Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

My anti-self-portrait essay

Relational Definitions of Ourselves

Relational Definitions of Ourselves

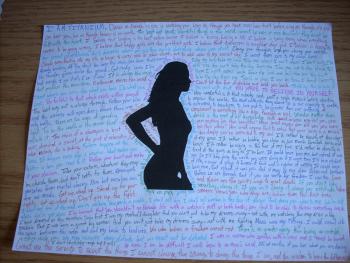

When our professor proposed the idea of making an anti-self portrait, I questioned the idea because I doubted my drawing ability and I struggle with looking at myself. I am scared of what I will find there. However, when Laura Swanson mentioned it could be any medium, I realized that I am not the kind of person who can be represented by a picture, but by words. The words I chose are all inspirational quotes and lyrics either about keeping going even when it is hard, standing up for what you believe is right, or just enjoying life. The outline of the woman is a representation of me, surrounded by all of the inspiration, facing whatever challenges are coming my way and enjoying life. It is purposefully an incomplete picture of me because I defy many categories that people attempt to put me into.

Humans love putting people into categories and not allowing them to change. Putting people in different groups creates a safe place for others. When people know who other people are it is easier for them to interact and it becomes less awkward in conversations and other interactions. People put themselves into categories as well and many times those categories change depending on the situation people find themselves in. When I am in a group that is mostly made up of men, I am distinctly aware that many people define me as a woman. When I am in a group that includes many African Americans, I am distinctly aware of my race. As children, our parents teach us many valuable lessons about love, trust and understanding, and yet they also teach us this lesson of categories.

I grew up with the idea that my family was no different than others. When I talked with my friends, I assumed our differences were interesting, not frightening.

“Oh, you have brown eyes! I have blue eyes!”

“Oh, you have a mom and a dad! I have two moms! That is so cool!”

In the beginning, my friends also found our differences interesting. However as we grew up and the idea of categories came into our vocabulary, we began to fully understand our differences. Today, whenever I attempt to talk about gay rights, people place me in the box: gay. People assume that I am gay because I believe that gay people (my parents included) should be allowed to get married. They act differently around me whenever I talk about my family by attempting to change the subject or just walking away and starting a different conversation with someone else. Eventually, I learned not to talk about any of my differences around them. I defined myself around my high school friends as a radical feminist who promotes gay rights because when I looked around at everybody else in my school they believed very differently than I did. However, coming to Bryn Mawr, I soon learned that I am not as radical as I thought. I listened to many new ideas and people opened my mind to thoughts that I had not considered before. My identity changed when I came to Bryn Mawr. People’s identity changes depending on the situation they find themselves in and who they are with; they become distinctly more aware of how others see them and how they present themselves to the world when they define themselves by what other people are not.

When people walk down the street they pass people who all look different. Humans are very good at giving someone a quick look and knowing some basic information about them just by how they present themselves. I see a white woman with a very expensive bag over her shoulder pulling a small child behind her. Just from that description, I can put her into many different categories. She is an upper/middle class white woman who is probably a mother out shopping with her daughter. When people create categories, sometimes people only see those categories when defining who the individual is. If someone only sees me as a woman, they do not fully know me as a person. Sometimes people attach good attributes to a category, and other times a category can become stigmatized because it is different than the ‘norm’ or those people are the ‘other’ people because I do not have any relation to them. It happens many times with homosexuality. “This process of negative interiorization involves turning the homosexuality inside out, exposing not the homosexual’s abjected insides but the homosexual as the abject, as the contaminated and expurgated insides of the heterosexual subject” (Fuss 1995; 3). We assume that a homosexual can be defined completely by this one category, their sexuality, and we fail to look beyond and see the true person who can also fit into many other categories, or none at all.

Many times we define ourselves based on how other people act, look, or seem to be. We place people in the ‘other’ category and define ourselves by what the other person is and if we are similar to them or not. I am female and my brother is the ‘other’ gender: male. The idea that some people are on the inside of society, or part of the ‘right’ way to live and others are on the outside, or the ‘other’ way to live, has always been a way people define themselves and others:

“It has everything to do with the structure of alienation, splitting and identification, which together produce a self and an other, a subject and an object, an unconscious and a conscious, an interiority and an exteriority…. The notion that any identity is founded relationally, constituted in reference to an exterior or outside that defines the subject’s own interior boundaries and corporeal surfaces” (Fuss 2).

