Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Brain, Education, and Inquiry - Fall, 2010: Session 2

Session 2

Class is itself an experiment in a particular form of education: co-constructive inquiry

Learning by interacting, sharing observations and understandings to create, individually and collectively, new understandings and new questions that motivate new observations

Depends on co-constructive dialogue, being comfortable sharing existing understandings, both conscious and unconscious, in order to use them to construct new ones. Need diversity of understandings, need to be able to both speak and listen without fear of judgment. Need to see both self and others as always in process, always evolving.

Starting where we are: from the forum

If education can be defined in so many ways and if so many people disagree on what exactly education is, then how does it work as a subject of study? Aren't you then studying what you are participating in? how does that work exactly? ... ln0691

because "education" classes in college are about academic education we naturally assume that this will be the topic of discussion, and cater our thoughts to meet this expectation. Thus we begin talking about education as it relates to school, and are now taking a step back and saying, "wait, isn't there so much more to education?" During class I was thinking about how our setting is affecting our discussion and I wonder if there are other ways, in addition to how we're thinking about education, in which our setting is creating subconscious biases ... evren

Like many people who have posted, I found one of the most thought-provoking (and at the same time frustrating) things about our first class to be the labels we tossed around ... epeck

I feel, as it seems several of my classmates do, that it might be useful for us to begin at or somewhere near the/a beginning: what is (an) education, really? ... Just because we are in school does not mean that we know what education is ... bennett

I thought it was really interesting to see how the responses to the ‘Brain Drain’ covered a broad spectrum ranging from apples to policy. There were also some recurring words, though, like grades, students, etc. What struck me, however, was how presumptive we were about what people meant. The two people who said grades, for instance, probably meant very different things. I feel like it’s things like this that create a disconnect in general conversation as well. When we don’t define our terms, we end up talking at each other or past each other and that creates confusion and misunderstanding ... Ameneh

what "unconscious biases" do we bring to a classroom because its a classroom?

what is education "really"? who gets to define it? why? how?

Maybe the place to begin isn't actually with "common definitions" but rather with whatever each of us happens to be thinking at the time we start? And out of that comes (or doesn't come) "common definitions"? ... PG

We wax poetic about the failure of the school system and of teachers and administrators and everything in-between..... but truly, many of us are a product of many of the same systems we berate. The scholars and businessmen and white-collar and blue-collar workers, the activists, the tycoons - we all are products in some way, shape, or form, of that system. Surely the system coulddn't have gotten everything wrong. So the question becomes: "What did the system get right? What has it so far done correctly? ... Kwarlizzie

What I find frustrating about education, and a possible reason that it can seem shortsighted, is that good grades enable an individual to ostensibly have more options (this point is also debatable!), and grades are usually given periodically during a semester and the accumulated grade is given at the end of the semester. This system is very fragmented, and when grades, evaluations, and judgments are given in this way, and given such great meaning, then it becomes difficult to keep perspective. How much does our flawed educational system have to do with how we are evaluated (i.e. grades and standardized tests)? ... FinnWing

As in many of the quotes above and the observations in class, education is usually linked only with value as a means to success, not for its own sake ... memyselfandI

Thinking back to my most formative times as a child, and now as an adult, very few of them occurred within the walls of a formal teaching institution. These times occurred as a child, playing with my sisters and interacting with my parents and grandparents. I believe that it was during these formative times when my mind was most open and impressionable, not when I was studying in college or writing a paper. Perhaps the difference is that, in grade, middle, and high schools, as well as in college, I was given assignments of what to study and topics on which to write papers and was not allowed to let my mind wander in the same way that it was able to when I was a child playing in my Nanna’s attic ... Angela DiGioia

many of the things that "aren't working" in our educational experiences aren't working because we misunderstand and feel dissatisfied because we have the wrong expectations. Education isn't a thing, but a process. I guess it's true that, for some people, years spent in school are dues to be paid or time to be logged in purgatory before getting your golden ticket diploma to fame and fortune, but I sort of feel that it can't be a "good" education if it can be treated instrumentally like this, if it changes you so little that you have the same goals before, during, and after its acquisition. I accept that degrees and money exist, and that they do influence the shape of our reality. But they're really just pieces of paper. And they only mean things because we agree to believe in them. Ideally, the process of education should feel more tangible, more perception-altering and reality-influencing than those pieces of paper ... jessicarizzo

if we accept that "knowledge is power" ... what is this power, and why is it so important to have it? ... do we actually get that "power" or are we feeding into a system that only makes us believe we have more control than we really do? ... kgould

the purpose of education is to reestablish social norms and to maintain and feed into the existing societal structure…its to keep the people at the bottom at the bottom and visa versa, to separate the “have” from the “have nots” ... L cubed

Education either functions as an instrument that is used to facilitate the integration of the younger generation into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity to it, or it becomes the ‘the practice of freedom,’ the means by which men and women deal critically and creatively with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world. … Richard Shaull, introduction to Paolo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 2000 (republished from 1970)

It is this predominantly smooth move on the school-based education "highway" that can cause the passenger more fatigue than frustration. The frustrated passenger is the one who has yet to reach his/her destination within the normative time, personally anticipated time frame and/or at all ... D2B

We learn by watching, doing, mimicking. We tell stories. We remember. We recreate situations. We regurgitate information ... Do we learn to be more efficient? Do we learn to survive? How much of learning is done on purpose or consciously? ... eledford

"where is the fun in all this?" ... My instincts tell me to have fun with school (and with life in general) in whatever way I can ... LinKai_Jiang

What is/should be the objective of education?

to have fun, to acquire information, power? to achieve knowledge, understanding? to participate in the transformation of the world?

