibilities for interpretation, yes? Can you see where the "waist" came from? Would you say that the image on the cover of that book "crips on" Botticelli's original image?

The second pairing is of two images that turned up, two years ago, in the Critical Feminist Studies course that Melinda and I did together. Commentary from some of the students follows (inviting, of course, more from you all....)

[From Continuing Our Discussion of Disability....]

Lakshmi's surgery completed successfully

lvasko: what western cultures consider a "disability", another culture could consider a blessing....Lakshmi, aptly named after the hindu godess of prosperity, is being worshiped as a godess in her hometown.....our conversations about Feminist Disability Studies...may not apply to other cultural traditions.

gammyflink: This is not just a matter of appearance....."The complications for Lakshmi’s surgery are myriad: The two spines are merged, she has four kidneys, entangled nerves, two stomach cavities and two chest cavities. She cannot stand up or walk."

jrizzo: I'm not sure I see what is so terrible about favoring normalizing surgeries when the disabled do now typically have a more difficult situation than those who are not. To say nothing of legitimate health issues, having some visible deformity and attracting The Stare....People stare at things that are different. Sometimes gawk. Sometimes it's very impolite, but the unusual does attract attention.

kwheeler08: What is important to take from this article is the idea of the cultural constructedness and the arbitrariness of the definition of the term "disability"....Individuals should not have to change to fit the "mold" of society; instead society should change the mold (or rather get rid of it all together) so as to accept people of difference.

humorous, if disturbing

This showed up on FAIL blog, and I thought I'd share. It's a website where people take pictures of people "failing" at things, like misspellings or examples of bad parenting, and this picture is definitely a "sensitivity fail":

link:http://failblog.org/2009/10/22/sensitivity-fail-2/

as far as talking about

as far as talking about disability goes, im afraid my thoughts are all over the place. i dont completely understand how it links to gensex. yes it does as far as identity goes but then doesnt almost everything under the sun? dont get me wrong, i love that we're studying it, i just.. im not entirely sure why we are.

i do like that we're covering it. its fascinating because ive never thought of it before. but i agree with cantalope, while watching the videos, i wasnt reacting to the peoples disabilities, i was reacting to what they were doing. ive never categorized physically disabled people, i dont think i pity them or look at them differently. to me, they are on the same level as any of us.

but even as i say this, i find myself thinking 'but i do respect them..' and there it comes, the 'them'. 'they' are now a category. good thing? bad thing? im not sure.

having said this though, like a lot of other people, im still playing with the word 'disability'. is someone dealing with depression/schizophrenia disabled? am i disabled in india/the world because im a girl? do i become further disabled if i decide to identify as gender varient? is there anything like further diabled? or are you just disabled - without any degrees.

as you can see, i have no clear ideas at this point.

x

we'll all be disabled one day

we're all trying to compare disability to other 'categories', for lack of a better term, and yet it seems to be harder than simply equating disability to homosexuality, for instance. i think that maybe the concept of disability, though it may divide and potentially limit in the same way, is different because of our personal relationship with disability. each of us will most likely, one day, be disabled, as someone mentioned in class. even if nothing tragic, sudden, or otherwise drastic occurs to disable us, and even if we are born 'perfect' (loaded term, i know, bear with me), the toll of living for an extended time will get to us, we will age, our bodies will deteriorate, and we will no longer have the abilities we have now, in our 20's, wherever those present abilities may fall on the proverbial spectrum. this being the case, i think that part of how we relate to disability is not just in comparing people to a societal norm or even ideal, but in comparing the potential for our own disability to our ability - what is the norm for us. realistically, there is no chance (that i know of) that one day i could wake up black or a man. i never have to think of 'being black' as a potential future experience of mine. realistically there is a chance that one day i will have lesser abilities than i do now, potentially even drastically so. this is a key way that i think disability is separate from race/sex/etc. yes, one day you could be in a different social class, but this is not permanent, and the american dream promises that we will always be able to move upward and forward if we just try hard enough. this same attitude does not exist with disability. even if some levels of disability are transient, there is not the same 'you can fix it if you work hard enough' attitude - its out of your hands. even being gay, enough people still debate the nature/nurture, that i doubt the 'average' straight person goes to bed and thinks they could rather conceivably be gay outside of their control tomorrow - there is still a perceived mutability/choice involved. disability is a potential for everyone, and let's be honest, not something that people look forward to, or even want to accept as a possibility always. you're young, your body works great, your mind is sharp, and nothing will ever happen to that right? even if you start off squarely in the abled category, someone mentioned gattacca, it doesn't mean much in the long run. i'm sure that has something to do with our attitudes towards disability.

