Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

30 Minutes with Matisse

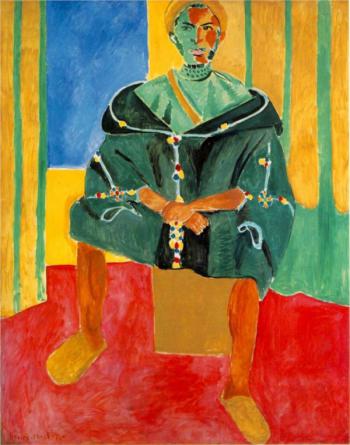

Within the beautiful modern architecture of the Barnes Foundation, hundreds of insanely famous artists and masterpieces are showcased. After a few hours of being overwhelmed by the different rooms, I decided to sit down for a bit. I rested on a bench in front of a giant painting by Henri Matisse. I stared at the work, not especially liking what I saw. As I sat there, however, the piece grew on me, and before I knew it, thirty minutes had passed.

Some things I noticed from looking at the painting:

The colors are very vibrant. The contrasting dark green versus pink versus teal drew my attention to it in the first place. When I first glanced at it, it appeared gaudy, clown-like, and like a cry for attention, but I soon noticed the smaller details, like the shading on the man’s face, which showed true skill.

Mourning

Something that is on my mind since our discussion in class (as well as with the Butler reading) is the nature of mourning. Mourning is not an act that is set to accomplish anything, but rather a kind of reflection and attempt at closure for the sake of oneself. In a way, mourning is more centered on those who mourn rather than the person or object that is being mourned. We mourn, not because of the death or departure of who/what we mourn, but because we have lost something that can no longer provide for us. People never truly mourn for the sake other people or objects. People mourn for the sake of themselves.

right to vulnerability?

I thought Tuesday’s discussion about whether or not a person has a right to know what I am thinking in the classroom was very interesting. Personally, I do not think that anyone has right to my thoughts. There certainly is a requirement to speak for participation reasons but is a requirement the same as a right? My first Serendip web event focused on silence in the classroom and a possible strategy to overcome that silence but one of the essays I read for this web event talked about the vulnerability to silence.

(Here is the reference made in my web event)

In the essay, "The Silenced Dialogue: Power and Pedagogy in Educating Other People's Children,” Lisa Deplit claims that speaking in class should make us “vulnerable enough to allow the world to turn upside down in order to allow the realities of other to edge themselves into our consciousness” (297).

Re-reading my web event with this new context of a right to hear thoughts made me wonder if anyone has a right to my vulnerability. It may not be the intention but it can be a consequence. Forced speech could become forced vulnerability. This may or may not be the thought process of the people who maintain their right to silence but I thought it was an interesting connection.

on mourning, temporality

"in mourning, one discovers horizons, banisters, firmaments, and foundations of life so taken for granted that they were mostly unknown until they were shaken. A mourning being also learns a new temporality...the future is unmoored from parts of the past, thus puncturing conceits of linearity with a different way of living time." (p. 100).

Change is inevitable. A constant. Everything moves. Everything falters? Or does it melt?

Dehumanization

I'm really intrigued by the points Butler makes in this chapter. The train of grief -> vulnerability -> dehumanization really caught my interest, and while Butler relates it to intersectional cuases and the view of Third World women's stuggles and efforts, I personally thought of the 'Save Second Base' campaign. While of a completely different scale, it shows a different angle of the same - women are put at risk until a third party takes advantage of their situation. They are degraded to the means to an end, in Afghanistan as a 'liberation movement' to put US troops in the Middle East, and on United States soil as a pair of breasts meant to be saved for the enjoyment of others and to sell pick and white trinkets with ribbons. The failure of such movements can be seen through Angelina Jolie's double mastectomy - faced with such a high chance of breast cancer, she removesthe cause and is chided for not thinking of her appearence. Butler is right: Americans have been desensitized to death. Death happens; it is normal and unavoidable and can only be put off so often, and is put off minds because of its unpleasantness. But to imply the importance of a segment of tissue over a human life demonstrates another failure in our culture.

[cancer survivor and BoingBoing editor Xeni Jardin reporting on 'Pinktober']

'how feminism became capitalism's handmaiden"

My daughter just sent me this article, written by Nancy Fraser and publishd in The Guardian (Oct. 13, 2013):

How feminism became capitalism's handmaiden--and how to reclaim it. I thought, given our recent discussion with Heidi Hartmann, and our more recent one "with" Wendy Brown about the end of the feminist revolution, it might capture your interest. Here's a taste: "We should break the spurious link between our critique of the family wage and flexible capitalism by militating for a form of life that de-centres waged work and valorises unwaged activities, including – but not only – carework.’"