Can thinking about inquiry and the brain help?

What is knowledge, understanding?

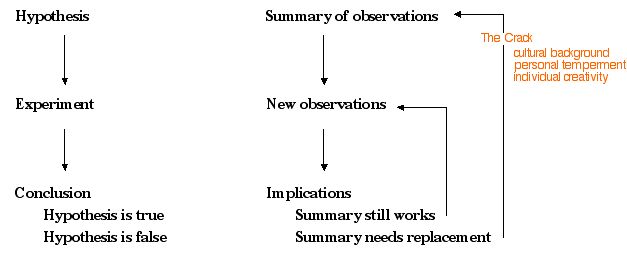

talk about in the context of science see Science as Story Telling and Story Revision, and then of empirical inquiry in general

| Linear science | Seriously loopy science |

|

|

|

Science as rooted and tested by empirical observations rather than authority Science is about the natural world Science as body of facts established by specialized fact-generating people and process Science is about objectivity Science puts aside values/aesthetics Science is about Truth, the provable, the universal Science as successive approximations to Truth

Science is about discovery of what is Science provides authority, certainty |

Science/empirical inquiry as rooted in and tested by empirical observations rather than authority Science/ei is about the inanimate, the animate, and the human Science/ei as ongoing process of getting it less wrong locally, potentially usable by and contributed to by everyone Science/ei is rooted in subjectivity, aspires to shared subjectivity Science/ei uses values/aesthetics and contributes to themScience/ei is about doubt, skepticism, the possible, the shared Science/ei cannot establish Truth or proximity to it, as ongoing making of observations, intepreting/summarizing, making new observations, making new summaries, a continual looping between one's understanding and the world, as well as among different understandings in different people Science/ei is about creation of what might be Science/ei denies all authority, including its own, is about the generative capabilities inherent in uncertainty |

- Multiple stories for a given set of observations

- 3,5,7, .... ?

- Stories always context-dependent

- 1+1=2 or 1+1=10?

- Is where culture, individual creativity as well as reflective thought (formalization, deduction, induction, synthesis, abduction) play an important role

- Observations in turn depend on stories so story choice influences future science

- Science is as much about creation as about discovery

All understanding, in the sense of empirically based knowledge is tentative, subject to revision based on new observations and/or new stories (looping)

The quality of empirically based knowledge at any given time is related to the number of observations summarized, the number of different ways of accounting for those observations (stories) that have been considered, and the imagination of those generating stories. "Objectivity" is "shared subjectivity."

Empirically based knowledge is useful in contexts similar to those that have contributed to past observations, and useful in motivating new stories, questions, and observations

Empirically based knowledge should always be treated as a foundation from which new knowledge can be created, rather than as an end in itself.

"Knowledge," in the sense of empirically based understanding, is summaries of past observations with expectations for future observations, a starting point rather than a final word. Knowledge is always subject to revision, either based on new observations or on new stories or both. And always has an element of uncertainty to it. Acknowledging uncertainty in existing knowledge gives everybody the the ability to play a role in creating new knowledge.

Re education: objective is not to acquire knowledge but to acquire the means to create it? to "discover how to participate in the transformation of the world"? (Will take a closer look at understanding later; keep in mind "loops")

Are studies of the brain relevant? If so, how? (see also course resources and Chapters 1,2 of How People Learn)

|

The potentiality

|

All knowledge/understanding is a product of the brain, a construction by it, a "story"

Education is a changing the brain, according to one or another particular story about how/why it should be changed, so knowing something about the brain must be relevant for education

"The truth about stories is that's all we are ... If we change the stories we live by, quite possibly we change our lives" (Thomas King, The Truth About Stories) ... and our educational systems?

Your continuing thoughts about inquiry/brain/possibilities/problems in the forum below ....

Comments

grades

Someone in the last class mentioned that "grades have become an end rather than a means." I completely agree with this statement, but still find it hard think of other ways students can be evaluated. Grades are supposed to be a tool to give us a better understanding about where we are within our education, but once that tool becomes the only thing of focus then how are we as students supposed to grow? I know when I was in high school, when there were multiple assignments due each day and all of them got a grade, I stopped caring about what I was learning about and did just what I thought the teacher was looking for. And all for just getting a good grade. Once again though, I'm still stuck as to how we can change that "good grade philosophy" (especially for secondary school students) or how we can change the way people are graded at all. Because, at the end of the day, we do need some sort of indication on how we're doing in our education. A few people mentioned getting rid of grades all together, maybe having written critiques from teachers. I think this is an interesting idea and could possibly work but I don't think it's very realistic. There is already a huge lack of teachers needed in the United States and all around the world, and some teachers have many more than one class with numbers of students reaching 40 per class in some public schools. How are we to expect these teachers to give descriptive progress reports all the time instead of a grade when it would be much more time consuming on their already hectic lives. I'm open to more suggestions as to how we might be able to alleviate this problem or at least change the way grades are used and perceived.