disabled as a category

I'm intrigued in this study of disabled people we are embarking on. It is something I have never considered before, so I'm not sure that disabled people as a study is a good thing or a bad thing. In a way it is good because it's making me look at a section of people in society I haven't given much though to, but at the same time if I didn't give it much thought before, is studying it now just categorizing it more in my head? I previously thought of disabled people as just members of society, not a "group" of people, but now I am looking at them as their own group. It's similar to our discussion about the fact that we study women seperately makes it impossible for women to just be part of society. Regardless, I'm still intrigued.

I feel like I'm on a different page than other people in the class. When we watched the clips in class I laughed because the jokes were funny and I watched people dance because they were dancing. It didn't shock me to see a person dancing in a wheelchair. I didn't feel "bad" about laughing at the jokes someone makes about his own disability. Even in the streets, I don't stare at someone in a wheelchair, feel bad about staring so I stop staring, but then stare again because it's so shocking. I'll look just like I'd look at any other person on the street.

Rae commented about the PCness of calling someone disabled and it struck me as kind of funny. Society (and maybe our class as well) is so worried about offending people. I really like that disabled people are reclaiming the term crip. The ability for a word to be offensive is made by the people who decide it's offensive. If disabled people decide crip is no longer a derogatory term, then it isn't. It's like how gay women reclaimed dyke.

The part I am most interested in for this unit and what I'd like to write my paper / do some kind of formulation of thoughts in any kind of creative manner is on the deaf community. I've always wanted to learn more about how a deaf person interacts with the world. I've wanted to learn sign language for years (and still intend to one day). I really liked watching the signed poem. I had no idea that signed poems have a form of their own. I'm looking forward to reading more about it.

I'm a PC person :(

I definitely agree with cantaloupe, but I have to admit I am one of those awkwardly PC people. I have thought a lot about why I’m so afraid of offending people, and I guess it is that I simply don’t want to make others uncomfortable. I acknowledge that progress is best made during conflict. When people are able to be critical and even confrontational, people are made uncomfortable. I think this discomfort comes from a deeper sort of fear of being wrong. A feeling that “damn it. I’m going to stick to my guns because this is what I thought and it’s shameful to be wrong”. Which may have something to do with early education using the word “wrong” for both bad behavior and incorrect responses on simple exercises. I feel a certain shame in being “wrong” is ingrained in most people and as scholarly thinkers we have to overcome this conditioning. As outdated as some of Sherry Ortner’s opinions were, I think we can learn something from her willingness to rethink her own, published opinions. If she can do this why can’t we accept confrontation and the challenging of ideas as just that- challenging ideas, not people? As I make this argument I consider changing “we” to “I” because I don’t want to offend anyone by including them in this group wrongfully… I think a possible solution would be calling each other out in class, or in the forum when we think we are being overly PC. Not as a personal criticism, but rather as an attempt to elevate the discussion in the course.

coupla' more cites...

...I'd like to add to that wonderful bibliography Kristin generated; these 3 pieces have been

very important to me in teaching all sorts of courses about category-making and -bending:

Institute for the Study of the Neurologically Typical

Culture as Disability, by Ray McDermott and Hervé Varenne

--as well as a follow-up essay (generated by Paul Grobstein's question, "can

there be a culture which does NOT disable/disadvantage ANYONE in it?")

