Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Mental Health and the Adapting Brain

|

Mental Health and the Brain:

|

|

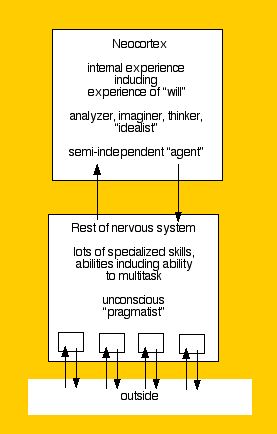

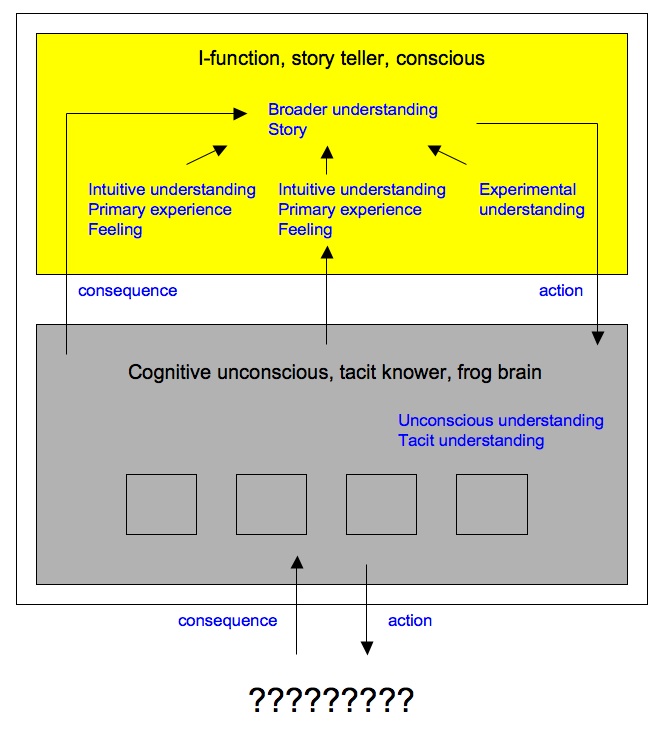

Our fourth session and resulting on-line forum discussion seemed to make it possible to locate "mind" in brain, and, in so doing, suggested that the brain could be usefully thought of as subdivided into two parts, a cognitive unconscious or tacit knower, and an I-function (consciousness or story teller), with the latter getting inputs from and acting through the forumer. This in turn raised a number of new issues relevant to thinking about mental health (to say nothing of human life in general). Among them is the degree of interplay between "unconscious" and "conscious" processes, the subject of our upcoming discussion.

Readings for this week

- Making Sense of Understanding: The Three Doors of Serendip (be sure to do the activities provided at /exchange/threedoors/door1 and /exchange/threedoors/door2a)

- Interior Grounding, Reflection, and Self-Consciousness

Relevant new things elsewhere ...

Psychoanalytic therapy wins backing

- at one point it says, "The field has resisted scientific scrutiny for years, arguing that the process of treatment is highly individualized and so does not easily lend itself to such study." Psychotherapy is highly individualized, but on the other hand that makes it seem like pharmacotherapy is/should be straightforward when it in fact seems to be just as highly individualized as well. ... LauraC

- But CBT and DBT, etc. programs are often less individualized, at least as treatment models. (Though often also more strictly time -limited, and easier to do in groups -- so cheaper, as well.) ... ysilverman

Bailout provides more mental health coverage

- "a milestone in the quest for civil rights, an effort to end insurance discrimination and to reduce the stigma of mental illness"

- I am glad it went through, but do people really see a need or are they just concerned about losing $$ ...merry2e

- how relates to course? can we all pack up and go home? See "gained widespread support for several reasons ..."

I am a big fan of this being the 'unconscious' we so often discuss. Lets take something like flirting for example. All of us know how to do it (to varying degrees of success) but certainly no one has taught us how ... akerle

I can relate to the basketball player example from class ... trying to get out of her awareness, and her consciousness, to a place where she can focus without being so overly stimulated and aware. I try to do this when I play tennis, except a lot of the time, I end up failing. ... It's when I become aware that I need to escape that I know I'm already in trouble, and maybe that's a general part of the awareness part of the conscious ...kgins

I think I have been trying to modify my unconscious understanding with

respect to my sport, horseback riding, for some time. When I am

approaching an obstacle or jump on my horse, I unconsciously ask her to

move up, or increase her impulsion and lengthen her stride. This is

entirely unnecessary ... Why do I do it then? Because my older horse,

does require those signals in order to correctly clear a jump. Sending

those specific signals to my horse has become a habit for me ... jrlewis

I was musing to Judie that her story of the tripartite brain might prove more "useful" than the account Paul had given of two severely separated sections of the nervous system-- more useful because it actually locates a third "place" where therapy and change can occur ... Anne Dalke

