Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Mental Health: Interacting Brains

|

Mental Health and the Brain:

|

|

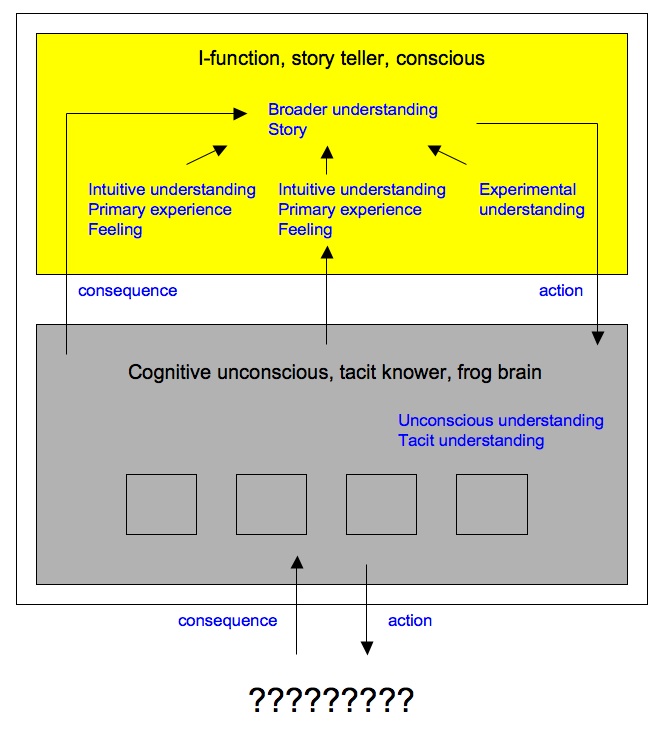

Our fifth session and resulting on-line forum discussion focused on two "loops" by which the brain learns/adapts/changes. One, largely unconscious, involves a number of parallel comparisons between expectations and the results of action and yields a wide array of unconscious understandings of both of both the world and one's relation to it The other involves a comparison of conscious experiences and understandings ("stories") with unconscious ones. The latter provides an interesting framework for thinking about "mental states," including those characterized as "mental illness," and suggests a possible locus for psychotherapy. The perspective also calls attention to the need to account for interactions between brains, in connection not only with psychotherapy but also social and cultural influences. That's the topic for this coming week.

Readings for this week

- Social cognition and the bipartite brain

- Exploring disability: images and thoughts (post brief reactions in the individual image forums)

Relevant new things elsewhere

Thomas L. Friedman, OpEd, New York Times, 12 October 2008 ...

"Mother Nature is just chemistry, biology, and physics .... you cannot spin Mother Nature. You cannot bribe Mother Nature. You cannot sweet talk her, and you cannot ignore her ... And Mother Nature always bats last, and she always bats a thousand."

Friedman suggests "There is a parallel with markets." And, perhaps there is some parallel with the brain and culture as well? Because most of our experience is in dealing with other human beings, perhaps we overestimate the potency of bribery, sweet talk, logic, and well-meaningness? How potent are virtue, reasonableness, and the like in dealing with the brain? with culture? Why do they work to the extent they do, and can we make sense of their limits?

Reaching an autistic teenager, NY Times Magazine, 19 October 2008

"Perhaps, this kind of learning teaches the child that their own story is valid rather than requiring the child to learn a new story that may be incompatible with their story-teller's reconciliation of information ... If tacit knowledge, instead, receives a message that behavior is "valid" and not "weird" or needing correction, does the story-teller "relax" and engage in the world with less reticence?" ... Sophie FWhere we've been ...

Sacks seems to describe a phenomena of the cognitive unconscious, or tacit knowledge, breaking though, almost taking over or hijacking the conscious, or the storyteller. Does this happen in other mental illness--the conscious or storyteller losing its "supremacy" over the [un]conscious? ... mstokes

Perhaps mental illness is not only a disconnect between storyteller and tacit knowledge (not that anyone suggested it was) but can also arise from a malfunctioning storyteller or a malfunctioning tacit knowledge ... ryan g

I've been thinking more about "the storyteller"/conscious and it's characteristics... and whether or not a need for logical coherence (or rationality?) is really one of them. I bring this up because I've been thinking about the concept of confabulation ... it was said during class that in essence "we are all confabulators" which I think is a good (useful?) way of thinking about how the brain and specifically the "storyteller"/conscious works ... LauraC

it seems to me like the conscious can almost be explained away. (I'm not sure I agree, in fact, with an assertion Dr. Grobstein made after class that there *can* be something new under the sun.) .... it seems to me the storytelling function is only of benefit in that it allows us to coherently share our narrative world with others .... ysilverman

I do think that it is important to think about the role that the story teller has in our lives and how we can learn to control our story teller instead of being controlled by our story teller ... adiflesher

is tacit knowledge soaking up and storing its own form of “knowledge” of which we are not aware? And, if so, is it not possible that therapy can reshape tacit knowledge through dealing with the “story teller” which mingles with tacit knowledge, and thus, give new meaning to the implicit nature of tacit knowledge and the explicit nature of consciousness? ... Sophie F

I am offering another horse and rider metaphor, where the horse is the unconscious and the rider is the storyteller. The horse has a set of specialized skills, like flying lead changes. It is also able to perform multiple tasks simultaneously. Interprets primary sensory information and observations, such as shying at a new sight. In contrast, the rider analyzes the information she receives from the horse and attempts to imagine a better way of moving about in the ring, woods, or world. The rider acts as a “semi-independent agent.” This might mean asking the horse to reconsider their previous reaction to a stimulus, not spooking at it. The story that is created by the rider affects the behavior of both the horse and rider ... the trainer’s role is to help the horse and rider pair perform better or get their story less wrong. The most important ambition is to increase meaningful communication between the horse and rider ... The trainer’s role can be adopted by the therapist. The therapist can try to increase contact between the unconscious and the storyteller ... jrlewis

The advantages and problems of two loops

Empirical knowlege and getting it less wrong in distributed systems

The local maximum problem and coherence

Conflict and conflict resolution

Finding new directions: the story teller as creator

|

My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will ... William James, 1870 A world that can be painted darker can aso be painted brighter ... Serendip The capacity to to tell new stories, to create meaning is robust/resilient .... |

Problems: unresolved internal conflict

Adding a third loop: additional advantages and problems ....