Extra burdens in the search for new openings; on the inevitablity of cultural disabilities," by Hervé Varenne

thinking

I guess like others I'm most curious to find connections between disability studies and g&s studies. Terrible2s mentioned the definite thematic links and anecdotal connections, but I'm looking for something further than that.

I feel very new to this subject, and I seem to simultaneously have all these thoughts and questions reeling in my mind and nothing to say. I didn't get into the Davis reading, but I loved the Thomson reading and I cannot wait to get to the library and dig through the books Kristin listed in the bibliography. I still don't know how I feel about gender or sexuality as disabilities, though I'm intrigued by the discussion of it.

We read Exile and Pride by Eli Clare in Theresa Tensuan's Arts of the Possible class last year, and I remember a passage I really loved in the book: "Disabled. The car stalled in the left lane of traffic is disabled. Or alternatively, the broad stairs curving into a public building disable the man in the wheelchair. That word used as a noun (the disabled or the people with disabilities), and adjective (disabled people), a verb (the accident disabled her): in all its forms it means "unable," but where does our inability lie? Are our bodies like stalled cars? Or does disability live in the social and physical environment, in the stairs that have no accompanying ramp?" (Page 67). He goes on later to say that he understands his relationship to words like these: handicapped, disabled, cripple, gimp, retard, differently abled.

HE is very much a capable person, even though others didn't (don't) view him that way, and it's only because of other peoples' perceptions that he had to form a relationship with words like "gimp" and "retard." I'm angry about this; I'm angry that there is an "ideal" body dictating how people treat one another when approximately 1% of our population fits the "ideal." And while I believe that there is something different about "normal"--the ideal is an archetype, a construct we've made while normal is the standard, the ordinary...akin to "average"--it isn't much better. The normal is as good as a number, it's a statistic, and what does that mean? But when we have outliers that fall beyond the normal broken down into "good" and "bad" or "inspirational" and "shameful," we face a problem similar to the problem of the "ideal."

actually, maybe they would say mixed-race...

Kristin mentioned in class today (in reaction to the mixed ability dance company, or theatre, or whatever it was) that people wouldn't say mixed-race. and while i think that that can be problematic (that there is such emphasis on different abilities and that differently abled people are immediately considered "other"), i think that in this case, it might not be a bad thing, or at least not as bad as it could be.

there's actually a theatre company called Mixed Blood Theatre Company (www.mixedblood.com/about/) that is about multiracial theatre. i think that there's nothing wrong with having something that...is aimed at a certain niche. maybe like a women's college, or a historically black college, or an LGBT choir--allowing people to have a space where they can celebrate who they are can be a good thing. however, i think it's important that it's intentional. a mixed ability dance company that markets itself as such in efforts to promote diversity and showcase the talents of those who are differently abled, or something like that, is very different from calling a dance company a "mixed ability dance company" because someone in the company happens to be disabled. does that make sense?

by the way, i guess i don't really care about political correctness for its own sake, but i do care about not being offensive, so is "disabled" okay to say? is "differently abled" too unnecessarily PC? what term should i be using?

South Park

In class when Kristin told us about the reclamation of he term Crip, I couldn't help but think about this episode of South Park (here is the link). In the episode, Jimmy and Timmy try to start their own group for crippled people which they call "The Crips" they later find out that there is already a group called The Crips and end up joining the gang. Anyway the episode touches on a lot of different topics related to disability. I just thought I would put it up in case anyone wanted to watch it. It might be interesting in thinking about the way disability is dealt with in different areas of popular culture.

fix that link?

it's to "dwarf tossing," not south park...

After class I started

After class I started thinking about the fetishism of disability in comparison with various other fetishized groups.