My unconscious feels very inaccessable so it makes sense to me that a preconscious is needed to facilitate communication between my conscious and unconscious ... Riki

In applying this question to mental health, the tripartite brain then says that at some (very real) point people’s attempts to control their actions are futile – the conscious mind simply cannot expand its power further. However the bipartite model doesn’t necessarily have such a problem. It allows us to say yes, the large part of our actions may be unconscious, but that does not mean we cannot learn to be conscious of them and thus consciously change the unconscious ... kmanning

Unconsciously, the body starts to slow down; but consciously, you can train the brain to keep the muscles working and the body moving quickly, despite the feelings of fatigue ... mstokes

when you are looking at the ballerina silhouette and she flips for the first time, you don't really have any control over when that first flip happens, but then you can start trying to flip her back and forth and you can get better at "seeing" her move in one way or another ... Ljones

I though the idea of “relationship schemas” in our unconscious really

underscored how these two parts of the brain must be related. If our

unconscious is facilitating our interactions with others, I feel that

our conscious could be made aware of these schemas at some point

through observation (and therapy?) ... Paige Safyer

What I think of as "me" when I say that word I mean all of me, not just my brain or a part of that brain ... Martin Bayer

Christopher Reeves might feel like the toe we pinched was "his" toe... but I'm not sure if it is a part of "him" so much as part of something he owns ... Ljones

This notion of “containing multitudes” is one, for me, that gives texture and meaning to experience, to life, to interactions. I think that multiple “realities” are necessary in order to truly conceptualize the breadth of human experience, both to reconcile conflict within oneself and to understand similarities and differences in perceptions amongst people ... Sophie F

I agree with Martin that claiming multiple realities can unnecessarily complicate things. However, I also agree with Sophie that multiple realities add texture to life and are necessary to fully conceptualize the breadth of human experience ... ryan g issues:- multiplicity

- self

- interactions of unconscious/conscious

- change

Continuing the bipartite brain and "mind"

- the blind spot

- blind sight, spastic paralysis

- pain, phantom limbs, emotion and feeling

- eating behavior, moods, sleep and dreams

- implicit, explicit memory

- the "cognitive unconscious": characteristics/capabilities/limitations

- the story teller: characteristics/capabilities/limitations

- morality

- multiple realities within one brain - Capgras syndrome

- the bidirectional interaction between the cognitive unconscious and the story teller

- originates in unconscious, in processes of which we are unaware

- could be otherwise

Adding change/progress ...

The loopy brain (parallel to loopy science)

unconscious learning -> multiple continually updated tacit understandings (loop 1)

limitations of "getting it less wrong"

- no assurance of coherence

- no way to move beyond implications of local experience (the local maximum problem)

the story teller as synthesizer, amplifier of exploration, also "getting it less wrong" but with unconscious as input source and unconscious among testers, new possibilities

- limitations of the story teller

- too great a concern for simplicity, logical consistency, certainty

the bidirectional loop between the unconscious and the story teller (loop 2)

- conscious influence on behavior that in turn alters unconscious over time

- direct influence of story on unconscious

Problems of loops as problems of mental health?

Mental health as effectiveness at ongoing exploration/creation? freedom/wherewithal to create new meaning? being able to enjoy the certainty of the unknown?

The interpersonal as a third loop?

Your thoughts in forum below ....

Comments

brain injury and sense of self

For more on capgras syndrome, see After injury, fighting to regain a sense of self.

Food for Thought

I also spent a lot of the break trying to figure out whether I agree with Dr. Grobstein’s assertion that human beings when compared to other organisms in the world are not superior. I have always believed that we are not necessarily superior in the sense that we are more important than other organisms, or that we have the right to take what we want, regardless the consequences. However, I do feel that the human brain as an organ is far more advanced any other currently known organism. This is not the spiritual side of me speaking but the scientific one. A part of me wants to say that many of the mental health issues that we have addressed thus far stem from our mental superiority. The stresses of everyday life, the notion of worry (unique to human beings), the need to support ones self and ones family, our social constraints (monogamy, children, cultural beliefs) are all concepts of organisms with superior brain activity and in addition more complex social constructs.

I am not arguing that animals do not feel stressed, but from what I have read and observed most of animal induced stress is triggered by human intervention. These are just rambling thoughts, but I wanted to get them out so if nothing else I can understand what is going on inside my own head.

I found Riki’s post very interesting, especially the following comment: “With depression, one doesn't always know what's happening or why one feels the way they do, which implies a disconnect between conscious and unconscious.” In tenth grade I suffered from severe bouts of depression and through a combination of different therapeutic approaches was able to understand and control it. I used to experience intense feelings of sadness and disillusion for absolutely no reason. My feelings did not correspond to really anything that was going on around me. Through therapy I taught to recognize the onset of such feelings and learn not only to ignore them but also to combat them with either intense exercise or other endorphin boosting activities. There must have been a disconnect between my conscious and unconscious, but which was I teaching myself to override?