- Multiple paths of exchange

- Advantages: creating new things that one couldn't have created alone

- Problems: unresolved conflicts, inhibition rather than enhancement of individual story creation

- Culture without stories

- Culture as stories, revisable

Brain re mental health summary to this point ...

- Observations to date are consistent with the mind being in the brain, and hence with the mind being material

- Observations to date are consistent with the brain having unconscious and story telling functions (all internal experiences), with the latter deriving from and acting through the former

- Observations to date are consistent with unconscious understandings being rooted in an ongoing exchange with the outside world, and story telling understandings being rooted in an exchange between the the story teller and the multiple elements of the unconscious

- Observations to date are consistent with recognizing conflicts in understandings as an important feature of human life, one that can create both problems and opportunities

- Manipulations of matter can affect both the unconscious and internal experiences and so behavior

- Stories reflect organizations of matter and so can also affect both the unconscious and internal experiences as well as behavior

- "Mental health" issues emphasize the important role of stories and conflicts (both within and between people) in human life

- "Mental illness" can be understood as breakdowns in ability to make use of conflict to create new stories and new meanings?

- The task of mental health workers is to enhance peoples' ability to make productive use of conflicts within themselves, as well as between themselves and other people and other aspects of the outside world? To create new stories/meanings that in turn open new possibilities?

Trying it out .... (see links for background and discussion of each case)

- Following a car accident, a man experiences uncontrollable bouts of depression ... Exploring Disability ... discussion

- Following a care accident, a man accuses his sister, who has been taking care of him, of being an imposter. ... The Echo Maker ... discussion

- A man who hears voices in his head and has successfully hidden that from everyone close to him becomes enraged when he discovers that his father had also heard voices all his life and had never told him about it ... Muses, Madmen, and Prophets ... discussion

- A resident in a rehabilition hospital urinates in bed every night, and insists there is an unknown nightly visitor who is responsible ... LauraC ... discussion

- A woman on a train has what seem to be involuntary jerking fits and makes strange guttural noises. She seems to be very angry, and having trouble controlling herself ... ryan g

- A young girl is terrified of a mysterious person who finds her in bed at night and lies on her, preventing her from moving ... ... Sleep paralysis ... discussion

- A woman becomes preoccupied by someone repeatedly writing "I love Sarvis" on the stall divider of the girls' bathroom in the school where she works . Sarvis is her nine year old son. .... The tiny hand that rocks the cradle ... discussion

Moving on to more specifics ...

Comments

Sorry I have missed posting

Sorry I have missed posting the last couple of weeks...

I BRIEFLY looked at the other posts this week as I am trying Paul's suggestion to post thoughts, etc. without reading others and then going back, so please excuse if I repeat.

During the week, I have been thinking about the different case scenarios we were given in last weeks class and a question Paul asked about why (specifically, I believe to my group answer) we automatically immediately respond with the biological or medical aspect. During the week I was studying and began to feel a burning sensation in my stomach and then a headache came. I know for myself that my BODY SENSATIONS (burning in stomach, headache) are more noticeable and familiar and much more accesible than feelings of...anger, frustration, sadness. And that the physical cna give me (though can be quite detached at times) important clues to figure what is going on within my internal self. Because I am more familiar and comfortable with stating, "I have a headache," than, "I feel angry because..." does not mean that one is more important than the other and that the headache is caused by a some biological or medical disaster.

That being said, I wonder for those who have a tendency to immediately go towards the medical or biologically how connected/detached do they feel to their body/mind?

I have no idea if this is making sense as I am rambling my thoughts down quite quickly!

See you tonight.

Individual Relationships

It always takes me so long to get my feelings all sorted out. I wanted to comment on Sophie’s “ramblings” post. I do not necessarily agree that culturally we are defined based on “self, the individual rather than relationships to other people”. The reason I say this is that so much of our behavior is socially constructed and such a great percentage of those social constructs are created to control/survive social situations. I feel as though people are less likely to create stories in which“I” is the protagonist. From the outside people are also judged based on their relationships, whether those relationships involve their boyfriend, husband, family, friends or lack of, all are social constructs. Maybe I am missing the point but I feel as though people are most often times not the protagonist in their stories. I believe that at least in the present day people have begun to place such a large importance on their relationships with others that they may be loosing the relationship with themselves.

For example, in Greece it is extremely important (if you are a woman) what the women in your neighborhood think of you. When I was younger my grandmother would always yell at me not to climb trees, to wear dresses and not to raise my voice. After any complaint she would always mumble what is the neighborhood going to think… I believe that she was no longer the protagonist of her stories, but simply a character in everyone else’s. I believe this could have been damaging to her relationship with herself. This is one of many examples that I feel show that we are victims of over-socialization to the point that we can no longer understand or rationalize with ourselves.

Perhaps this is why so many people today require a psychologist as part of their entourage, because it has become increasingly difficult to understand the relationship they have with themselves, if they base their lives on the relationships that they have with others.

I think that this is imperative when considering “mental health”, because the concept of “mental health” is not really a social one, but instead a very individual concept. However, as society develops and as social norms change people are becoming more and more the characters in others stories and not developing stories in which they are the main character. People are identified and defined with respect to their relationships with others.

Now I feel like I am rambling and I am not even sure whether or not there is any validity to what I am saying, but I would like to explore what others think, “does culture [really] define people based upon ‘self’, the individual rather than relationships with other people?” Does it really make a difference?