We live in a society where there is a huge amount of weight placed on grades, as education is a highly competitive system. And sometimes I can't help myself from going into that sociological part of my head that keeps saying "What are grades anyway? Aren't they just a social construction? But if they're a social construction, doesn't that mean they're now real because society has made them real? And if they're real, can we really live in a society that so heavily pushes higher education and not have grades at all?" Then there's the grading policy for this class where we're not getting grades, but really we still are. There are some people who need a grade to really understand what they're learning. Are we supposed to fault them for that? Shouldn't we be open to all types of evaluation. Is it really fair to say "here's a 3.3 cause you did what you needed to do, but it still wasn't that special"? Even Paul said that all people don't learn or achieve in the same way and ranking everyone on a single scale of grades won't do anything for their education. But what if one of the ways some needed to learn and achieve way through grades? And then I think of what someone else said in that class that "it's the business of education to change society." Ok... so how? While education has developed and evolved over time, there have been grades for a long long time. Are we going to have to wait another hundred years before something different starts to come out of the woodwork or do we need some sort of major grades revolution? I don't know.

Structure and lack thereof

The definition of the objective of education as "the means to create knowledge" makes sense to me, but I'm not sure I entirely agree with it. I think it's important to keep in mind that we do need to have some basis on which to build. We can't just start creating knowledge out of the air, nor can we then rely on what we have created because it did come out of thin air. Perhaps the objective of education is better put as "to acquire knowledge in order to create more knowledge"?

As far as the structure arguments go, I am biased because I definitely like structure. I like knowing the rules, exactly what I should be doing, and how it's going to be evaluated. That being said, I feel that in class and here in the forum structure is getting demonized to some extent because of the conception that structure means forcing students into certain pathways without allowing any time of freedom. I agree with D2B's comments above (or below, I guess), and I would take it even one step further: that structure and room for creativity are not mutually exclusive. I have been in many classes where I have been assigned an essay or a project, complete with a rubric for how it would be graded, but I would be able to pick my own topic and take the idea(s) in a direction of my choosing. I really think there is room for creativity and structure to exist side-by-side. If this type of learning needs to be encouraged instead of diminished so that it takes precedence, then so be it.

I'm not really a "science person," and as I said in class, it's been years since I've thought of anything as immutable fact. Everything is relative to something, be it personal experiences or knowledge or someone else's opinion. So the "loopy science" model wasn't super new to me. I am curious as to how exactly it would be implemented into the education system, though. The logistics involved, like those in the article we read, seem nearly impossible to reconcile. I hope to touch more on logistics in class tonight.

Seriously Loopy Science...Not so Loopy at All

Previously, I mentioned that many of my peak education moments have come outside of the classroom. I’ve been exploring this further to pinpoint that top ten to twenty peak education moments that I think have been the most formative in my education as a child and as an adult. Most of them involved my parents or grandparents in some way but some of them also involved a teacher that I’ve had somewhere along my educational career. Interestingly, these peak education moments were interactions that occurred outside of a classroom and, more often, in a social setting. I remember one interaction specifically where a teacher kept asking me questions in response to my questions. At the time, I was frustrated and somewhat uncomfortable because I thought that my questions were not being addressed and that I was being judged but, I later learned that this was a technique called “Ask ‘why’ 5 times.” I still go through the exercise in my head often if I am pondering a question or trying to get to the root of an issue.

One of the benefits of “seriously loopy science” is that unconventional methods, such as “Ask ‘why’ 5 times,” are means by which both individuals and teachers can learn about each other and look introspectively to explore their observations. To me, learning is a cyclical process; every bit of new knowledge is based on previously existing thoughts (conscious or not). To me, this is what the goal of education ought to be and not memorizing numbers and fact without ability to apply them to actual situations. What use is knowledge unless you can apply it to situations in your daily life? Theoretically, wouldn’t the purpose of knowledge be to create more knowledge (or thoughts) and to keep pushing the boundary further and further? I think that “seriously loopy science” is the way that our minds work intuitively and that one would be hard pressed to argue otherwise. After all, even science wonks use this methodology when publishing papers (although perhaps they would probably argue otherwise). Accumulation of knowledge and further exploration of the unknown (which is pretty much everything) is the matter of which scientists are in hard pursuit. Will we ever answer all of our questions or be able to explain all of our observations? I hope not. If we do, where will go from there?

What are we learning about?

It was natural for me that substantial learning entails getting to know something outside of yourself. Things like feelings, emotions and inner intuition are for private entertainments and pastime materials with friends. It was so natural for me, and perhaps for many others, that those “subjective” elements of the self are not appropriate for intellectual inquiry. The thought was partly influenced by the rigid elementary schooling I had received. What mattered was the precise calculation of numbers and equations, and the correct definition of words and their proper usage. Even when creativity was encouraged, I thought I was supposed to be creative with things “outside” of myself. I did not really question the epistemic limit that others had set for me and I, myself, had reinforced.