Autism

Autism

This is a link to an article, appearing in Sunday's NY Times, about working with autistic teenagers. I was struck by the description of a new approach to working with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) called D.I.R./Floortime (developmental, individual differences, relationship approach). The article states, "... it is an approach that encourages students to develop their strengths and interests by working closely with one another and with their teachers." This reminded me of Professor Grobstein's definition of mental health, which entailed, in part, working with people's strengths to develop them and shape meaning around those things rather than altering perceived "deficiencies." The article contrasts this model to the model of A.B.A. (Applied Behavior Analysis), which is a reward and punishment system that rewards children for completing certain tasks or modeling certain behaviors. While, it seems this system has been embraced by many, it is also something that may stifle the strengths of an individual, in the sense of inhibiting the story-teller in some way. The article states, too, " The essence of Floortime is that a person learns best when self-motivated, when an inner drive sparks the acquisition of skills and knowledge." Perhaps, this kind of learning teaches the child that their own story is valid rather than requiring the child to learn a new story that may be incompatible with their story-teller's reconciliation of information...

If tacit knowledge, instead, receives a message that behavior is "valid" and not "weird" or needing correction, does the story-teller "relax" and engage in the world with less reticence?

The creative--and archetypal--brain

I'm reading more of Sack's commentary on migraine--this time in a blog at the NYTimes, in which he explores the phenomena of migraine aura, or the visual disturbance that often precedes a migraine headache. Both his own experience with aura, and his research of the phenomena, have revealed a fascinatingly uniform and transcendent geometrical patterns. He writes:

Sacks seems to describe a phenomena of the cognitive unconscious, or tacit knowledge, breaking though, almost taking over or hijacking the conscious, or the storyteller. Does this happen in other mental illness--the conscious or storyteller losing its "supremacy" over the conscious?

Check out the migraine-art slide show here.

migraine and beyond ... forms of mental "illness"?

The jagged edge images are quite familiar to me and, yes, I suspect are indeed a function of the cellular organization of the neocortex/story teller. But that's not so much the unconcious breaking through as it is the inner workings of the story teller itself becoming visible. Hmmm ... alright, there is an "unconscious" aspect of the story teller: its rules of operation (of which we are typically unaware).

And that in turn raises some interesting possibilities for thinking about "mental illness." One could have problems in the unconscious, in the story teller, and in the relation between them?

coherence, probability, logic, confabulation, & the storyteller

I've been thinking more about "the storyteller"/conscious and it's characteristics... and whether or not a need for logical coherence (or rationality?) is really one of them. I bring this up because I've been thinking about the concept of confabulation. This was brought up in relationship to Capgras syndrome last class, but I've been thinking about it more as a result of my experiences working with some individuals with brain injuries.

Does the storyteller really care if a "story", or explanation of observations/feelings/beliefs/etc., are "logical" (probable? rational?)? An example... a man who has recently become incontinent during the night. He has never had many "physical" problems and refuses to accept that it is possible for him to be wetting the bed at night. His firm belief is that someone, in the middle of the night, is coming into his room and urinating both on his bed and him to make it look like he's incontinent.

Some other general cases that come to mind are... psychotic delusions--- stories, but are they logical/rational/probable? Obsessive-compulsive beliefs (which may be a problematic example since they are usually defined as irrational beliefs)? Body Dysmorphic Disorder?

At any rate, it was said during class that in essence "we are all confabulators" which I think is a good (useful?) way of thinking about how the brain and specifically the "storyteller"/conscious works.

confabulation as central to thinking about psychotherapy?

Rich soil for the stories created--consciously or unconsciously?

From Sir Thomas Browne's Religio Medici (1642), via Oliver Sacks' Migraine:

Creating Narratives

I have to say that this past class was one of my favorites (perhaps in terms of helping create for me a coherent structure regarding our conversations throughout the semester up until now?). Personally, the idea of the storyteller brought everything home for me, and the ability to look at mental discrepancies as variances in the storytelling ability of the "I-function" just really logical (for lack of a better term).

In the discussion Dr. Grobstein mentioned after class, I raised the question which had been bogging me down: if people made up stories to explain their unconscious actions AFTER the action impulse, how much consciousness was necessarily involved? And in some ways, might what we consider "consciousness" just be, really, our storytelling ability -- our ability to explain our actions?

Additionally, it seems to me that in many ways we think of ourselves as inevitable, as the culmination of some sort of long process of evolution heading toward the perfection that is us, simply because having I-functions deem this necessary. It is easy for us to say that we pick up a glass of water because of an unconscious desire, but it is harder to admit that our essays (or message board postings) all stem simply from unconscious impulses explained by the storyteller. Still, in some ways, it seems to me like the conscious can almost be explained away. (I'm not sure I agree, in fact, with an assertion Dr. Grobstein made after class that there *can* be something new under the sun.) At the same time, having a storytelling ability gives us a storytelling need ... If we have the ability to explain things (rightly or wrongly) with stories, we need to use them, and not only do the stories need to make sense, but, for the most part, they need to function like stories we are familiar with. If we can explain things, we must. If we can explain them coherently, we must explain them coherently. Once things cease to be coherent, they enter the realm of terror.