This is a picture of a group of primordial dwarves appearing on the Tyra Banks show where they recieve makeovers and iPod minis. It seems to me like television shows featuring people who are in some way disabled are becoming more and more common (probably because TLC seems to develop a new one every month). Is it possible for a television show, which is by nature so higly commodified, to be anything other than exploitative. This type of show is typicaly framed sensitively, often the subjects are shown saying something about how grateful they are to be given an arena to show who they are as people and shed some light on what living with their disability is like. Still, something about this type of programming seems like a modern version of a freak show, revamped so that the observer is free to gawk privately.

Also, did you know that at some bars you can pay to toss a dwarf wearing a velcro costume onto a velcro pad? Its called midget tossing. I've been thinking about the relationship between this and other activities in which the body is the spectacle i.e. stripping.

I am still thinking about both of those things and about fetishization more generally, my thoughts are still not fully formed. I am curious to know what you all think/feel.

Disabled and Dismayed

So today's class was so interesting to me. I love learning about different cultures, but rarely have I learned about "Crip" culture. I love that, by the way (as much as an outsider to that community can). I also find it so interesting how many shrouds of taboos and stigmas we have to get around to talk about this stuff. Can I say that I love the term "Crip"? I especially enjoyed the video clips mostly because they did what any art form should do--they made us uncomfortable. I was thinking and questioning myself, staring, looking away, enjoying myself and somehow feeling guilty.

Did I feel guilty because I in someway pity these people? Do I find myself in some way superior? Am I just as flawed but we define "normal" in a way that I somehow feel that I am "disability-free?"

Which brings me to my next question. I'm also wondering, like Anne's second question, where are G&S and Disability studies linked? I get that there are definite thematic links, and I'm sure plenty of anecdotal connections (queer people with disabilities, etc). However, I just don't see why this unit is any different from picking a random life-topic and finding its connection to G&S. G&S are an integral part of human behavior and therefore can be tied to anything. This unit is so interesting, don't get me wrong, but I'd be interested to know more of the connections.

That being said, I'd like to touch on what some have already spoken about: gay as a disability??? I find this topic so interesting. Basically, it can be argued that God (or whoever,) put Adam and Eve (or two random people,) on this earth. They procreated. Those offspring procreated. Their offspring procreated. So on and so forth. "Adam and Eve not Adam and Steve" they say, to prove that God intended for us to be straight. It's an interesting arguement. Penises and vaginas fit (for the most part) and intercourse is the only (known) way of procreation. SO is any deviation from that in fact a variation from the "norm"? Could we go so far as to call is a disability? How about intersex people? Mostly, we're born with one set of junk, corresponding to our XX or XY chromosomes. Some aren't. Disabled? Who knows?

Anne said that perhaps the the Disabled Community or Crip Community would be offended by gender being called a disablity. How about the queer community?! Am I disabled because I identify as queer? If I really think about it, it definitely acts as a handicap. There are many things that I could be barred from doing or being because of my identity. So then how far do we take this? Is race a disability? Height?

I have a gay friend who comes from an orthodox Jewish family. Obviously he has had many struggles in finding and defending his identity to himself and his community. After much thought and fighting, his very religious father came to the conclusion that he would except his son. To him, it is clear; his son has a disability. There is obviously something wrong with his wiring, and any other queer person for that matter, and it cannot be helped. So he supports his son, and the queer community, but encourages them to associate with each other so as to not offend or upset the "normal" bunch. My friend's just happy his family didn't disown him...

What can we make of this?

a few of my many, many questions!

Some of my (many, many) questions about this really interesting and important field Kristin is guiding us into:

1) "Cripping" is a neologism for me. I don't know what it means, and I want to (please).

2) I want to think more about the intersections between the two different sets of "identity studies" that are g&s and disability. Are they analogous? "More" than that? Where do the parallels break down?

Is gender (for example) a disability? (Kate Bornstein, whom I'm madly reading @ this point, certainly thinks so: she says it limits the full range of self-expression). Might a disability rights activist take offense @ such a claim?

Along this line, you all might be interested in a recent gritTV show about "the bullying of Casper Semanya." One of the guests says that all athletes are freaks of nature (large feet, long limbs...) but that the Semanya case only became a sensation because her freakishness was gendered, or rather gender-bending....