The rebellion against this prescription sprouted as I felt discontent about the coldness of knowledge. The capacity to do well in school does not automatically engender a passion for it. Fortunately, the urge to be righteously subjective was given the opportunity to be expressed and explored. It has been that subjectivity, no matter how little, that sustains a meaningful connection to “objects” of knowledge.

The denial of the subjective is troublesome in another way. Calling things we’re learning “objects” of knowledge implies the dualistic divide between the subject and the object. I do not want to say that the divide does not exist but it is not a clean cut division. What we perceived as the “object” of knowledge has to be processed through our mind. So to constitute an object a subjective processing is implicated. Kant calls this filter the categories of understanding. Since we’re looking at the brain today, I’m interested to see how those categories of understand are manifested in the physical structure of our brain. Somehow I feel it is a long shot, but worth the exploration.

As of now, I completely agree

As of now, I completely agree that “the objective of an education is to acquire the means to create knowledge.” I also agree that structure is in a way ever-present and necessary, whether it be within or beyond the confines of the classroom, in building and creating knowledge. But when, if at any point, does structure inhibit the very knowledge that it is trying create? At some point structure becomes a barrier rather than a means. In many ways, I think that the structure of school, more specifically college, does not adequately support the creation of knowledge. In my own experience, I feel like I have spent way too much time in the classroom listening and discussing and not enough time out in the real world discovering, doing, experiencing. Not that these things cannot or do not occur within some classroom spaces, but they simply do not occur enough. Consequently, there just seems to be a very strong disconnect where nothing is really made tangible and our own creations of knowledge are….invaluable, I’m not really sure if that is the word I’m looking for.

In response to what some have said, while we do tend to foucs on the ills of the education system, I do think that one of its "things done right" is providing us all with a common foundation and basis for some kind of learning. Like Abby Em said, while this may seem pointless at the time being, it is helping to build skills that are useful in life....But what is useful in life? That seems like a silly question, but I do think that it has some validity and that the answers vary across cultures and even from person to person- just a thought.

I do not disagree with the

I do not disagree with the statement that the "objective of an education is to acquire the means to create knowledge". I think it points to something with golden intellectual value: the ability to create knowledge instead of the burdensome accumulation of it. But one can ask further, "what is the objective of acquiring the means to create knowledge?" in other words, why do we need to be intellectual at all? I do like intellectual activities, but i always return to this question. I'm wondering if anybody has similar doubts.

Aim of an Education

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

X-NONE

X-NONE

MicrosoftInternetExplorer4

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:"Table Normal";

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-priority:99;

mso-style-qformat:yes;

mso-style-parent:"";

mso-padding-alt:0in 5.4pt 0in 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0in;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:11.0pt;

font-family:"Calibri","sans-serif";

mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri;

mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-fareast-font-family:"Times New Roman";

mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast;

mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;

mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin;

mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman";

mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;}

An education in general should be able to provide students resources that can cultivate mental and social skills, along side of the “tools” and “facts” necessary to promote knowledge, thinking and learning as Abby discussed. Education should be multidimensional and interdisciplinary. Students should be able to make connections with what they're learning in all of their classes and not only apply that knowledge to other classes (based on the skills that are being taught and emphasized), but also apply it to real life (those life experiences we acquire outside of the classroom on a daily basis).

Education should be conducive to different types of learning (not just visual or by ways of hearing) and engage creativity (to broaden the mind and add dimension to the useful structure an education is said to have), more so in science and mathematics classes.

Most importantly, education should be culturally inclusive, not just another representation of any normative, which would allow for new observations, challenging new horizons, new ways of thinking and new possibilities can be learned until one reaches a solid and better-rounded idea/thought or perspective. This aspect of what an education should entail in my opinion reflects what science aims to do. If there is a new observation that a scientist makes and it invalidates the original one, then we discard the previous observation. An observation is the first step in the scientific method, which leads to these new ways of thinking to broaden and extend this field of inquiry. By scientists observing their surroundings it ultimately can help reach an idea of reality or it helps us reach a wrong result (we also have the power to avoid such results). However, science is a type of guide in itself allowing for this transformation of thinking, which contributes to knowledge. This same process I feel holds true for creativity and our sought after life experiences.

Lastly, to just briefly touch knowledge as a context of science, I view science as a form of knowledge. Science loops back and forth as far as I’m concerned between information and knowledge because as new Information is achieved, it changes our current understandings forcing us to re-examine our previously held beliefs and alter them in accordance with this new information, which, of course, alters not only our “wisdom” but insight, awareness, etc. With that in mind, I also view the information we collect about our surroundings with the help of our five senses to be a form of knowledge.

Structure within learning

Very often I feel that in order to succeed within school you must know how to work the system. Knowing parameters and measurements help you measure your own potential success within the structure. It is less about your own personal will to always do as you are told and more about doing as you are told to get the results you want the system to record. But you cannot deny that insomuch as you are not aimlessly wandering through a course, intellectual stimulation within a creative space is not only attractive but highly beneficial. More so, I do not think that creativity is synonymous with a lack of structure.