I think I am excited about our next discussion because it seems to me the storytelling function is only of benefit in that it allows us to coherently share our narrative world with others in very specific and helpful ways. (At this moment, I feel unconvinced that our so-called "consciousness" can do anything more than that.) Still, I also think this ties in to what we discussed very early on -- that perhaps the aspects of "mental illness" that stem from "deviance" from normality are still relevant in some ways. It is not that there is one way to be, but if your schemata prevent you from dialoguing and sharing with other, there probably is something that can be gotten less wrong.

The causal efficacy of consciousness/stories

I'm glad you like the story teller/unconscious story, and agree that it can help us think about interpersonal exchanges and in that respect think more about "mental illness." We'll track that line more next Monday.

But I think there is more to the story than that. Yes, the story teller can provide an explanation for our actions after they occur. But that doesn't make it useful ONLY in explaining ourselves to others. Stories are also significant in motivating future actions; we act differently because of our stories and this may in turn affect our future unconscious actions. And our stories may or may not make sense in terms of our unconscious understandings. When they don't, we feel internal conflicts, and these too may influence our future actions. In short, consciousess/stories are not just "explanations" of things that have happened; they are also significant influences on what happens in the future.

The sordid story teller

The more I have thought about the nature of the storytellerthe more interested I get in the question of consciousness.

During class wepointed out the many ways in which the story teller is simply responding to theunconscious. It would seem that often,the story teller is really just putting rational “lipstick” on the unconscious “pig”.

Which is to say the story teller is making stuff up to helpgive some plausible explanation for what the unconscious is reporting.

I would argue (borrowing liberally and loosely from Buddhistthought) that in fact, MOST of what the story teller does is habitual and reflexive.

We pick up stories from our society, parents andtelevision. We learn certain stories at a very young age andnever question them. We make up other stories to explain away pain and hurt.

These stories do need to be rational in any sense of theword. They do not need to account for all of the evidence. They just have to beuseful on some level.

What’s more, the big foundational stories that we tellourselves give birth to millions of little stories and story snippets. Anybody who has meditated knows this on anintimate level. Its extremely difficultto get the mind to stop telling stories. Sometimes these stories take the shape of elaborate fantasies andfairytales. Sometimes the mind just cranks out disjointed thought afterdisjointed thought.

Is that consciousness?

I would argue, that in some ways the story teller can almostreside at least partially in unconscious mind. Maybe we can think of the storytelleras an iceberg with 90% of the story residing under the surface and only 10%poking out in our awareness.

In meditation, we slow our minds down enough – not to stopthought – which is all but impossible (at least at first) but to becomedis-identified with thought.

We learn to observe the stories that our mind is creating ina moment to moment basis, without getting lost in the stories. This practice is done not to get rid ofstorytelling, but to develop a very different relationship with storytelling. As people learn to not identify or get lostin the stories that they tell themselves, they find more freedom to react to experiences in different ways. They findthat they become more aware of the relationship between their unconscious mind andtheir conscious mind.

Per my previous conversation with Paul /exchange/bbi08/session19#comment-69558

- I am not sure whetherwe need to talk about another function of mind beyond the unconscious, thestory teller and the I-function. But Ido think that it is important to think about the role that the story teller hasin our lives and how we can learn to control our story teller instead of beingcontrolled by our story teller.

expansions of the story teller?

Stories

Here are some links to a talk given in 2007 by Antonio Damasio. It is posted in two parts; the first is 34 minutes and the second 36.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KbacW1HVZVk

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=agxMmhHn5G4&feature=related

Watching these videos really helped me to process some of the things we have been talking about. Damasio talks about the “fast route” to processing information, which he says is emotion and the “slower route,” which he says is reason. This makes sense in the context of emotions, but is somewhat confusing in that we tend to think of ourselves as “thinking” not “emoting” beings first and foremost. This also defies, in my opinion, what the popular mythology surrounding the ways in which we process information is. Damasio purports in the lecture that “we are always in an emotional state,” which in some ways may be obvious, but isn’t something of which I am always personally aware. As in the article we read last week, Damasio asserts that emotion is the frontline and that feelings are our revisionist perceptions of our initial emotion. The only time we experience “neutral states” to borrow Damasio’s wording is when we are unconscious.