Worrying about what other

Worrying about what other people think of us, while superficially relational is rooted in “I” and a “self” as defined by culture, which may be in conflict with one’s own stories. When I was in west Africa, there was not a sense of “what do people think of ME?” But “self” or "me" IS community, which is vastly different from the entanglements to which Lisa refers, in which culture attempts to homogenize individuals, which may, too, create internal and external conflicts.

My point was not that we are the protagonists in our stories; rather that individual "merit" and achievement and "survival of the fittest" mentality is a cultural construct that undermines our tendencies to be relational and outward looking.

For me, mental health is inherently relational because tacit knowledge is the deep well of history, experience, family, friends and culture that we store… and only later spills into our story-telling; these are the things of which we are not "aware" of which "I" is not aware. That is not to say individual thoughts, feelings, fears, anxieties are invalid, but that the “self” exists only in relation to others, not in a vacuum. Much internal conflict comes from not knowing one's role in relation to others, in relation to a social schema that validates certain behaviors and invalidates other behaviors...

Sorry for the jumble. I'm not really sure what I'm talking about, clearly!

Someone once suggested to

Someone once suggested to me that a potential therapist is a person who is interested in and talented at mucking around in others tacit knowledge or unconscious. This person would make observations about their patient’s unconscious’ activities, a task the patient is incapable of performing themselves. Then, the therapist should use these understandings to facilitate storytelling activity in their patient.

The therapist would also have to communicate with the person’s consciousness or I-function. The choice and execution of interacting with a patient or their brain on both levels is interesting. Strikes me as a bit of a juggling act for the therapist. Yet juggling, once achieved, is an unconscious activity. So did I just incorporate the therapist’s unconscious in the interaction? This description superficially fits with our discussion of the interpersonal loop in class.

more ramblings

I disagree wholeheartedly that our culture is not one that defines us based upon the individual rather than her relationships to others. I maintain that we are taught not to think of ourselves in the context of our friends, families and our broader human family, but rather as individuals struggling to find our way and only secondarily as social creatures. I agree that a conflict occurs because we are inherently social and this cultural message to which I previously alluded is incompatible with our “natural” tendencies towards relatedness. Katie wrote, “constantly striving consciously to define ourselves in such a way” from where does that “striving” come from if we can agree that it is in conflict with our “natural” tendencies? I was not arguing for a cultural conflict, rather an implicit cultural message that when stored in tacit knowledge is, in fact, conflicting with a tendency towards explanations/stories that are relative in nature.

Martin Buber, (Martin Buber) a philosopher describes two fundamental relationships, I-it and I-thou. Setting aside, for the sake of clarity, his third relationship that of I and God (God as the ultimate “thou”), Buber’s point is that I-it is an experience of a thing as we analyze it, understand it and scrutinize it as something apart from us. In this case, we experience the world as something to know and understand. Whereas I-thou is relational, an "encounter" in Buber's language, which entails a recognition of a relationship between two people in which neither is the “same” afterwards. The distinction here is an important one, I think, in that we can relate to others as objects, which results in alienation or relate to others as dynamic beings, with their own internal experiences, recognizing and reflecting back to each other the limitations of our “knowledge” of ourselves and of one another. We are alienated from ourselves, in conflict with ourselves, precisely because we are alienated from other people.

Buber wrote: "The world is not comprehensible, but it is embraceable: through the embracing of one of its beings."

And: "All actual life is encounter."

Finally,: "Persons appear by entering into relation to other persons."

While the "me" of whom I am aware can never be the same as the "me" other people perceive, I can only exist in relation to that which I perceive and those who perceive me. There can be no conclusive "knowing" of anything or anyone, making conflict, internal and otherwise, "inevitable." It is only, perhaps, with the acceptance of such limitations that conflict can be eased, valuing rather than devaluing our shared lack of "knowing." Perhaps, though different, our stories are in some ways overlapping and, yes, interchangeable. Maybe this entails letting go of the sanctity of "self" and falling (easing?) into the uncertainty of connectedness, of narrative.

Sleepwalkers

During the weekend I read three different articles about sleepwalking and all these articles reported a Finnish study of 1997. The study suggests that sleepwalking is more frequent in children than in adults (6.9% female children and 5.7% male children are sleepwalker while only 3.1% adult women and 3.9% adult men are sleepwalkers). The only explanation that was given is that this phenomenon generally occurs during slow wave sleep SWS and children and young adults spend 80% of the night in SWS. Therefore, the phenomenon decreases as a person ages. But, could sleepwalking in children be also related to the fact that their I function or perhaps other areas of the brain are not completely developed?

zombies

I feel like I may have used up my...

Atlantic quotient for the week, but I am quoting it anyway, as I've found an article that felt just as apropos to our discussion, if not more so.

In "First Person Plural" Paul Bloom argues, much like we have done in class, that, in each of us, there exists a multiplicty of selves responding to different stimuli (and, of course, occasionally clashing -- causing problems like addiction, overeating, etc.). And, like Katie above, he also brings up the point that the way we see other people and the way we see our"selves" is very different. In fact, he argues, we see other people's choices as somehow being inherent to their nature, whereas our own are dependent in cirsumstance. Where exactly does the self lie? And does rationality dominate? And would it be better if it did? And, of course, in the end, what are we gunning for?

I think part of the problems lies in our definition of what exactly the self/(selves) is/(are) -- and in terms of what its needs and wants are. In a way, I think the thing about our social relationships in the world is that we look to them to confirm the stories our I-function is telling us about ourselves (or about the cohesion between selves that is being created). If friends' narratives about us don't correlate with our own narrative -- we are more likely to change friends than narratives.

In many ways, this conscious usage of the world makes sense to me -- the part of us that creates narratives engages in the world in a way that confirms those narratives. That is why people find even innocuous lying/story-telling kind of annoying, and why confronting other people's "psychoses" make people so uncomfortable. While I agree with Sophie that our conflicting selves can help us -- do help us, in the end, because no one self alone has all of "our" best interests at heart -- the I-function revels in this internal conflict less. And I agree with Katie -- our relationships with others are really useful to us in that they define ourselves, and their relationships to others (or to us) are useful to us only in how that, too, helps us define ourself.