For example I consider this course to be very creative based of the fact that there is material to be learned yet the use of one's own experiences, opinions, academic and non-academic learnings are very important and influential for the course. There is still structure to this course and material to be learned but our minds are allowed to wander and self-willingly wander within the parameters of the context of this course.

In no way am I supporting absolute riddance of all structure within education. However I highly support creative spaces within academic structure because they have proven to create more engaged, knowledgeable, and attentive learners and teachers. Additionally, it is often the case that within creative spaces students indeed learn necessary skills and material without even realizing what they are retaining. It is then that the learner can be or is tuned into the fact that they have learned the basics through engaging with material creatively.

I find myself, as you can see

I find myself, as you can see from my last post, wanting to defend the formal education system, not in all it's forms and, certainly, failings, but as in institution that aims to do the right thing and sometimes succeeds. Oddly, for the first word association exercise with "education," I was one of those who gave none school related responses (children, people, life,) yet when we keep reiterating that "people thought about classrooms when they heard education" I get defensive of those classrooms that our conversation is saying don't provide as much learning as the ever-hallowed "life-experience." Plenty of learning does go on in school, it's just more foundational, less spontaneous, and not often as distinctly memorable as those learning moments that happen in the real world. As much as the aha! moments of understanding or new ideas reaffirm the joys of learning and stick out, a background and continued experience with formal education primes us to get the most out of those moments, enabling us to draw farther reaching conclusions, ask the right questions, and articulate their importance to others and to ourselves. We do take school for granted, not just because of socio-economic privilege that makes it's availability unquestionable, but because the simple demand that learning be fun is overshadowing the more nuanced truth the learning be worthwhile and rewarding. In truth, not everything of value is fun. Even rewarding school curriculums would not be deemed "fun" in comparison with just playing with friends all day doing whatever you chose, but it far from makes them worthless.

The article we read on "How people learn" helped me focus some of my thoughts by drawing my attention to two separate, sometimes seemingly competing, but actually interconnected types of knowledge taught in school- tools and facts. For a long time for me, I've considered classic complaint that "I'm never going to need to know this formula/ French history/ the themes in Beowulf in the real world" to be foolish, not because it isn't true, but because it misses the point that you're being taught to *think* with these examples. It's a kind of learning that happens slowly and gradually even when properly taught, such that you could seemingly argue that you're getting nothing out of having to write a paper analyzing a character's growth in the Odyssey. Maybe not on its own, no, but repetition is valuable for any kind of training, in this case the training to organize your thoughts, draw conclusions, express them deftly. I believe that we're all better off now for being taught that, even if at the time it was not considered fun. And of *course* we want to have as much joy in learning as possible, both for effectiveness and just for its own sake, but there's a certain kind of discipline required that is inherently less fun than if you were able to just do what you wanted.

To get back on track, this article helped enrich my understanding of school as something that just gave you tools to learn more and think better by explaining how providing a solid bed of factual information is itself a tool for learning more and drawing more sophisticated and potentially original conclusions. It taught right, in a way the we remember and incorporate it into our knowledge base, knowing "stuff" is, they're right, quite valuable. I would not know this much stuff if I wasn't presented with it in an organized setting, I simply wouldn't. Life experiences, all the day to day learning experiences we have, are more valuable to us because of our knowledge ("things") and thinking ("tools") base we get in school. I just feel it's all too easy to criticize the institution, and that formal education is an easy target of our disdain that we're in danger of beating up in our efforts to feel liberal-minded.

I think we definitely need to

I think we definitely need to be guided in our intellectual quest. At the beginning, I would want somebody to teach me the foundation of mathematics and the basics of the language and other things. Many people would be severely deprived if they were not "babied' during the early years of their education. But the problems with formal education really emerge later when we have achieved a solid foundation (of course how much is enough foundation is up for debate). Then institutional structure continues to serve what they are best at, but which we do not need anymore. I should qualify this by saying that in education one can never do without some sort of "guidance" but I do not think we need to be in school or any institution to get those guidance to take us further intellectually. What the institution does best from this point on is to socialize us into certain norms of intellectual practices: learning the right jargon, citing in the right format, picking the right topic to write about...etc.

Positive Reinforcement

Reading Simone's post got me thinking more generally about how to encourage students. While her example perfectly demonstrates how seemingly innocent compliments can actually negatively affect the growth of a student's creativity, similar influences can hinder student growth in what are classically considered less artistic areas of academics. It may seems innocent to tell a student that he or she is smart, intuitive, etc., suggesting that there is an innate ability. However, such suggestions lead students to believe that their academic ability is not in their control and that they either can or can't, regardless of who their teacher is or what effort they put in. On the other hand, by acknowledging students' diligence and effort they develop stronger work habits and ultimately develop their abilities more than those who believe achievement is innate.

teaching creativity in school

Building off of what Ameneh said above, I certainly agree that asking creativity in school, and then in some way qualifying or assessing it, is a sticky realm. I volunteered with an organization that brought visual art classes to middle school kids for a few weeks in San Francisco. During training it was explained to me that we, the mentors, were not allowed to give our opinions on any of the kid's work. When a authority figure tells a child that their painting is good, nice, or well-done, they naturally try to re-create that response, playing to our aesthetics as opposed to their own, and recreating old work as opposed to being truly and spontaneously creative.