Additionally, Damasio says, “Human emotions are largely unlearned programs of automatic actions and cognitive strategies aimed at the management of life.” His notion of “management of life” is this similar to “making new meaning” or something different altogether? If “management of life” is the usefulness of any given story to make meaning in a particular individual it may well be similar to what we have been discussing. Also, the notion that emotions are not learned, rather are innate, softens one’s perception of those who may exhibit behaviors (stemming from feelings which stem from emotions) that are not within the range of what we, culturally, deem to be “normal.” Just as most of us are born with two functioning kidneys, are most of is born with an emotional “toolkit” of sorts which, depending upon a variety of internal and external factors, we use differentially to shape meaning within ourselves and in our interactions with others? Furthermore he details different kinds of emotion, such as “background emotion” (enthusiasm, discouragement…), and “social emotions” (compassion, guilt…).

*Aside: I’m at a coffee shop as I write this and the song “More than a Feeling” (sung by Boston. Am I so old that nobody else knows this song?) just came on. Weird.

The role of tacit knowledge is still somewhat perplexing. Obviously our brains cannot process and make sense of everything in our environments at once; there is simply too much stimulus. However, is tacit knowledge soaking up and storing its own form of “knowledge” of which we are not aware? And, if so, is it not possible that therapy can reshape tacit knowledge through dealing with the “story teller” which mingles with tacit knowledge, and thus, give new meaning to the implicit nature of tacit knowledge and the explicit nature of consciousness? It seems to make sense that the “story teller” explains the emotion to itself, to the world, through feeling. Because the experience of pain, for example, is something felt acutely in a moment, or over a period of time, but when one is not in pain, one cannot “feel” pain, though one can tell a story about what the experience of pain was like.

Damasio and the bipartite brain

Lots of interesting issues here, and is useful to try and connect the bipartite story we're been discussing with Damasio's story. Thanks for starting us along that path ...

I find D's use of "emotion" and "feeling" slightly confusing (yes, we are, in D's vocabulary "emoting" first and foremost and yes, we are "always in an emotional state), but yes, I do think by "emotion" he means our unconscious activities (which, I think, makes those points less hard to understand). I'd emphasize that it is unconscious activities of ALL sorts ("emotional," "cognitive," etc). And I'd argue that it is far from all "largely unlearned." Our unconscious repertoire reflects genetic information but also our own experiences, and even stories we've heard from others (so yes, we are constantly "soaking up and storing .. knowledge of which we're unaware"). "Mangement of life" is, for me, a little sweeping. We "manage" life partly with our unconscious, partly with our conscious/story teller. And so "management of life" includes things we do without thinking about it, even without being aware of it. But it also includes "making new meaning, which is the business of story telling. We can manage without "making new meaning," but that's only part of our lives.

Thinking about consciousness...

I'm reading Oliver Sacks' Migraine and thought the following passage about consciousness and the connection to self and body might fit into our conversation. (These paragraphs come at the end of a passage discussing "scotoma," which literally means darkness or shadow, and which in this context refers to a particularly severe side affect of some migraines that causes the sufferer to believe a part of his or her body no longer exists):

I particularly appreciate Sacks' final observation above--that "our highest functions" are not entities of their own--but are absolutely dependent on their connection and "continuity" to the body; his observations seem to fit well with Prof. Grobstein's model of the "i-function" intricately connected to, but not always intricately involved with, the unconscious. I look forward to discussing more how mental health and mental illness relate to the disconnect or miscommunication between the two parts.

Derived from but not always related to the unconscious

Intriguing connection indeed. Yes, the I-function/story teller is not always well connected to but is always fully derived from the unconscious (and the material/body).

And an interesting subtlety. Scotomas don't in fact typically "fill one with horror." In fact, as with the anognosias, one is typically unaware of the absence of something (as with the blindspots, scotomas that we all have). What disappears disappears, "taking its 'place'" with it. One only notices the absence if something particular calls one's attention to it, ie if there is a mismatch between a story and .... some new information? I remember becoming aware of a migraine hemianopsia because the number stamped on my gym locker seemed wrong ("26" instead of "1026" because of a left hemianopsia). The input from my unconscious, and the resulting primary story was inconsistent with my derived story?

A Metaphor?

Still trying to locate a place for therapy in the bipartite brain, perhaps a place for a therapist too. So I am offering another horse and rider metaphor, where the horse is the unconscious and the rider is the storyteller. The horse has a set of specialized skills, like flying lead changes. It is also able to perform multiple tasks simultaneously. Interprets primary sensory information and observations, such as shying at a new sight. In contrast, the rider analyzes the information she receives from the horse and attempts to imagine a better way of moving about in the ring, woods, or world. The rider acts as a “semi-independent agent.” This might mean asking the horse to reconsider their previous reaction to a stimulus, not spooking at it. The story that is created by the rider affects the behavior of both the horse and rider.