People like binaries because it is easy to compare themselves to people who are the opposite of themselves. Usually, they consider the other person as on the outside of society and themselves as on the inside. Minorities are pushed to the outside and compared with a critical eye to the inside. People question minorities more and minorities have to work harder to be accepted by the public because of people’s prejudices. Humans judge others based on how they present themselves and how they live their lives. The people on the inside could not be part of the inside without the help of the outside defining what it means to not be part of the interior. “The homo in relation to the hetero, much like the feminine in relation to the masculine, operates as an indispensible interior exclusion—an outside which is inside interiority making the articulation of the latter possible, a transgression of the border which is necessary to constitute the border as such” (Fuss 3). The idea that people create a border between themselves and other people helps them define themselves and tell society who they are not. It is easier for people to say who they are not rather than who they are because seeing who they are is sometimes frightening for people.

After people have defined that border between themselves and others and defined themselves based on where that border lies, they then have to present themselves in a way to prove to society that they belong on that side of the border. In Persepolis, Marjane defines herself differently depending on where she lives. When she moves to Europe she defines herself as a Muslim from Iran, but when she moves back to Iran, she defines herself as a world traveler who lived in Europe. Marjane describes “the modern woman” in Iran as “letting a few strands of hair show” and “the progressive man” as “shaving with our without a mustache and keeping the shirt tucked in” (Satrapi 2003; 75). In Europe, people do not consider either of these descriptions as modern or progressive. Europeans would see the description of the man as fairly average, not progressive at all, and the ‘modern woman’ as conservative. Marjane wanted to fit into both cultures and be accepted by those around her so she presented herself differently depending on where she lived and the people she interacted with on a daily basis. She dressed differently and saw herself as more or less progressive depending on whom she compared herself with and what the culture told her. The two cultures: Iran and Europe forced her to present herself differently depending on the different cultural expectations.

Every morning when I get dressed, I decide how I want to present myself to the world that day. It changes from day to day as I think about who will see me. If I am going to class, I present myself differently than if I was going out to dinner with friends, or staying at home and watching a Harry Potter movie marathon. It all depends on which audience I am performing for because I want them to accept me. At home, I am more comfortable so I open up more and am more talkative. In class, I am quieter and am more professional. Some people want to make sure that they do not present themselves a certain way so they take great care to dress in the opposite way, especially if they believe they lack certain characteristics that would allow them to flawlessly fit into the desired side of the border. “The greater the lack on the inside, the greater the need for an outside to contain and to defuse it, for without that outside, the lack on the inside would become all too visible” (Fuss 3). They point to people who are more extreme than they are and because society also marginalizes those on the edges, people push themselves toward the middle and away from society’s critical eye. Nobody likes to be analyzed by other people and so when people push themselves toward the middle, or to the ‘better’ side of the border, they draw less attention to their differences.

People define themselves relationally, depending on who is around them at the time. Their differences only become evident when they are in the minority of a group. People’s differences only manifest themselves when they are pointed out and universally recognized as being a defining factor in a person’s identification. People’s definition of themselves comes from looking at others and placing people in certain categories; usually the correct way to be or the wrong way to be. Our stigmatized differences only become important when they are acknowledged or recognized. I perform for society differently than my brother, who performs differently for society than my roommate. I am usually a very shy person and am sometimes very self-conscious. My anti-self portrait conveys my self-consciousness and how I combat that with all of the powerful words and messages surrounding me and my knowledge that I do not have to fit into society’s defined categories.

Works Cited:

Diana Fuss. "Inside/Out." Critical Encounters: Reference and Responsibility in Deconstructive Writing. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995. 233-240.

Hegel, George Wilhelm Frederich. "A: Independence and Dependence of Self-Consciousness: Lordship and Bondage." The Phenomenology of Mind B: Self-Conscious. marxists.org. Web. 5 Oct 2013. <http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/works/ph/phba.htm>.

Satrapi, Marjane. Persepolis The Story of a Childhood. Paris: L'Association, 2003. Print.