We are all narcissists (to a literal degree, if not a diagnostic one).

More on the relating self...

More generally, I think that the term "self" when we apply it to other people is a completely different concept from the term "self" we must use to define ourselves. My definition of myself is not something separate from me but a constantly updated set of conscious and tacit knowledge and “memories” that exist inseparably from my body/mind. How I define other people and conceptualize their "selves" is secondary however, because I can never know/experience how they actually relate to the world, but rather can only understand how they relate to the world through the lens of my own relationship to the world. Trying to conceive of ourselves in the same way we conceive of others - similarly to what I was saying above - could also provide conflict, because conclusively it is an impossible goal!

self as individual or relation: internal conflicts?

Could of course be both, from without and from within. But I think the former is more thought about, so glad to see you call attention to the latter. If there really are "social" boxes in the unconscious, then the story teller could well be faced with conflicts in trying to create a coherent story from unconscious inputs that, on the one hand, emphasize the value of relatedness and, on the other, report that relatedness causes problems in other realms.

self defined by community

Sophie raises an interesting question in her "Rambling" post above: "that our culture tends to define people based upon “self,” the individual, rather than relationships to other people. It seems that for people who may define themselves, or create stories in which “I” is, perhaps, not the primary worldly relationship, but rather “other” is (or community), this creates internal conflict."

It seems that many world cultures would define the individual much more in terms of relationship to community than in terms of individual or "self" properties. In such communities, does conflict with the community then drive more internal conflict--and as a result create more of a distinctive sense of self within the person--or does the conflict continue to perpetuate itself externally between the individual and the community, with the individual never fully "internalizing" the conflict? How would such a conflict be properly mediated in such a culture? Finally, it would be interesting to know (are there studies which investigate this?) what the incidence of mental illness, or conflicts such as we're considering, is in cultures which focus more on community rather than individual. Is there increased pressure for conformity and non-conflict within the community, perhaps creating more conflict in the self, or does the lack of focus on the individual or self actually create more "space" for the self, which in turn might diminish internal (and by extension, perhaps, external) conflict?

"I-function," "story teller," culture, and conflict

Yep, and this indeed raises some interesting questions (here, and above and below). Along these lines there is a perhaps relevant story about the story we're developing. The "I-function" is an idiosyncratic neologism I developed for teaching purposes that was challenged by a student five or six years ago precisely on the grounds that it was not culturally universal. Partly for that reason, partly for others, I started using the term "story teller" instead of "I-function." And then had to wrestle with the question of what the relation is between the "I-function" and the "story teller". For some of this history of this, see The Art Historian and the Neurobiologist.

My current thinking is that the "I-function" is a subset of the "story teller," and it may indeed be different in different cultures, and in different people in the same culture. In particular one's story of oneself may be either primarily relational ("I am defined by my relations to other people") or primarily individualistic ("I exist and I have relationships with other people"). At the same time, there is a "primal" characteristic of the "I-function": it is what one most directly experiences ("primary story") and what cannot be challenged by others. Someone may challenge one's story of why one is in pain, but cannot, in these terms, challenge that pain is being experienced. The only one who can know how one feels at any given time is oneself (though others may see signs of relevant unconscious activities that one is not oneself aware of).

Yep, I think there is more than adequate grounds for conflict in all of this, both within people and between people and other people (up to and including culture). My guess is that one will find evidence of conflict both in individualistic and in community oriented cultures, but that expressions of that conflict will be different. As will the new stories that emerge from the various conflicts.

back to earth

thank you

I had actually been meaning to write up a longer version of my dad's story in the forum and time had not permitted it.

Ppart of the point in my telling my dad's story is that helps to approach the Brain holistically - much as it helps to approach the Body holistically.

My father works with schizophrenics. His therapy for them is based on a combination of summer camp style socialization and therapy for brain injured patients. In his brochure he likens his program to physical therapy for the brain.

In all of our cases we should remember the brain's capacity to re-wire itself.

We all know that the body is very responsive to exercise and yoga. We have been learning more about the brain's ability to respond to certain types of exercise as well.

mind/body, story/unconscious, abstractions/practical answers

"Everyone of our suggested treatments ... is no different from what would happen ... under the current mental health programme"

Stories in the Service of

Stories in the Service of Making a Better Doctor This interesting article appeared in the NY Times 10/23/08

Given our discussion last week, I think the article is pertinent. It talks about the inclusion of "narrative medicine training" for medical residents as part of their training. One of the physicians who advocates for this sort of program said, "As we improve the technology of medicine, we also need to remember the patient's story." Perhaps, reshaping medical education to include the entirety of the patient, not just her pathology, but her story, too, will also affect the perception of the "story" and make it an expected component of medical treatment and mental health evaluations and treatment. I'm not a proponent of the use of the medical model as the best or the only treatment for mental health, but I think the more individual stories can be heard, in a variety of contexts, the more "health" becomes a possiblity for a broader range of people.

The importance of stories in medicine

Thanks for this article, Sophie. Oliver Sacks shapes his discussion and investigation of migraine around hundreds of his collected stories of neurology patients he saw and treated over the years; he quickly discovered in his practice of medicine that he would never successfully help or treat his patients without hearing and understanding their stories. (I know I keep mentioning Oliver Sacks and his book Migraine, but as I continue reading and thinking about it, I continue to find great parallels to our discussion.)

Perhaps the idea of story-collecting has always been more central to the practice of neurology than other fields of medicine (I remember that on my first visit to a neurologist when I was 10 the doctor collected both my life story and my mother's life story), because neurology deals more with the intersection of our story life and our medical self; but it seems very reasonable that the intersection would extend to other areas of medicine, as indeed our story life and medical self never fail to intersect.