Therefore, the trainer’s role is to help the horse and rider pair perform better or get their story less wrong. The most important ambition is to increase meaningful communication between the horse and rider. They must engage in conversation in order to come up with a better story for themselves. The trainer can facilitate this conversation. The trainer’s role can be adopted by the therapist. The therapist can try to increase contact between the unconscious and the storyteller.

mental health as conversation facilitation and its complexities

Your response inspired me

Your response inspired me to attempt to extend the metaphor a little further. It allows for multiple interpretations…

If the role of trainer is restricted to a ground person advising the rider, then any account, by the rider of the horse’s behavior, is privileged. The rider has direct access to the horse. Physical access to the balance, contact, and internal activities of the animal. The trainer, in turn relies on indirect sources of information, observations and second hand accounts. This position is advantageous in the objectivity it confers.

This situation can be interpreted in terms of the patient-therapist storyteller unconscious interactions. The both the patient’s conscious and unconscious can be observed by the therapist. The therapist’s conscious is accessible to the patient, but their unconscious is not. There is an asymmetry in the patient-therapist relation according to this characterization. A certain lack of reciprocity on the part of the therapist? Inevitable? Necessary?

Or the trainer’s responsibilities might include riding the horse. The horse’s performance will be affected by the different rider. The differences between the rider and trainer’s style will give rise to different responses from the horse. Any observation of the horse’s behavior is necessarily subjective because of the influence of the rider. This permits the trainer to communicate directly with horse; teach the horse.

Here the trainer or therapist is assuming the task of the storyteller in relation to the horse as the unconscious. This is the synthesis of a new individual or person? Is it possible? Well, there was the time a person tried to teach me how to talk to my unconscious by engaging it in conversation… This process seems to displace the patient’s storyteller. When the patient's conscious and the unconscious are separated, the storyteller is silenced. So the therapist's unconscious and storyteller are interacting with the patient's unconscious? Or is the therapist's unconscious also silenced?

Seriously stretching the metaphor, have we reached the limit of its usefulness? I think we, or at least I, need another story.

Some thoughts

First, I just want to reflect on what Dr. Grobstein's assertion that humans are not superior to other organisms because of our "storytellers." This is an understanding that has not come naturally to me.

I always assumed that humans were the culmination of some great master plan. I'm not really sure why. Perhaps my brain was inherently programmed to believe this. Or perhaps there was some sort of cultural programming that was responsible (more on this next week?..)

If anyone else shares these beliefs... and would enjoy having them shattered... I would recommend Bill Bryson's A Short History of Nearly Everything. I think a more appropriate title would be "a short history of the discoveries of science." I just finished it a few weeks ago and it definitely gave me a few new stories to mull over.

I wanted to post two quotes... The first, from Bryson himself.

"We are so used to the notion of our own inevitability as life's dominant species that it is hard to grasp that we are here only because of timely extraterrestrial bangs and other random flukes. The one thing we have in common with all other living things is that for nearly four billion years our ancestors have managed to slip through a series of closing doors every time we needed them to."

The second is from Ian Tattersal quoted in Bryson's book...

"One of the hardest ideas for humans to accept is that we are not the culmination of anything. There is nothing inevitable about our being here. It is part of our vanity as humans that we tend to think of evolution as a process that , in effect, was programmed to produce us."

There were a lot of observations in Bryson's book to back up these statements, but I just wanted to get the general message here. The storyteller is not some divine gift or possession of ultimate significance... It's just something we have... Like an elephant has a trunk.

Also.... I just wanted to share a story from last weekend. I think it might give us something to think about as we consider the interaction between the conscious and the unconscious.

I ride the train in and out of Philly each Friday for volunteering. As I was riding home last weekend, I sat down next to a woman who looked friendly enough. It was rush hour so the train car was packed and another person eventually joined us. I was sandwiched in the middle of a three person seat.

As the train ride continued towards Bryn Mawr, the woman next to me began to have seemingly involuntary jerking fits with her limbs. Her arm would twitch randomly and then stop. I noticed it, but didn't give it much thought.

A few stops down the rail, things escalated. Her whole body started to twitch and she started making strange guttural noises. She would have a fit of motion and sound, then calm down, readjust herself, and look out the window. It was a very strange thing to observe... slightly frightening because she sounded so angry. It was as if something in her just wanted to go on a screaming rant, but she was trying to keep her mouth closed. Imagine trying to yell a string of angry obscenities but keeping your mouth closed. That's what it looked like.

By now most most everyone in our train car had noticed. I just kind of sat there, palms sweaty, unsure of whether to ask if she was ok or just pretend I didn't notice and not call any more attention to her. It came to my attention that there was a newsletter or something by my feet with headlines such as "Are you Crippled by Anxiety?" and "New Schizophrenia Breakthroughs!"

Suddenly, at the Ardmore stop, after finishing one of her episodes, she calmly gathered her things and said in a pleasant voice, "This is my stop." My and my seat partner let her by and she left.