Comments

silhouette

Maya--

I was drawn to your self-portrait—all those inspiring quotes!—and also to the silhouette. I am wondering about its source: was this actually a picture of you, which you turned into a silhouette? Or is it a silhouette of a woman who is not you, which you used to represent yourself? What are the qualities of this figure? What can you tell about her? And what about her represents you? (aside from her “incompleteness,” which you say signifies your defiance of “many categories people attempt to put you into”?). What does a silhouette, as a form, reveal? And what does it conceal?

I think, when Laura Swanson was placing all your anti-self-portraits in the grand tradition of art, that I heard her say your work referenced The Art of Kara Walker, who uses the proper 18th century art form of cut-paper silhouettes to portray the sexuality, violence, and subjugation of African-American experience in this country. I wonder if you are familiar with Walker’s work, and if not—looking @ it now—how you feel about being placed in that heritage? (“inside or out”?).

All this is to challenge your claim that you are “not the kind of person who can be represented by a picture, but by words,” since I start my response by focusing on the picture! In terms of words, your paper works back and forth between personal narrative, graphic narrative, and theoretical text, to argue both that we categorize ourselves and others, for convenience, and that identity is relational and contextual—it “changes depending on the situation.” I’d be interested to know a little more about how you see the relationship between those two claims: how much freedom do we have, to switch up the categories we use? How much freedom to hide those we’d rather not share? (thinking here of your “learning not to talk about any of your differences”).

My anti-self portrait

This silhouette was not an actual picture of me, but I identitified with this picture because she looked like a strong woman who was facing into a storm, but still believed in herself and all she could accomplish. I feel like she is putting herself out against all of the hateful words in the world, but she is also guarded, because you cannot see all of her face. I think this is like me because I believe that I should stand up for what I believe in, but I also am sometimes guarded because it is hard to stand up for a minority group in an unfriendly enviornment.

Looking at Kara Walker's artwork, I do see the connection. I did not know about her work beforehand, but the idea that the people in her drawings also do not have faces and are all black against a white background is very similiar to mine. Her people are in very interesting poses and they are able to show a lot of emotion without using their faces, just their body language. I tried to do a similiar thing with my person.

Some of the categories society puts people in are more easily definable than others. For example, I am a woman and it is easy to tell this so people quickly put me in that category. However, it is harder to tell that I am left-handed except when I pick up a fork or throw a ball. Usually the most obvious differences are more stigmatized, race and gender because people see the differences easier and they feel more uncomfortable about that. Sometimes it is not easy to hide that fact that I am have two moms because people ask what my dad does for work. I have never tried to hide the fact that I have two moms and because I can just talk about one of my moms at a time, it is easier to just not mention that I have two moms.

I thought the threading of

I thought the threading of your personal anecdotes and theory was done really well. We have similar ideas where we consider outside perceptions of our identity, and how they effect our self-performance. Whether that effect be belittling or empowering. I like that changes in perception and definition of identity can be every-changing. Your quote anaylsis was excellent, but my only suggestion would to maybe instead of saying humanity or society as a whole, mentioning more about the society that you grew up in or in now and how effect your viewpoints on your ideas throughout the paper so your ideas carry through.

Terminology

Seeing how we used a couple of the same texts in our papers, it was pretty interesting to see what directions each of us took with what we read. While I was very theoretical and perhaps philosophical about the idea of categorization, you decided to explain it visually, using scenarios that everyone finds themselves in at least once in their life to make them think about the impact categorization has on their lives. You also touched upon the idea that our identities as human beings are always changing. This compares to the claim that I made in my paper that identity is not a stagnant, singular entity. Your use of the self/other dichotomy was a way for you to show how binaries are designed to exhibit opposing forces. I try to do a little bit of this myself in my paper using Diana Fuss's "inside/out" terminology. Something that you explored in your paper, that I did not, was the idea of culture and borders. By using "Persepolis", you were able to take the inside/out figure to both a figurative and literal level, by comparing how Satrapi sees and identifies herself before and after her trips to Europe. Overall, while we both had many of the same meanings and interpretations when analyzing the texts, we decided to present them in differing, although not opposing, ways.