Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Price Tags

Barnes had the luxury to not care about money, and, when it comes to art, he didn't want money to be a barrier to others either. That was the point of creating a school rather than a museum: to help others learn about and appreciate art, not for the price tag, but the qualities of the piece itself. In my paper revision I want to talk about these great names (Van Gogh, Matisse, Renoir etc.) and their even greater price tags. How the media's and art enthusiasts' focus on the monetary worth of the collection, violates some of Barnes key principles, as well as negates the importance of many of the other pieces in the exhibit. This relates back to my prior paper because I focused on a piece with very little historical and artistic importance, but Barnes nonetheless included it.

Notes towards our last session: 12/6/13

PREPARATION:

* each of us will select three passages from Life on the Outside,

and post them on Serendip by Monday night, 12/2 (be sure to include p. #s).

* We will then select the ‘categories’ we want to use to discuss them.

* Hayley will print off the passages, and bring the large sheets

(marked w/ the categories) and tape.

I. SASHA: Welcome everyone, provide nametags, distribute any leftover books

II. HAYLEY: Pass out our passages; give everyone time to read and reflect on the one they got

(suggest the possibility of opening the text and reading what happens before and after your selection--

& feel free to write on this text...)

III. HAYLEY: Get into pairs to describe your passage to one another (if we have enough people @ this point):

say what connections you make to it and what questions you have about it.

IV. SARA: We bringing back the sheet of "power" we made in an earlier class.

We're going to pick some categories from this sheet that describe/summarize the main ideas in our passages.

[SASHA WILL BE THE SCRIBE HERE.]

Tape your passage to the sheet which …

Fits best/describes what’s going on/that your passage is an example of...

possible topics:

* zero-sum game

* code-switching

* the power of love/race/class/gender

* identity/intersectionality

* empowerment/agency

V. SASHA: Get folks to talk about why they put their quotes where they did→

with the aim of complexifying these categories

Something soothing

This is mostly unrelated, but I just love the cadence of the story (you really should listen to the author read it in the first link, or read it aloud to yourself from the second), and any excuse to share it is good enough for me. We spoke a lot about death in two ways today--a dead body in itself, and the legacies we adopt and leave. This story speaks to that slightly, and though it does assume normative time, and only references the binary, I personally love the thought behind it. There is a casual acceptance of beliefs of all kinds that I appreciate. I have thought deeply about my personal beliefs on death, life, the soul, and this story’s harmonizing language resonates with me. Again, not exactly related to class, but hey, who doesn’t love a good short story?

Link to the audio (they talk for a while before she actually reads her story, but it happens towards the beginning):

http://www.radiolab.org/story/298146-trouble-everything/

Link to the text:

http://hannahhartbeat.blogspot.com/2013/06/a-history-of-everything-including-you.html

Feminism is for EVERYONE

Bell Hook's book, Feminism is for Everyone is one of the best books I've read so far. She attempts to give the readers more then one perspective on a topic and applies this thinking to many important topics around feminism. This novel may be another example of "feminism unbound." Hook's attempts to permanently question what is feminism past gender and sex? She broadens the definition of who exactly feminism is protecting and focuses on eliminating the patriarchy instead of focusing on small unrealistic goals. This book has inspired the topic for my next web-event that will be analyzing parenting through a "feminism unbound lens." I would be questioning how parenting would be if it was"unbound."

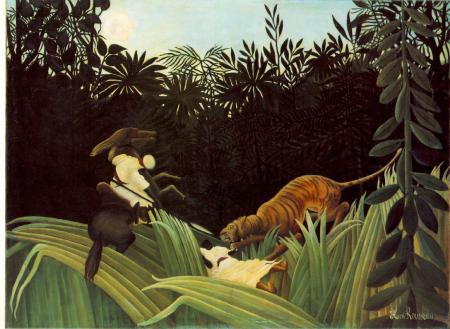

The Attack

What drew me to this painting is primarily the subject matter, and the way the subjects seem to almost glow against the dark background. Two men in white and a ferocious tiger battle desperately deep in some jungle, and there is no way to tell who will win. The piece is “Scout Attacked by a Tiger”, by Henri Rousseau, and it made me think.

The Tree's Solemn Warning

The gallery was full of conversation, dialogue, and dynamic between each and every piece of art. Try putting a bucketful of paintings into one room and keeping them silent. Please, they have so much to say to each other. Compliments, complements, completion and competition. So many voices; it was an exciting hum. But to find one painting, I needed internal dialogue, between the elements within a singular piece. I needed a filter, so I listened to the paintings while keeping a lens of my own poems in mind. A few paintings reached my ears, but it wasn't until I saw a sketch by Glackens that I chose which of my poems I wanted to use. The sketch was of a park with trees and a bunch of people simply milling around. That took my mind to a poem that I wrote, sitting in Maçka Park in Istanbul, Turkey last year on the 24th of October. So I knew that I wanted to use this poem as my filter, though it didn't quite fit this sketch in particular because there was no lamppost. I needed trees and a lamppost. This is the poem:

24th of the Tenth

Do I prefer the black-painted old-fashioned lamppost?

Or the autumn tree, slowly starved and stripped to shame?