I didn't really know what to make of this whole experience at the time, but after a few people have suggested that mental illness might be a disconnect between the conscious and unconscious mind I have tried to think about it in these terms. However, in this situation, it didn't so much seem like a disconnect as it seemed like her unconscious mind was trying to bubble out or escape and her conscious mind was holding it in. I can definitely see how people from ages past might say she was possessed by a demon.

Perhaps mental illness is not only a disconnect between storyteller and tacit knowledge (not that anyone suggested it was) but can also arise from a malfunctioning storyteller or a malfunctioning tacit knowledge. Anyone else who might have interpretations of the experience... I'd love to hear them.

"perhaps mental illness is

"perhaps mental illness is not only a disconnect between storyteller and tacit knowledge (not that anyone suggested it was) but can also arise from a malfunctioning storyteller or a malfunctioning tacit knowledge."

I do think that some (I don't claim to know much about all) metal illnesses stem from miscommunication or no communication between the storyteller and tacit knowledge. I really only have experience with anxiety and depression, so forgive me for always talking about them. With depression, one doesn't always know what's happening or why one feels the way they do, which implies a disconnect between conscious and unconscious. With anxiety, one often feels the physical symptoms before one consciously knows what's going on. This stimulates the storyteller to make up a story as to why one feels that way. I think that this story then magnifies the physical symptoms and just keeps feeding itself.

"it seemed like her unconscious mind was trying to bubble out or escape and her conscious mind was holding it in."

That's an interesting idea about how the conscious mind must control the urges of the unconsious mind or at least try to. But it can't always control the unconscious. In the case of anxiety, if the conscious can't control unconscious, it might lead to a panic attack. Why can't the conscious completely control the unconscious?

Tourette's and the bipartite brain

Very rich set of thoughts .... and story. Yes, indeed, the bipartite brain notion encourages one to think more about both the story teller and tacit knowledge, and the interactions between them.

Sounds like your seatmate has "Tourette's Syndrome," (see Tourette Syndrome Assocation), a very interesting/instructive example of the interaction between the tacit and the story teller . There's a wonderful description of a surgeon who has Tourette's in Oliver Sacks' An Anthropologist on Mars. The surgeon feels overwhelming urges to act/speak (coming from the unconscious) that he can sometimes (with difficulty) can control (using the story teller) and other times not. Significantly, the urges occur in some contexts and not in others (eg, when doing surgery).

What makes Tourette's particularly intriguing is its contrast with other situations in which people exhibit uncontrollable movements but do not experience any related internal urges. The latter is rather simply understandable as outputs generated by the unconscious, with no story teller involvement. Clearly, there is a story teller invovlement in the case of Tourette's, since the urges are part of conscous experience. There is not a "problem" isolated to either the unconscious or the story teller, but rather something going on that involves the interaction between them.

Yep, "just something we have"? Or, maybe, something we have that we can work with, make something new from, because of the interactions?

couple quick thoughts

Bipartite brain: inconsistency, emotion, feeling?

My guess is that one can indeed learn to lessen the story teller's concern for "simplicity, logical consistency, and certainty," that that's what underlies zen buddhism among other meditative traditions. But yes too, I think there is an "unconscious part of the unconscious" that involves some level of commitment to at least simplicity and consistency, and that that is indeed a desireable complement to the unconscious lack of concern for such things. Having both, somewhat out of agreement but not in antagonistic conflict is indeed, I suspect, a sine qua non for "mental health".

The "emotion"/"feeling" thing in relation to the unconscious/conscious is a little tough to get one's head around. Damasio calls what the unconscious does "emotion" and reserves "feeling" for what one is aware of, the conscious states that may (or may not) accompany emotion. I'd call "feeling" in this sense "primary" story, as distinct from the secondary stories, interpretations, we place on feelings.

As per our conversation this afternoon, this gets interesting when one starts to think about people who don't "feel" things. Damasio would say they may still have emotions, and I would agree. The question is how to account for the absence of feeling. One possibility is that the relevant signals aren't sent from the unconscious to the story teller. A second is that the story teller fails to incorporate those signals into conscious experience. A third is that the story teller interprets the signals in ways that produce in consciousness something other than feeling. My guess is that one could find examples of all three possibilities (and probably some others as well).

we are the stories.....

I have been thinking a great deal about the story-teller andour sense of self. My father is asinger-songwriter. He has a line in oneof his songs that has always resonated with me: “We are the stories that we tell.” I’ve alwaysloved that line. Who are we,really? Are we are bodies? Maybe to some extent, but as Paul pointedout, Christopher Reeve, wouldn’t necessarily identify with his body. Are we our brains? Sure, but what does thatmean? We don’t identify with our amygdale.

When it comes down to it, our identity is a collection ofstories, big and small that we tell ourselves. Our identity is also acollection of stories that other people tell about us and about the worldaround us. Those stories help usnavigate the world. They tell us who we are.

This becomes really interesting when we think about how ourstories change over time, how our personal stories relate to family stories andsocietal stories. Its also really interesting to think about how stories thatwe tell look in cases of mental illness.

stories: a cross-cultural perspective?

