Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

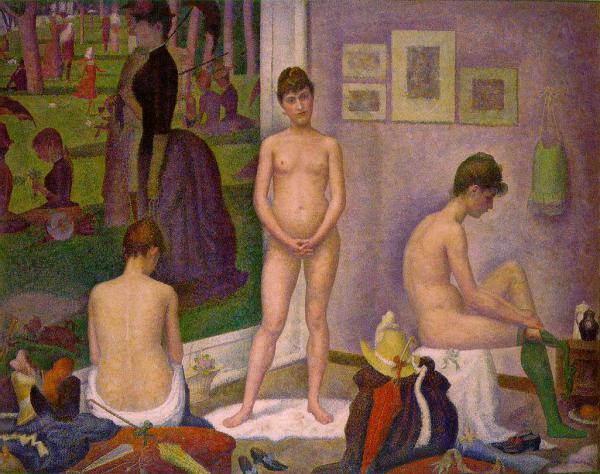

Seurat's Models

To me, one of the most intriguing paintings in the Barnes Foundation was Seurat’s Models. I was told, in AP Euro, to always first look for geometric patterns within the artwork when examining art. So, I did that, and came away with: the three models in the painting form a triangle. But that’s all. The rest of what I took away was much more conceptual and based mostly on ideas rather than strict form.

The pose of the middle model, legs spread wide, feet planted firmly on the floor, and hands clasped in front, suggests, to me, self confidence. She looks very openly at the viewer- “Yes, I’m here, what of it?” With her head tilted a little to the side and steadfast gaze, it’s almost like she’s daring you to ask her what she’s doing there. The other two models are turned away. Their body language does not suggest shyness, but they’re not as open as the middle model is. Also, we can’t see their eyes, whereas the eyes of the middle model seem to follow you no matter where you stand in front of the painting.

The Ribalds Daumier

The lack of features in the face of the woman in the forefront of this painting is what I first noticed. I kept looking because of the rough indents in her face alluded to what she might look like, they reminded me of festive movement. I think one possible reason for the lack of facial detail is that she is in movement. She appears to be either dancing or greeting someone. There is a second woman next to her that has her arm raised with her fingers spread. This pose could be one of greeting or a dance movement. The woman in the forefront further supports the idea that it is a greeting by looking at the general direction of the waving hand. She is also holding an object that resembles a book; it looks like she has stuck her thumb inside of a page to keep it open. This implies that she had recently stopped reading in order to wave at someone or dance.

The Incarnation

Standing next to a couple at the Barnes Foundation on Friday, I overheard the woman state that Albert Barnes was an artist. Each wall is organized with paintings, frames, knives, and hinges hung on top burlap and furniture below. This was his work of art as he paid a great deal of attention to the ways the pieces spoke and contrasted with one another. There is a certain balance and symmetry to each wall and Barnes tends to place paintings together with similar tone and hue. I also noticed that there were rooms and sections of the museum where paintings were clumped together based on whether they were portrait or landscape.

Sign for a Locksmith

Sign for a Locksmith

To say I am not an artistic person is not completely accurate; I am not a two dimensionally artistic person. I can appreciate art and the talent that it takes to create beautiful paintings, but I rarely have intense emotional connections to images of things and people I do not know. Three-dimensional art, however, makes sense to me. It has a purpose, functional or not, and, having taken 3D art all four years of high school and worked with a variety of mediums, I can see how much work went into each individual element of an object. Because of this distinction I generally find art galleries and museums to be painful. I have to force myself to think about the paintings. I do not see a painting and just know this is the emotion I am meant to be feeling right now or the artist’s use of light is to symbolize the dreariness in the subject’s heart. But I can see a sculpture and know the artist must have spent ages getting those angles right or these elements were a bitch to assemble. This is what made the Barnes Foundation so refreshing: it was not a typical art museum. I could look at the Renoirs and Cézannes and then look up and see hinges and ladles and one giant key.