In school settings surrounding creativity, what is the role of the teacher at all? Besides to make sure that we were not eating paste or running with the scissors, I personally felt that all of my art teachers in school did more to hinder my creativity then nurture it. They let us know what the objective was for our project, and inevitably certain students stood out as "better" then the others. The teacher was partially impressed by their work, they developed the ability to draw an apple or paint an accurate self-portrait before the others.

I've seen the linear vs.

I've seen the linear vs. loopy science model over seven times now, in class and during summer research, and this is the first time that I've really thought about using them together rather than choosing between the two. I am a fan of loopy science. Not necessarily the model of loopy science, although that's pretty awesome too, but the ideas that go with it-- science is not the final word, it denies authority including its own, it is not really "objective," it is not a matter of "true or false" or "right or wrong," but getting things less wrong and always, always retesting hypotheses.

But what if we were to use the linear science version together with the loopy science version? Is that even possible? Someone suggested it in our last class and I'm curious about what that might mean. Yes, the models are similar and they suggest similar processes, but it is the approach to each that is different. I don't think the attitudes of linear science could reconcile with loopy science's more open-ended approach to exploration and understanding.

Linear science is about discovering "what is." Loopy science would argue, I think, that we can't ever be sure about what is. How can we know anything we discover is true? One instance of seeing the sun rise does not mean the sun will rise again. One instance of seeing a molecule behave a certain way doesn't mean that it will behave that way again.

And I think education is divided along these lines as well. I know that I had a more linear approach to learning in high school; the teacher was the authority and you did not, unless the teacher was secretly "loopy," question them or their authority. You went through your observations, your exploration of a topic, you drew a conclusion and it was either the right one or a wrong one. There was always a "right" answer and, often, only one. If your English teacher didn't think that your paper agreed with what they said in class, you didn't do well. It was less about learning for yourself than playing into what you knew the teacher wanted. And that's not really learning.

finding sense in a wirlpool

we spoke about a lot of different thigngs in class - ideas and concepts were thrown around and new ones were created. amongst everything, a few particularly stuck out to me.

what are some of the consequences you run into when you study something you're a part of? this is question remained with me, mainly because of the answer someone provided for it - when you study something from the inside out, you gather observations and information from the outside, drag them back in, work with them and through them, and you realise that you can change things. why is this important? because it gets rid of the feeling of helplessness. because knowledge aqquired from the inside gives you the power to do something. when looking at things from the outside, no matter how involved you are in them (be it science or a global problem or even a social problem), you're often faced with the realisation that theres only so much you can do - theres only so much you can touch, or change, because try as you might, you cannot always change how another person or system operates.

and as far as education is concerned, this is important. by taking this class, we're already changing our approach to education, we're already questioning things and dissecting concepts, to find a ground we are comfortable with. we're changing the way we educate ourselves. does this all go to hell if we dont become teachers or administrators? not at all. because, we build a ground on which we approach education differently - we approach it differently when we teach our children, or when we teach a company a new concept, or even when we have a conversation. we're constantly learning, and now, we're giving ourselves a basis to learn differently, maybe even more effectively.

another question that stayed with me was that of an educational peak and whether or not students reach that in the classroom. as far as i can tell, i reached my own educational peak outside of the classroom, but as a product of the learning environment i was in. my classes themselves weren't great and i hated the curriculum, but i learnt with my friends, through conversations and experiences and ideas we shared. and these are friends who were products (partially) of the same system i was. and i cant help but wonder what it would turn out like if we integrated culture and exxperience into the four walls of a classroom. would we help students reach that peak inside the classroom? or, actually, how important is it that that peak is reached within the classroom?

In class we talked about

In class we talked about grades and their inadequacy. After thinking some more about it, I am not sure there is anything wrong with grades. I think what is wrong is the way in which we use it. I think some arbitrary marker orf progress, if you will (grades) is needed in the academic world, so there is nothing wrong with giving grades. What is wrong is when we expect grades to be the only marker of what is happening. I don't think grades are supposed to measure temperament, or individual skill, or individual creativity. It is we/employers/the system who have forgotten that grades are only supposed to be a marker for how well a concept is grasped.

In the same vein, it is not up to grades to tell us how individual students learn.... it is the job of the education system/teachers to vary teaching styles and pay attention to individual students and notice how we learn. Of course some teaching styles are always going to help some students more than others, and so it is up to teachers to vary teaching styles, or account for the differences in personalities that we all have. Of course all this is easier said than done given the realities of teachers and students and classrooms and education systems. And it is up to employers/students/teachers/everyone to realize that grades are only one arbitrary marker of knowledge and not the whole thing - in fact, not even the most important thing.

In class, someone brought up

In class, someone brought up whether or not the system did get anything right. Although I agree that giving students “creative freedom” in their education can produce interesting results, I also feel like its is unfair to assume that all students want creative freedom or dislike structure. For me personally, I rigid guidelines for what I am expected to do. Take this class, for example, we were told that everyone would get a decent grade if we did everything we were told to do and to do better than that we would have to do something different, surprise ourselves. I wonder why just doing as you’re told isn’t enough, if you do it well? I understand that students may feel inhibited, limited and powerless when they’re told exactly what to do and how to do it but its contrary can be equally harmful. By asking or expecting students to be creative, wouldn’t we unconsciously make things harder for those who don’t want or need that creative space, not because they don’t want the effort, but because it’s just not their thing? I wonder if it’s possible to allow students to choose what system of education they prefer. Have structure for those who want it and creative freedom for those who don’t?