Assuming your father isn't either American Indian or Nigerian, there's an interesting cross-cultural similarity here. The following is from Thomas Young's The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative ...

If we take that seriously, what does it say about "mental health"?Mental health: thoughts about the adaptive brain

Interesting places we went to Monday night, starting with "me" as "all of me" and "containing multitudes" and ending with .... a new (?) definition of "mental health" as "the freedom/wherewithal to create new meaning"? Which would mean that mental health is not a particular state but rather an ability to engage in a process? And that one might have, at any given time, various amounts of that ability but could always move towards having more of it? And could contribute to others also moving towards having more of it as well?

It will be interesting to look at the recently passed mental health parity legislation to see how much of that perspective is reflected there, and how good that legislation is as a foundation for further improvement in thinking about mental health.

Interesting post-class conversation among several of us on the issue of what "consciousness" (the story teller) is good for. It seems not to make us "superior" to other organisms, and indeed may have disadvantages as well as advantages. Yes, it enhances our ability to get it less wrong in particular contexts, but it create new ways to be wrong as well.

Among the advantages of having a story telling capability seems to be some increased "coherence" in the "community of mind," an associated ability to create meaning and hence to conceive additional alternatives for behavior/being. And among the disadvantages ... the host of mental health problems. That are in essence conflicts between unconscious understandings and aspects of one's conscious story of oneself and one's relation to the world? And should be understood/dealt with not as illnesses/disabilities but rather as opportunities to create new meaning that will to varying degrees impact both on the unconscious and the story? Of both oneself and others? The latter to further develop next meeting.

A few other thoughts that struck me from last Monday that I also want to think more about ....

The internal diversity of the unconscious ("I contain multitudes") is really important in thinking about the brain, more so than I've sometimes recognized in the past.

The Capgras syndrome provides a really nice illustration of the multitudes and its significance (the info the story teller gets is, separately, image information and feeling information; when it gets one but not the other it needs to create an explanation/story for the combination). But it also, as recognized by Richard Powers in the Echo Maker, updates an older problem. Yes, "story" is a function of the brain, and yes it affects behavior. But are we back to saying, at a more sophisticated level, that people are "nothing more" than their brains, that Capgras "results from" interruption of a particular pathway (the one conveying "feeling" info to the story teller)?

I don't think so. What's important is to recognize that the "imposter" explanation that the story teller comes up with is only one of many possible stories the story teller might create to account for the observations (just like a particular hypothesis is only one of many that a scientist could come up with given the observations at any given time). My guess is that interruption of a particular pathway will, in different individuals, lead to different stories, of which the idea of an imposter is only one. To understand why someone has Capgras syndrome would require much more than knowing that a particular brain structure was damaged; one would have to know as well all of the things that make a particular brain indvidually distinctive. And the ways that randomness has been turned into meaning by that particular brain (the "choices" it has made).

Yes, its all brain, but to say its "nothing more than brain" is to miss entirely not only the complexity of the brain but its creative capabilities in making meaning.

less wrong

"getting it differently/moving/evolving"?

Thanks, your post was, for lack of a better word, "useful" in that it helped me visualize those ideas differently. To be abstract for a moment...

I agree that "getting it less wrong" can seem to imply that there is an end-goal, Truth to be reached. I used to think in terms of "getting it more right", to reach an endpoint.

I think that "getting it less wrong" also can imply a linearity in things, even if there is no pre-defined end-point, and inquiry/making up new "stories"/observations/etc. can continue indefinitely, and in the absence of Truth.

I guess visualizing it differently is better, in a way that emphasizes that from any given location there is more than "one way" (?/infinite ways?) to "get it less wrong", and the space for "exploration" is much more multi-dimensional.

Maybe the emphasis should be on change, i.e., to “help keep things moving/evolving”.

multi-dimensional inquiry

less wrong = more useful?

Yeah, there is, for better and for worse, a long "less wrong" history. And no, it shouldn't be understood as implying there is a "right." Neither in the sense that there is a fixed long term objective nor even in the sense that at any given time, there is a single alternative that is better than all other alternatives. The basic idea the phrase is intended to convey is that we are always exploring from the present, needing to find ways to deal with present problems, that we can choose not to go in directions that have known problems and instead to conceive/try other directions, but that leaves still an infinite number of possible directions to explore.

"less wrong" means "notice and fix some local problem" with a new solution, one that hasn't been tried before (as, in the context of science, account for a new observation that one couldn't account for with existing stories in ways that create new challenges). "more useful" could well be understood to mean the same thing, but would, I suspect, equally call to mind some things that one doesn't intend by it.

Are there ways to use words that don't do that? The answer, in general, is probably no. But that doesn't mean one shouldn't try to get it less wrong, more useful in particular cases/local circumstances. Thanks. Let's keep working on it in this particular case.

Post new comment