Do I prefer the misty beam of yellow light and electricity buzzing, humming, in harmony with the fluttering moths,

or,

the tree’s solemn warning:

“Don’t make me beautiful because you’re lonely,”

as it shakes its balding head.

Gallery Crush

“Would you please turn on the light?” That’s what I first thought when looking at this painting, because the general appearance of this painting is very dark. The left side is darker than the right side, so dark that you can clearly see the tiny cracks on the painting due to it is very old. A woman is bending her back, drawing water from the urn. The light part on her apron makes her apron adds some three-dimension effect, and also makes it seem so heavy. The loose clothe and the creases on it make her clothes seem worn. The white cloth on her head covers her eyes, but it seems that she is looking at the bucket on the floor, tiredly. The light comes from the open door. There stands a woman, with something in her hand. I couldn’t see it clearly. I stepped back, tiptoed, stepped forward, and crouched: no matter what I did, I just couldn’t get what is in her hand. It seems long, probably a broom. There is a little child next to her. Her fingers are thick— she probably do a lot of chores every day. She looks like a servant, not hostess of a poor family, but servant, because the woman at the door dresses the same as her. Everything looks daily: the brooms, the buckets, even the women. Everything seems routine: the women may do it repeatedly, every day.

About Giving Thanks

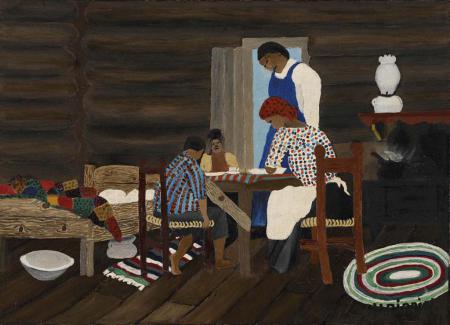

Giving Thanks

That is a small sized picture compared to all the other works hung up on the wall. After walking around the museum several times, it attracted my attention. It’s a portrait of a small wooden house (or room). With one single bed on the left, a table in the middle and several people around, it’s a normal scene. But it has some attractions distinguished from the rest of the museum.

The use of colors is the first thing that captured my eyes: the mainstream is black, dark red, brown and white, repeatedly. But even with these mainly dark colors, my impression for it is still bright. The whiteness is conspicuous---it has a strong sense of presence. The painting is incompatible with the other ones on the same wall, the contrast of color brought up a brand-new feel, and even it’s an old art piece talking about time few decades ago. The whiteness draws clear outlines in this painting: the pillows, the plates, the apron of the woman, and in the texture of the carpet. However, the whiteness did not have a delightful feeling; it’s just neat, or even dazzling. The only color I like is the sky outside their door: pure blue, without even a piece of cloud or a glance of horizon. I wondered that this might be the painter’s expression of life: the pure beauty outside be the dream and the inside darkness is the reality. The sky is also the light source of the room because there’s no lights inside the room.

The Girl with the Golden Eyes

Flowing. Floating. Drifting. Orange and dark blue run by, through, into each other. Like the warm ocean current from the equator meets the cold one from Arctic, crushing, fusing, solving, dissolving, creating home for diverse beautiful oceanic creatures. A man in dark clothes stands still in the waves.

Barnes Foundation, with its modern, luxurious outlook, seemed just another museum to me. I expected the inside display to be one painting per wall, so that the artworks could be given sacred majesty and be enshrined and worshiped. On the contrary, paintings are placed close together, so close that, in order to keep them from fighting for space, they are separated by huge keys, carved fences, and spearheads. Now that the artworks exist in peace and harmony, they talk and dance with each other. Two pieces of the same painter share similarity or symmetry; a huge portrait of an elderly man surrounded by smaller portraits of children like an old man surrounded by his grandchildren; an ancient African painting looks like a 19th century work; a painting and a sculpture have astonishingly similar patterns.

La Tasse de Chocolat

As I approached the chic new building that was created to hold the vast quantity of art pieces that Barnes had collected in his life, I was expecting the traditional layout of a museum, with artwork lining the walls with plaques underneath yielding descriptions of the works and their creators. However I was overwhelmed by the vast amount of artwork pieced together into a playful collage that led from room to room with hundreds of paintings, works of iron, sketches, and sculptures, all intentionally placed into a specific pattern, allowing for pieces of art to play off of one another, making each work better than it would be if it were displayed on its own. As I toured along the walls and walls of art, I kept finding myself drawn to the soft shades and strokes of the Pierre-Auguste Renoir pieces, I love the impressionist era, and Renoir pieces seemed to line the walls.

As I approached the chic new building that was created to hold the vast quantity of art pieces that Barnes had collected in his life, I was expecting the traditional layout of a museum, with artwork lining the walls with plaques underneath yielding descriptions of the works and their creators. However I was overwhelmed by the vast amount of artwork pieced together into a playful collage that led from room to room with hundreds of paintings, works of iron, sketches, and sculptures, all intentionally placed into a specific pattern, allowing for pieces of art to play off of one another, making each work better than it would be if it were displayed on its own. As I toured along the walls and walls of art, I kept finding myself drawn to the soft shades and strokes of the Pierre-Auguste Renoir pieces, I love the impressionist era, and Renoir pieces seemed to line the walls.