Okay (deep breath; not done yet; I AM engaged by this subject!!).

3) I would also like to think more about Lennard Davis's claim that "the novel as a form promotes and produces normative structures." I spend a lot of time thinking about genre, and I am a decades-old novel lover, so I am particularly curious if this is an action particular to the novel form, or....?

4) Contrary-wise, I was struck today when Kristin how many disability memoirs there are. So now I'm also wondering how that genre works in disability studies: it certain provides individualized accountings of individual lives. But then how theorize, or generalize, or act (we've been talking so much about activism...) ? What are the advantages, in other words, and the limits of the work that that genre can do?

Okay, I'll pause for now. More later!

A.

A quiet presence of disability in the past present and future

I was interested in what Anne had to say about someone saying something to do with percieving "gayness" as a disablity. I then thought about how people percieve things such as being over weight, too tall, too short, etc. as disablities as well, which then makes what people might call "severe" physical disabilites be seen as much more problematic. If differences such as sexuality, height and weight can be viewed as disabilities in "marked bodies", other more severe physical disabilities seem "grotesque" when they are not. I believe that this view on disablity is the reason that it is not talked about at length in a lot of open forums of discussion, it is the reason that it is still an up and coming field of study.

Because a lot of our society is so obsessed with obtaining the "ideal" body (which I do see as different from normal that I think of is more of an average), people are very uncomfortable talking about what is outside the "norm" on the disability side. It is telling of our society that disability is still not widely talked about and how Kristen mention that eugenics is still very present. This got me thinking a lot about dystopian novels, movies, and other portrayals of where our future is heading. In "Brave New World" people are classified by castes that are presubscribed to them by getting rid of natural reproduction and impeding people of the lower castes to have mental and physical disablity through chemical interference. The different castes don't interact with each other and everyone is ambivilant to the way their society is structured. This futuristic society shows the problems of present society (even thought the novel was written in the 1930s it is still very relevant) with disability on an exaggerated scale, but it is not too far off from where we could easily go in terms of diversity in the future, particularly with disability. The movie "Gattaca" was also brought to my mind where the society portrayed allows humans to choose the genetics of children before they are born to reduce disease and other "unwanted" genes. People who are natural born are seen as lesser. This take on the future of our society once again shows how much present society really does not know how to deal with disability or varience in any way and that's a scary thought. I hope that made a little sense and is applicable to our conversation...

silencing and self-definition

This relates some to what Prof Dalke mentions above, but reading Davis's article, I was most intrigued by the parts in which he speaks about the formation of the idea of disability as something to be fixed or cured. The voices who are making these decisions are of course the people with the most institutional power (i.e, people who fit society's construct of "normal"), but the social definitions should really be made by people whose life experience is what's under debate (Mairs, for example). I'm interested to learn more about how people of various disabilities self-define - the deaf community, for one, and the concept of Capital-D-Deaf Culture vs. the societal idea of making deaf people hear, etc.

I'm also randomly reminded of a piece I read in TIME (?) a while ago about a man with autism who was an activist against Autism Speaks because of the way the way they treated actual autistics (really poorly). Kind of hilarious to see in a magazine that tends to sensationalize and silence anyone who is remotely outside the "norm", but there you go.

On not having to be cured

These readings have altered the way I am looking @ the world. I was telling Kristin that last Sunday I went to Central Philadelphia Monthly Meeting. Early into the Meeting for Worship, someone told the inspirational story of having heard a magnificent pianist in New Orleans--who had a club hand. Then someone else stood and spoke of how similarly inspired he was to hear another famous pianist play @ the Kimmel Center, here in Philadelphia--w/ only his right hand--after a stroke had incapacitated his left one.

Rather than emphasize the distance between spectator and spectacle, as Garland-Thomson does, these messages were all about how "miracles can happen": the triumph of [the human] spirit" in which we can all participate.