"I wonder why just doing as

"I wonder why just doing as you’re told isn’t enough, if you do it well?"

Because then you'd just be a cog in a machine right? How do you feel about that? How do you know that the person telling you what to do has your (or anyone's) best interests at heart? They might be, say, a fascist dictator... and you're the one throwing up your hands saying, "But I was just following orders!"

Not necessarily, actually. I

Not necessarily, actually. I meant specifically within the four walls of the classroom. If a Philosophy Professor goes hey, for your paper write a page about what you got from the reading Aristotle, a page or two about whether you agree or disagree with what he says and a page or two about your opinion, I fail to see what the issue with this would be.

language-style education

Language acquisition came up as an example of learning that occurs without structure and really much “teaching.” Language is picked up on easily and cross-culturally, with most rules understood although not usually taught. As we were having this conversation, I kept thinking that language was an “unfair” example, since it is learned in such a different manner than other skills or subjects, and should really be in its own category. I started thinking about what else would go into the category of things learned in a similar way and came up with skills like eating, walking, running, smiling…and more sophisticated things like mirroring, sarcasm, ways to manipulate the behavior of others…etc.

All of these things are either necessary for survival, or are extremely social. As was mentioned, babies learn quickly that if they cry, they can easily manipulate the behavior of those around them. This type of behavior is somewhat sophisticated, yet required no explanation or training. Although I do think these are somewhat “unfair” examples to show that structure is not key to learning, it would be interesting to try to develop a system of education based on social learning. If children can easily and naturally learn things like language because it is a necessary social skill, can we somehow make reading or chemistry into a “social skill”?

If you want to quickly learn a language, an immersion class is extremely effective. If you read often to a child, they may pick up on the skills without ever being formally taught. Would this kind of immersion/social setting work in other subject areas? If you took an “immersion science course,” would it be possible to learn the basics of chemistry just by observing others doing problems are being put in a situation where you have to work with others to figure out problems with some of the students never having formally learned the material?

What to Teach

I was reminded of my 11th and 12th grade Biology classes when we started taking about the difference between linear science versus seriously loopy science. Prior to those two classes in middle school and 9th grade, we had been taught the linear science rule of thumb which we then used in our labs. In 11th and 12th grade, however, we were taught the seriously loopy version of science, but not in a direct manner. Our teacher was up in front of the class and told us something along the lines of "when you are typing up your labs reports, make sure that in your conclusions you don't say that the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. Instead, make sure to say that the results support or do not support your hypothesis." That was all that she said on that matter, there was little explanation given as to why we should phrase our conclusions this way but I did know that if I said that my results proved my hypothesis rather than supported my hypothesis, a great number of points would be deducted from my lab grade. Near the end of 12th grade Bio a student asked why we were supposed to phrase it in such a way and my teacher initially responded "because that's the way that IB tells us to" and then paused for a few moments before launching into a description of seriously loopy science. I find it strange that my teacher had the opportunity to show us the "crack" that exists in science but chose not to until the end of our 2 years in her class.

Looking back on this, it makes me think that my teacher's choice created a class that was somewhat of a contradiction. On the one hand, we had the idea drilled into our heads that hypotheses couldn't be proven. On the other hand, this idea was not used to challenge the structure of traditional science classes, rather it became part of this structure because a our teacher did not really incorporate it into our learning. At the same time in this class, we were being taught material that was specific knowledge that was deemed to be true by IB and our teacher. In that way, the encounter with seriously loopy science really only became a part of a linear science method of teaching. I wonder if such limited deviations from the traditional structure of education really do any good, or whether when they become a part of the structure they lose their weight and purpose.

Narrow is the path of.... structure?

To learn feels good. Education is tool that I feel can broaden one's mind or can narrow it, especially if the curriculum is exclusive of other materials, insights, or methods.

I think I like structure, or am I just used to it? On the basis of clarifying, to me, structure means a certain organization or direction. Maybe each of our minds have been sculpted by our early molders (primary/secondary education) to respond to structure in certain ways... that's why some of us thrive on it, and others steer away from it. Perhaps having too much structure has its consequences. Sometimes I find myself struggling when given little direction for an assignment or a project.

Education today is still very structured and perhaps it inhibits individuals from thinking out of the box, breaking out of the norms that we participate in, in order to "transform" the common way of thinking. We briefly discussed that a group of homogeneous individuals that think, act, or do, is much less effective than a heterogeneous group. Perhaps the way to enhance the mosaic is to have less structure. Or maybe its better to say that from the beginning of one's formal education (in the form of going to school at the age of 5 or so), there should be a greater emphasis to tap into individual creativity and passion for different things. Our "system" should emphasize the importance of exploration, inquiry, excavation of something that may be buried or of something that has not even been found yet... Transforming current ideas and developing new ones. This should begin from the earliest years, and it seems as if a child's mind is the most curious anyway. Let's enhance it. Let's congratulate them for asking questions, encourage it, reward it...