I thought the discussion of

I thought the discussion of the meaning of dreams/why we dream was really interesting and I hope we discuss this more. If dreams are a way of handling our anxiety it seems that this is just another type of story we tell ourselves.

After our discussion on Monday I was reading “Love’s Executioner” by Irvin Yalom, which is the book I am reading for my book review and was really fascinated by his views on anxiety. He says that anxiety arises when we try to cope with the four “givens” of existence which are the inevitability of death for each of us and those we love; the freedom to make our lives as we will; our ultimate aloneness; and the absence of any obvious meaning or sense to life.

I haven’t finished the book yet and I don’t know if I agree with his theory about basic anxiety completely, but right now I think it makes a lot of sense. It is really sad to think that much of our worldview and even in our sleep we spend so much time trying to control our overwhelming fear of just being alive.

death, freedom, aloneness, and meaninglessness?

Ramblings

I like the idea that internal conflict can be a “good” thing if it can be used as a catalyst for change. I like it in that it is empowering and a way of thinking that does not place blame or judge people for feeling ill at ease, depressed, anxious, etc. It sort of reminded me of the images we looked at last week created by David Feingold. He wrote of this image /exchange/feingold08/hiddendisabilities, “Which is more problematic: When your hidden disabilities are hidden from those around you or when they're hidden from yourself?” I think this is a really interesting way to look at this issue and a question that has no answer, since both sound undesirable. I recall, at the beginning of the course, discussing “intervention” and when it might be (if at all) appropriate to interject oneself into someone else’s world in order to “help” them. Perhaps, we, collectively, need to work on evaluating other peoples’ signals better… How able are we to, whether through the story-teller function or processing through tacit knowledge, able to “sense” or give meaning to other peoples’ behavior in terms of body language and that which is not explicitly stated? Is intuition something with which one can become more in touch? This, too, harkens back to what Adi said in class about being sensitive to when other people just want someone to listen to their story and not attempt to shape it or evaluate it in any way.

Something I find interesting, too, is that our culture tends to define people based upon “self,” the individual, rather than relationships to other people. It seems that for people who may define themselves, or create stories in which “I” is, perhaps, not the primary worldly relationship, but rather “other” is (or community), this creates internal conflict. How do continually evolving relationships with others affect our relationship to ourselves? How might people who have a different sense of their relationship to the world, in a sense, be further alienated from themselves and others as a result? How can we make room for meaning to be created and accepted more widely?

In one of his descriptions of his work, David Feingold also poses the question, “what would the world be like without quirky people?” Is there a way to maximize individual potential without overtures akin to homogenization?

Is the story teller looking to tell stories that create consistent meanings over time? It would seem to make sense and if that is the case, how do we "step outsid of ourselves" and know, if it can be "known" that there are alternative stories?

the route to mental health?

"How do we "step outside of ourselves" and know, if it can be "known" that there are alternative stories?"

Initial thoughts...

I wanted to bring up this idea of the "100th monkey phenomenon" again... Has anyone heard of it? I mentioned it in a post a few weeks ago, but I think it's more relevant to the discussion at hand. The idea is that two populations of monkeys are separated by a geographic structure like a lake where they can have no direct contact for communication or observation. When a critical number (hence the name...) of monkeys learn a skill on one side of the lake (e.g. how to open a banana more effectively), the knowledge seems to jump to the other side of the the lake and those monkeys somehow know how to open the bananas in the more effective way.

Like I said before, I'm pretty sure this is not a hard and fast scientific theory. I actually read about it in a book that was encouraging increased awareness of the damage of nuclear stockpiling. The idea seemed to be "If we can just get enough people to be aware of the dangers of nuclear weapons, it will eventually make the jump to the collective consciousness."

Anyway... my point now is that if there is something somewhat like this, it might be a good example for communication between the tacit knowledge of two different people. We seemed to be a little fuzzy when we were coming up with examples for that gray arrow. Anyone have any thoughts? Too much of a stretch?

Another thing on my mind is the compartmentalization of the bipartite brain. I feel like I need more clarity as to what processes are a result of firing in the I-Function and what processes are a result of firing in the the Tacit Knowledge. Right now, I feel like the boundaries are pretty loose. An example would be memory. I would have intuitively put that into the Tacit Knowledge, but in class we talked about it as part of the I-Function. Is there a working definition of the two compartments that we could use to more concretely assess upcoming mental health/illness?

Finally, I know that people are beginning to find anatomical correlations. For example, the I-Function is in the neo cortex, the tacit knowledge may be located in lower brain areas, and language is in Broca and Wernike's. Can anatomical discoveries shine any light on the structure/sectioning of our model?

I'm looking forward to exploring these specifics and more with our bipartite story in the upcoming weeks...

"two compartments"

'Is there a working definition .... ?"

Actually, probably not, except insofar as we are creating one as we go along (see comment below). But yes, there do seem to be at least some anatomical correlates. And there is a relevant story about "memory." There is a relatively clear operational and empirical distinction between "declarative" or "explicit" and "procedural" or "implicit"memory. The latter corresponds roughly to information in the unconscious, the former to story information. People with Alzheimer's, for example, may act in ways that reflect prior experiences but have no awareness of having had such experiences. For an interesting clinical exploration of this, see dementia and the unconscious.

100th monkey and the quality of stories

It's interesting; I had also heard of the 100th monkey in someinspirational setting and was somewhat skeptical about the story. Itturns out that the story has been subject to some serious questions.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hundredth_Monkey

I think what it shows us about the communication between two unconsciousnessis that we as humans actually have a tremendous reliance on stories and that astory does not have to be "True" or "Scientific" to havetremendous meaning for us.

Often we seem more tuned in with the body language of the storyteller or other things that guide our unconscious to trust or not trust, likeor not like, feel attracted to or repulsed by the story teller.

Often we do not make a choice about a story based on how muchsense it makes but based on how much we trust and like the story teller. Of course our stories shape our unconscious aswell and prime it to react to certain stories and certain story tellers incertain ways.