Speaking with Art

Stepping into the Barnes Foundation was nothing short of majestic. I had been looking forward to going to the Barnes for several months; even Cordelia knew how excited I was. Some people say that when you build up something you haven’t experienced in your head, all that happens is that you get disappointed. Fortunately, while I did build the museum up in my head onto a lofty pedestal, “disappointed” was definitely a word I would never use to describe my time at the Barnes Foundation.

Stepping into the Barnes Foundation was nothing short of majestic. I had been looking forward to going to the Barnes for several months; even Cordelia knew how excited I was. Some people say that when you build up something you haven’t experienced in your head, all that happens is that you get disappointed. Fortunately, while I did build the museum up in my head onto a lofty pedestal, “disappointed” was definitely a word I would never use to describe my time at the Barnes Foundation.

I chose Le linge, or The Laundry, painted by Édouard Manet in 1875 to study in isolation. The painting is of a woman and a child doing the laundry in a garden. Impressionism is one of my favorite periods of art – to be honest, it’s probably everyone’s favorite period of art. There’s something about the soft, quick brushstrokes of this art period that makes me feel at ease. The painting of a woman and (possibly) her child creates a personal atmosphere, rendering it a domestic scene typical of many paintings during this time.

the postman

The eyes. He is staring at you, at every angle. I was attracted at the first glance of “The post man” by Van Gogh. People will be swamped into his deep eyes with complex emotions. I couldn’t resist sticking to that pair of eyes. At first, I feel the sadness, and then I find a sense of pride and even arrogance inside. (Maybe because he stares at me directly as the way I stare at him for a long time.) The whole painting is full of lines and mixed colors. His mustaches are twisted, curly and dark; his face is not that clear with various tones of colors combined (warm color such as orange, red and pink, cold colors such as cyan, gray and dark green); however, in sharp contrast, his eyes are so clear. The blue eyes are breathtakingly beautiful like a holy lake surrounded by the messed forest. It has a magic power that I can’t move away my sight. After a long time, I find that it is not sad, not arrogant, but innocent. No. It is some kind of innocent grief that being expressed from his eyes.

The Novice

This weekend I had the good luck to pick the painting that simply does not exist outside of one small side-gallery full of Picassos and Manets. In other words, “The Novice” by Afro Basaldella is incredibly obscure (it was not listed on the Barnes website or even in the artist’s own archive), so I am, unfortunately, required to describe a complex piece without even the luxury of a picture.

Let’s begin this nigh impossible task: The background is two different shades of blue-green. Divided by a red-brown line that bends sharply in the middle of the canvas. Below the line, there is a light greenish color, while above the line the darker blue-green dominates. Littering the entire background are barely noticeable hints of red, like a paint brush dipped in nearly-dry paint and dragged lightly over a few patches of the canvas. From afar, they disappear into the blue-green. In the middle of the picture is a figure of a boy. The figure begins at the bottom with two lines (of the same red-brown color from earlier), which taper slightly inwards to form the neck and sitting on top of this neck is an ovular face. A trapezoidal nose sits in the middle of the face while on the left side of the nose is a black pupil-ed eye with an iris of the same color as the lines. Even further to the left lies a pink ear jutting out from the side of the head. Neither of these features are mirrored on the right side of the face.

Right to Silence

I found the conversation on Tuesday interesting about the right to silence and to know what others are thinking. I was uncomfortable with the idea that someone else has the right to know what I’m thinking. I think that in an academic environment there is an obligation to speak but I don’t think we ever should feel that we don’t have the right to be silent. At the same time I think that silence can become a crutch. There is a difference between choosing to be silent as a way to express yourself or your ideas and being silent because its convenient or you don’t want to speak. I think that by attributing such positive things to being silent that it creates an environment where people may just not speak. I still believe and appreciate the right to be silent but I think that it is better to express yourself and speak up if you are able and it is the right thing to do. I still don’t think that anyone has a right to my thoughts but I have an obligation to speak.