But how to transfer this idea from childhood to adulthood? Is that a valid idea when we are students of life no matter which age? Can there be a combination of structure and creativity? Can one exist within the other?

Is there really a linear model of science, or is it just an idea that some try to cram loopy science into for their own sake?

Justification in Education

For a class in which there are so many diverging views ,and so much nuance to sort through, I am continually impressed at how much I agree with what so many people say. What I mean by that is simply, someone makes a comment, I make a note on how I feel about that comment, and then somebody else says what I was thinking. It really is quite a pleasure to feel that you have come up with an original, thoughtful insight and then have somebody think the same. It leads me to believe that this class will continually and collectively go to higher levels of conversation and I am psyched about it.

There was one comment toward the end of class that kind of caught me off guard and I have been thinking about it this week. The comment was made by Lin Kai and it pertained to “things that don’t need justification.” I interpreted this to mean things that we just do for the pleasure of them and nobody questions why we do them. His example was enjoying a cup of tea at the end of a long day. I contrast things that don’t need justification with our education system, which I feel is constantly being justified; for what reasons I am not certain.

I remember first hearing education justified when I was talking to my dad when I was in eighth grade. I questioned why it mattered if I worked hard, essentially because I perceived that there were not any long-term consequences if I did not. Colleges do not care about a student’s marks in eighth grade, I certainly did not care about my grades or work very much, and so school became something that needed justification, and lacking it I did not care. My dad justified the need to work hard then by saying that the study habits I learned at this early stage would help me to learn later on (which he was correct about, for what its worth). I did not work hard in eighth grade, I often skipped classes, and really did not respect the process.

Then I wanted to know what the point of working hard in high school was to go to college, if in college one just needed to work hard again to get ready for a career or more school. Then you have to work hard in more school, or in your career, so that you can advance. For what? Money, power, status? I became very disillusioned with this system, and I guess that I still am, although I have reconciled myself to it to some extent. My disillusionment stems from the fact that I do not believe that education needs justification, it is a beautiful thing in its own right, but when something is justified it somehow is viewed differently and becomes more negative somehow. Ideas why?

The bright side is that I enjoy my education for what it is. I enjoy reading, learning and memorizing shared subjective ideas and equations, debate, and writing. I don’t always agree with how the system works, but I find that much of the time I enjoy what I am doing so the justification is less necessary. Nonetheless, I think the need to justify actions can be a good barometer for whether one is doing what they want to be doing, in education and elsewhere, and so I appreciate Lin Kai’s thought-provoking comment.

I want to think more about

I want to think more about whether there are important differences between the first steps of these competing scientific methods. I like seriously loopy science. I like it's dynamism. I prefer circles to straight lines. I think they feel more appropriate in an age/society/culture that's basically left teleological/theological thinking behind. And I'm glad that we've ditched/are ditching those ways of making sense of the world.

The thing I still like about "Hypothesis" that I'm not sure I get from "Summary of Observations" is the more active, co-constructive connotation of the verb "hypothesize" versus "summarize." Tonight we accepted some pretty big claims with minimal resistance. There is no such thing as empirical knowledge. No such things as facts. If next week we're talking more about the brain, maybe we can talk about how the brain feels about/deals with living this kind of schizophrenic existence where we can believe that the only proper attitude towards "reality" is radical skepticism about everything that appears to "work," but simultaneously go ahead putting one foot in front of the other, flying in airplanes that we assume won't crash because the high priests of physics have arranged the numbers in such a way that they appear to be infallible.

Do we end up with a new kind of dualism? Does weightless, creative, inquisitive thought spin off into some parallel reality, an anarchic space where the goal is an endless circle of cognitive self-pleasuring? That doesn't sound too bad, but then there's just something a little uncomfortable about this new kind of "mind" being inconveniently housed in the "body" that is our life-world with all its lame, heavy, existing systems and structures. How does transforming thought, or even education, become the "transformation of the world." Should this new spirit of unfettered, purely creative thought feel remotely responsible for dealing with/helping out the existing life-world, or can the world only be a drag on it?

Or is some yet to be articulated vision of "education" that potential point of convergence? Where the übermenschen, reach back to help new generations find their way out of the graveyard of ossified "truths" that can't actually be truths (because there's no such thing), only hypotheses that have forgotten they're just temporarily serviceable hypotheses. How much of the old muck does this require us to muck around in? What does it mean to "transform" rather than simply negate or discard?

transformation rather than negation or new dualism

Here's to 'dynamism." Concerns equally well expressed/appropriate. How to blend "radical skepticism" with "putting one foot in front of the other"? Perhaps along the lines of Writing Descartes? "a new kind of dualism." Not if I can help it. Perhaps instead "mind" comfortably (rather than "inconveniently") housed in the body/world? And therefore both drawing from it and able to alter it? Yes, the ambition being to achieve "some yet to be articulated vision of 'education'" that genuinely contributes to transformation. By reminding ourselves and others that "truths' are not only "temporarily serviceable hypotheses' but also the grist from which we can conceive and so try out new ways of being.

Post new comment