100 monkeys, or humans

What's to be skeptical about? Do you both know the story of the birds in England that quickly acquired the capacity to pop the little papers sealers out of milk bottles? Yes, lots of animals, including ourselves, learn by unconscious copying or mimicking, and so new understandings can sweep rapidly through a population. See Malcom Gladwell's Tipping Point.

And yes, there's a down side to this as well. We are indeed influenced by "body language ... or other things that guide our unconscious to trust or not trust, like or not like ..." (see Malcom Gladwell's Blink). All of which is to say it pays us to be aware of BOTH unconscious and story communication.

medical therapy

"medical"?

...

Observations to date are also consistent with the mind not being in the brain but needing a properly disposed material brain to express its powers.

The brain and mind do seem to have both conscious and unconscious functions and many stories or internal experiences are derived from the unconsciously supplied material. Aristotle is famous for saying that there is nothing in the intellect(consciousness) that is not first in the senses (unconsciousness). But, that does not mean that the intellect and its powers are material it just means that in order to express those powers, properly disposed matter is required.

I think that the story contained in Grobstein’s summary above is going to be helpful in treating many mental health problems but Idon’t know if it is the “least wrong” one yet.

I agree that it is the job of the mental health professional to help the patient to examine their “story so far” that explains the relevant perceptions of reality that the patient has. And then take that examination and determine if a better or more Realistic story might work better for them. To ignore conflicts between my perception of reality and the effects that my actions, (that were based on myperceptions) have on me would no doubt cause mental illness. So, to acknowledge the conflicts and seek to resolve them can help.

This business of creating meaning still confuses me. Does it mean we are trying to figure out a better way of convincing ourselves we should bother to keep living at all? Since we are skeptical of any religious notion of why we live do we need to create a meaning of life in order to keep going? Is that what is being suggested?

"more Realistic" or ... ?

Yep. And the differences between the two stories seems to hinge on whether a "a better or more Realistic story might work better for them". And perhaps particularly on whether "more Realistic" is the same as "better." Which, of course, raises some interesting problems about how we decide what is "more Realistic." Besides, maybe "more Realistic" is sometimes less important?

Making meaning

I wanted to try to give my take on creating meaning.

I think this phrase can sound very scary topeople. If we are creating meaning, does that mean that there is NO REALMEANING. If so, is the world inherently a dark place and are we all going to suddenly start wearing,berets, black turtlenecks, smoking unfiltered cigarettes and contemplatingsuicide.

I actually find the idea of "making" meaningto be very hopeful and creative.

Let's take a hypothetical example that mayhave happened two weeks ago.

Me and my girlfriend are out for a walk withour cats. Yes cats. We encounter a tree. Does the tree have meaning?

I would argue that all four of us mademeaning out of that tree.

Bamba theless adventurous cat probably made the following meaning: Scared! Scared!Scared! What's that noise? What's that big thing over there making that barkingnosie? What's this big thing in front ofme, maybe I can hide behind it.

Bisli themore adventurous cat probably had similar thoughts, but also realized that thebig thing might be a good thing to try climbing.

My girlfriend and I, in the mean time werelooking at each other, being vaguely embaressed to be hanging out with twoterrified kittens, in harnesses and leashes in the middle of a public park inPhiladelphia.

Had we been less pre-occupied by our scaredcats, we might had any of the following thoughts in relation to the tree. Wow its really pretty! I wonder who plantedit? I wonder how old it is? Boy am I thankful for the shade. I lovephotosynthesis! I wonder why the trees here turn color slower than the treesout in the burbs? I think the branches look like neurons and I would like totake a picture of it.

So what does a tree mean?

The answer is that we are constantly makingmeaning out of trees and everything else.

A tree means fuel, beauty, food, oxygen, aplace to nest, a thing to climb, wood for a house or paper, green space, aplace to play and so many other things. But it only means those things inrelationship to the minds that interact with it.

When we make meaning of the tree - we arealso free to discover brand new possibilities. We can create brand newmeanings.

I was struck by an articlein today's New York Times aboutentrupenuriship and new ideas. The business people cited here talk about serendipityand the need to keep and open and curious mind in relation to the world.

It seems to me that they are talking aboutbeing open to new stories. About makingmeaning.

Ido agree with Martin's statement, that without meaning people have a reallyhard time. If they don't have bigger stories to help make sense of their livesthey really do end up struggling, despairing or losing hope. Sometimes those stories are offered byReligion, or society. But even so a person actively has to make meaning ofthose stories. Religion still requires us to constantly make meaning ofthings.

Viktor Frankel, a psychologist who survivedNazi concentration camps wrote about this. He said that the difference betweenthose who survived and those who died was the ability to find meaning in whatwas going on around them.

Frankel told the story of who had lost hiswife of many years. He was terribly depressed and had seen several therapists. He came to Frankel and explained thesituation. Frankel asked the man if hethought that his wife loved him. The man replied, yes she had very much. Frankel asked the man if in outliving her, hehad spared her the grief of having to deal with his death. The man thanked him for helping to makemeaning out of his suffering.

meaning making via story conflict

I think I understand what

Perception

I guess that perception is a good word as well to describe this process, but I think its important to realize that we are part of the world and our perception is constantly interacting with and being shaped by the world - but also interacting with and shaping the world.

In that sense, it seems to me important that we learn and teach the ability for people to be active in their making meaning.

Brains, interacting and otherwise - PG thoughts

Strong sense of some of the benefits of interacting brains in our last session, both in general and in highlighting differences in ways of thinking/stories. Is the brain/mind material, like the kidney? Sure. Ought one therefore to approach the brain the same way one does the kidney? No, because story telling and story revising is an intrinsic part of the function of the brain, and is not of the kidney. Manipulations of the brain inevitably and necessarily affect one's stories whether that is intended as not, as per Adi's account of the sequelae of surgery for a brain tumor. Manipulations of the kidney may, of course, as well, but the link is less direct. The upshot is that a "medical model" that neglects the significance of story telling is clearly inappropriate for thinking about "mental" health (and may be, as well, in many cases of "physical" health).