So: I was sitting there stewing, thinking of how I could give an *appropriate* (i.e. not lecturing/teaching/shaming) message about the first of the "rhetorics" Garland-Thomson describes: that pre-modern construction of the "wondrous," "courageous overcomer"...

...when another f/Friend stood to muse about how much the stories in the Bible are actually the stories of each of us. He'd heard a talk about gender varient people in the Bible, in which Joseph was identified as transvestite (I'm going to have to check that one out....). And then he described his boyfriend, a "'deaf-mute' who is not @ all mute" --wondering if there are disabled people in the Bible who do not have to be cured, who are alright as they are.

And so: message given.

maybe

whilst davis' historical perspective on normalcy and therefore abnormality was insightful, i have to admit it didnt intrigue me. maybe it was because i found his style of writing dry or maybe because i feel like although the history of the problem is important, it isnt the problem and therefore his article provides just a background and not so much a perspective on things.

disability and body image topics just seem so relevant today, and i think that it might have been easier for me to delve into what he was saying had he been talking about what he felt more than how things came to be the way they are.

maybe im still just stuck with the humanities and am being stubborn about it.

however, one thing i really liked was when he wrote (and i quote): 'the corpulent, lazy body of Verloc indicates his moral sleaziness' it brought back memories of my mother telling me to 'carry myself well' because it portrayed my character. and i guess the way you walk (back straight, looking up vs. slouching and dragging your feet on the groud) does affect the way someone would form an impression about you, but does that mean that body language is just something we've been conditioned to believe?

is it?

i know our minds play a role in the manner in which our bodies function. but is part of that role something we've been conditioned to feel/think?'

hmm.

Davis & Mairs

It was so interesting to see such a comprehensive geneaology of what Davis calls the "hegemony of normalcy" (49). A parallel idea that Davis mentions in the article is that of the perfectable body; he describes the effort inspired by those involved with eugenics to attempt to "control the reproductive rights of the deaf..." (32) as a means of trying to eliminate that trait in later generations. This idea of a perfectable body has seemed to resurface time and time again in different ways. We see it now on the covers of different tabloid-y magazines or something like Men's Health (I work in the bookstore at HC so when I restock the magazines I always notice how repetitive the magazines tend to be): ways to build muscle or lose weight or any number of things. So there's this idea of a "normal" body that isn't just normal. It's unhealthy. To make it even more complicated, the "normal" body is different by gender, race, class, etc., so the means and lengths that people seek out to achieve the "normal" body vary incredibly. Even then, it is assumed that these bodies are "normal" in terms of their ability: they can see, walk easily, hear, don't have any trouble reading, can stand or sit up straight, etc. As I've been reading Mairs, I have seen how I take for granted some days that I can walk easily, etc. Mairs is particularly striking though in her essays because of the sense of independence she conveys no matter how limited her physical mobility may be at any given moment in her narrative. She refuses to concede her agency, and this comes through in surprising and thought provoking ways. In "Taking Care," she describes how she thinks twice after she showers herself, dresses herself, and feeds herself after her sister and her husband have a miscommunication. She holds herself accountable for being responsible for her physical safety (not being too ambitious), for find ways to care for others (letting her husband go on a trip and accepting help from her mother), using her experience to encourage and help others, and using her writing as a way of "taking care."

Basically, these readings gave me a lot to think about, and a new way to think about the world around me.

Mairs

Rereading Nancy Mairs this week, I discovered that I still find her writing about disability compelling (a decade after first reading this book) but I was also struck by how heteronormative her assumptions are. Scholars and activists working in disability studies and disability rights often point out that people who are enlightened about diversity when it comes to gender, race, and class make all kinds of benighted assumptions about disability. For example, they fail to see disability as an experience that involves identity, diversity, and rights (not one that simply elicits pity and charity). Nancy Mairs knows a great deal about disability, but I wish she were more attentive to diversity in gender and sexuality. It's a reminder to me that we need to be persistently curious about other subjectivities, other perspectives, other experiences.