None of this says that one shouldn't, as appropriate, make use of therapeutic procedures developed by a "medical model" approach. What it does suggest is that one shouldn't presume that such procedures will be effective in all situations. Perhaps even more importantly, one shouldn't presume that the medical model approach to research will in the long run uncover effective procedures for all situations. If story telling is a central feature of brain function, that needs to become a consideration in research aimed at developing effective mental health therapeutic procedures.

And one needs, as well, to incorporate the idea that "conflict" is not itself a problem but instead a driver of ongoing change, of "getting it less wrong." What is problematic ("unhealthy"?) is unresolveable ("destructive," "unconstructive"?) conflict, conflict that inhibits the generation of new candidate stories? That seems to me worth thinking more about, in terms of the brain as well as in terms of interacting brains.

Looking forward to seeing how this new brain-based story of mental health, one featuring dynamic interactions between the unconscious (with "filters," "schemas") and story telling, evolves (or fails to) as we move into encounters with an array of more concrete issues/phenomena.

Interaction and the story teller

One of the (many) questions I left class last night pondering was whether or not "social interaction" was actually different from any other kind of interaction between the unconscious and the outside world. Though Prof Grobstein drew in light grey arrows on his diagram of two people interacting showing 6 different ways they could interact, these arrows are of course not actually sources of interaction, but just explanations of how different paths through the unconscious can conclusively connect the story tellers of two different people. What this makes me wonder, is if there is actually an inherenetly different kind of relationship between two conscious beings, or if, as I find myself believing, the inputs our unconscious receives as a result of interaection with another conscious being are just like any other kind of inputs. Sure, these inputs may stimulate mirror neurons, or some other new neural pathway, which until we encountered other conscious beings (in evolution, I mean) we didn't need/have, but aren't the different neural pathways activiated when we interact with other people just that, different neural pathways? Or are they *special* neural pathways for some reason? Why did they get their own class meeting to discuss while all the other inputs to the unconscious got grouped together into one? Perhaps this is because "unresolved conflict" seems more frequently to have to do with our interactions with others, and thus this allows us to set the stage for talking about mental health, but is there more than this?

Also, I felt I left class still not really knowing how to conceptualize or understand the story teller. I feel as though I understand what it does: it allows for consciosness, and acts as a control center to create a coherent story out of the myriad of signals from the unconscious; it can be off when asleep or on when asleep but dreaming; it cannot directly access the outside world, but can interact with the unconscious and vica versa, etc. But in all our talk about it, I still dont really know how to understand/visualize it. It helped me to some extent to understand it when we talked about how there can be different extents of development/use of the story teller - some animals may have a limited story teller, but it is not as developed as ours, for example - because this clarified for me (not necessarily correctly) that the story teller doesn't have an on-off switch, but rather has different levels of intricacy/depth. Is this a correct way to think about it?

more on the unconscious, and the story teller

A seriously interesting question. Yes, in the inputs we get from other people, like inputs from other things, involve action potentials in sensory neurons, and yes, they too get processed in the unconscious before reaching the story teller. But there may well be "special" circuits for doing this. Babies pay special attention to other human beings for example. And mimic human sounds in early speech rather than other sounds. The whole issue of the extent to which there are specialized "boxes" for handling social interactions is an active area of current research (see Social Neuroscience for a recent thoughtful review).

At least a useful way, I suspect. Actually it does have an "on-off switch," as in falling asleep/waking up. But it probably also has "different levels of intricacy/depth." It would, I suspect, be worthwhile to try and characterize these more explicitly. And there are certainly several potentially relevant literatures, including clinical ones, about "states of consciousness."

Case #4

Our group decided that an initial reaction should look into why this patient is wetting his bed, physiologically. Is he on medication with a bed wetting side effect? Did he suffer neurological damage that disables him from controling his bladder while sleeping? Investigating answers to these questions could solve his problem.

There is also the mental "abnormality" in this case that we felt obliged to address. The patient's storyteller is convinced that the patient is not responsible for wetting his bed. Instead, the patient insists that someone else is wetting his bed.

This story, which the patient adheres to, may be problematic if it results in his refusal to be treated for his incontinence. Our first step in confronting his storyteller is to not confront it. We would rather embrace it. We would have the patient elaborate his story by asking him questions such as who is wetting his bed? when is the stranger wetting his bed? why doesn't the patient wake up when his bed is wetted?

We would then film the patient during the night to determine if he is, indeed, wetting his own bed or if his story is true. Presuming that his story isn't true, we would show the patient the film of himself and take it from there.

-Paul Bloch, Julianne Rieders, Julia Lewis

Blaming the patient

Mind-When All Else Fails, Blame the Patient...

This article elucidates some interesting ways in which mental health practitioners conceive of "mental illness." Namely, how the therapist's own "story" about the patient can be limited in some ways. And, as such, the therapist may feel that a patient's "failure" to respond to a particular treatment is the fault of the patient and not a shortcoming of the therapy, or a story told by the therapist that might be too narrowly focused. Additionally, this article touches on the idea that often with depression, in particular, there is a tendency to view the feelings of the depressed person as the cause of depression rather than as an effect. Perhaps, as a society, we often blame people with "mental illness" rather than attempt to understand their story and how certain behaviors stem from stories we tell ourselves, without knowing, perhaps, that other equally "reasonable" stories would do just fine as alternatives... It seems, too, a serious shortcoming in medicine as a whole, often, that blame must lie with the patient when the end goal of "recovery" is not achieved linearly. The patient was "non-compliant" or "treatment-resistant" as the case may be... This seems, to me, to be a set of stories, a line of thinking, which has no benefit for the patient (and may in fact be detrimental).

"non-compliant"

I just read an interested

I just read an interesting article in the Atlantic about children who, from birth, feel that they were born the wrong gender. A lot of this article talks about parents who, rather than try and "treat" this is a disorder, allow their children to live out their lives as they choose. One mother says, answering another who laments that doctors had told her the problem was curable, "Yeah, it is fixable ... We call it the disorder we cured with a skirt.”

In the cases discussed there is still medical intervention necessary (and mental health intervention as well), but rather than treating these children in order to help them conform to society, they are treated in order to feel better in their own bodies. Even in the article not everyone agrees with some of the interventions (particularly medical) made for young children, but it is interesting to think about a perceived "mental health issue" treated in such a pro-individual way.

mental health: sex and gender?

Case #7

In order to understand what about seeing her son's name on the bathroom stall in the girl's room has caused her to be so preoccupied, we thought it would be useful to understand why she feels the way that she does. Implicit in her writing about her experience, was a sense of conflict about her own reaction and, perhaps, asking questions to help her navigate the terrain between her unconscious and her "story-teller" will enable her to capture the genesis of her fears. If the story she created does not, in fact, prove to be a useful one for her, perhaps through talking about it, she will be able to fashion a story that is more useful. We also thought it might be important to talk to her son and see how he feels about the situation and, too, have the mother and son talk together about it.

Martin, Adi, Sophie

Our discussion

I wanted to add a couple of thoughts from our discussion. One of the things that we recognized was that the mother was indeed doing active work to process the story of seeing her son's name on the bathroom wall and the intense reaction it had evoked in her.

It was clear that on some level, her intense reaction made her uncomfortable. I am guessing the writing that she did was a way to deal with the conflict between her unconscious self (which was extemely uncomfortable) and social norms which dictated that she should probably let it go.

Ultimately she did no let it go, she wrote an article in the New York times. That article happened to make all three of us uncomfortable. We all read saw this woman as over-reacting.

Of curse I am guessing many other people resonated deeply with the story that she told (as evidenced by somebody's decision to publish it in the times).

We raised a couple questions in dealing with this "case"

1. Did the woman actually come to us for treatment? If not than we should recongize that she has probably used the writing as a way of dealing with a difficult story and probably does not need any further help reconciling her story.

2. If she did come for treatment - than we would do well to reconize the value of the piece she had written in laying out some of her own conflicting stories. We might be able to help her (maybe through the further writing/journaling) to dig deeper into her stories in such a way that makes sense to her. Having said that again, we should recognize that story that she tells can be very valuable to her and to others.

3. The only qualm that we all had was how her story might or might not be affecting her child. We thought that might be a valuable thing to explore with her - especially in the light of the fierce love that she has for him.

Case #3

This is a case of both internal conflict within the patient and interpersonal conflict between the patient and his father. We would suggest a course of action which addresses the rage and feelings towards his father and also the effects that his symptoms (i.e. the voices in his head) have created in both his life and his relationships (namely with his father) through talk therapy. Simultaneously, we would investigate options for medication and treatment to reduce or eliminate the voices if appropriate. (One might assume it appropriate because rage emerged at finding out his father also had the experience of voices, and this particular response might have been because the voices caused the patient undue stress or anguish?)

Mary Stokes, Antonia Kerle and Laura Jones

Case #2

Treatment Plan:

First, we suggest getting a history and physical exam so that we can be absolutely certain of any physical conditions underlying the mental manifestations. Second, we feel that it is important to support not only the patient, but also the sister emotionally. If she is distraught emotionally (as she no doubt would be) it is important to address this so she can understand fully her brother's condition. Finally, we feel that we should attempt to rebuild the neural connections that have been severed between the tacit knowledge and the I-Function of the patient. This might be done in a few ways. We could attempt to recreate situations between the brother and sister where emotional connections were formed. Hopefully, the situations would help strengthen or reinstate the old connections. Another way might be to appeal to the brother's logical side. If he understood and accepted what happened, he may be willing to spend time with the sister and develop new connections.

Ryan, Katy, Yona

appealing to logic...

I think your first approach (attempt to recreate situations between the brother and sister where emotional connections were formed) would work better.

In such cases, I wonder whether appealing to someone's logical side would be effective since many of these cases are rather illogical. For example, you could get a DNA test to prove that the woman is his sister, but would he be convinced? I speculate that he would find some illogical reason not to believe the hard evidence. It's frustrating because it would be easier to appeal to the logical side if that strategy worked...

Paul, I agree. I also think,

I have a sense

There is a lot of value in that apporach. It seems to me that we often tend to over-value the rational, while completely missing the fact that humans are very similar to other primates in their basic social needs. I found the artcile on Williams syndrome absolutely fascinating.

In that regard it makes sense that when people begin to feel socially secure, their story teller usually can be compelled to find socially acceptable and valuable stories.

giving up "reality"?

Case #6

Contributers: Paige, Riki, Laura

In this situation we would try to get as much information about her routine and experience and try to find a way to calm the girl’s storyteller. One way we could do this is to try and talk her through her experience of believing someone is sitting on her chest, and trying to help her experience what is happening in a less frightening way. We recommend having her keep a sleep journal so she can recall if she was stressed before this happens, and trying to recognize a pattern of behavior so she can come to a new understanding of her experience and create a new story.

SENARIO ONE - Individual suffering from depression post accident

The first course of action would be to have the individual physically re-examined (hopefully an inital examination was conducted) by a medical professional to ensure that there were no injuries to the brain due to the accident. If a physical issue was present then the individual would proceed to be treated medically. To help ease the stress during medical treatment talk therapy would be highly recommended. In the scenario that no physical trauma had been endured the individual would most likely be advised to undergo therapy similar to that used to treat PTSD but not indefinitely. In the short term therapy would be used to explore underlying reasons for the depression, attempting to tie it either to the accident itself or previous experiences that could have preceded the accident and had been repressed. If the bouts of depression were not relieved by therapy alone an antidepressant drug and talk therapy combination would be advised.

Contributors: Valeria, Meredith, Lisa

Post new comment